GAIA is expanding from its North Atlantic right whale origins to support endangered species monitoring across all NOAA Fisheries science centers. This multi-species expansion demonstrates the platform's strategic importance to NOAA's conservation mission.

INTRODUCTION – WHY THIS MATTERS

In my experience, the most heartbreaking sound in marine conservation is the hydrophone recording of a North Atlantic right whale call, suddenly cut short by the unmistakable noise of a ship’s propeller. I first heard such a recording in 2019 during a NOAA Fisheries briefing in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The room fell silent. We were listening to the death of one of the last 400 individuals of a species that once numbered in the tens of thousands.

What I’ve found is that most people—including many conservation professionals—still imagine whale monitoring as it was portrayed in 1990s documentaries: a biologist in a yellow foul-weather jacket, leaning out of a twin-engine aircraft, binoculars pressed against a vibrating window, shouting “Whale at 2 o’clock!” to a data recorder clutching a clipboard. That method, known as aerial survey, has served us honorably for decades. It has produced the abundance estimates, migration maps, and mortality data that underpin every major whale conservation policy in existence.

But it is no longer sufficient.

The North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) population now hovers between 340 and 350 individuals—so few that every single death is a measurable setback to species recovery. Ship strikes and fishing gear entanglement account for the vast majority of diagnosed mortalities. To save this species, we must know where the whales are, not just where we happened to fly an airplane last Tuesday. We must know in real time, across the entire western Atlantic, from the calving grounds off Florida and Georgia to the foraging habitats in the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy.

This is impossible with aircraft. It is impossible with ships. It is impossible with the most sophisticated network of ocean buoys and passive acoustic monitors ever deployed.

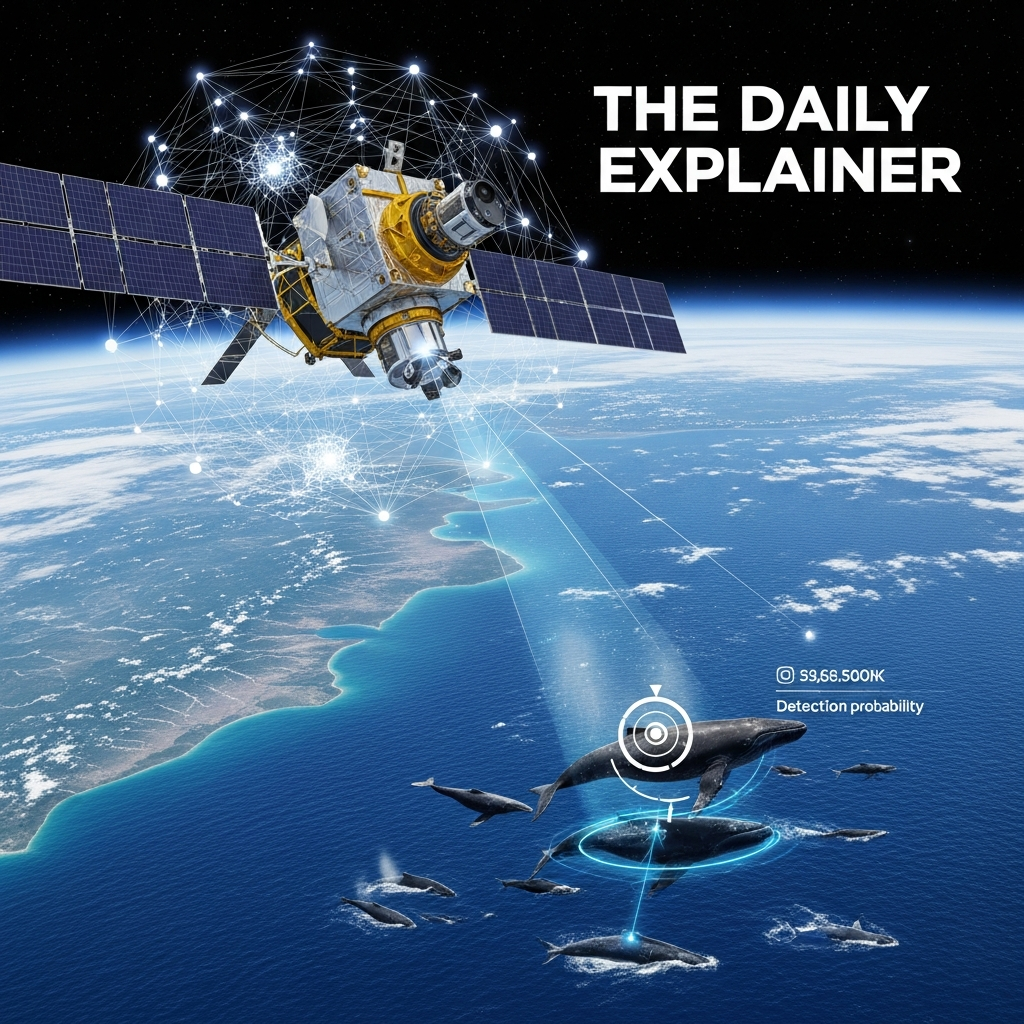

But it is not impossible with satellites.

The Geospatial Artificial Intelligence for Animals (GAIA) initiative, led by NOAA Fisheries in partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey, Microsoft AI for Good, the Naval Research Laboratory, and other collaborators, represents the most ambitious attempt ever undertaken to detect and monitor endangered whale species from space . By combining very high resolution (VHR) satellite imagery with advanced machine learning algorithms and cloud-based geospatial analysis, GAIA is building a system that can survey tens of thousands of square kilometers of ocean in a single imaging pass—an area that would require weeks or months to cover with traditional aircraft.

This is not a futuristic concept. As of January 2026, GAIA version 0.1 is operational. The Cape Cod Bay case study, comparing satellite-based detections with independent aerial survey data collected by the Center for Coastal Studies between 2021 and 2024, is actively validating the accuracy and reliability of this approach . The platform is expanding to support multiple species across all NOAA Fisheries science centers, from Rice’s whales in the Gulf of America to Southern Resident killer whales in the Salish Sea, from beluga whales in Cook Inlet to green sea turtles and Hawaiian monk seals in the French Frigate Shoals .

This article is your comprehensive guide to understanding how satellite AI is rewriting the rules of whale conservation. Whether you are a curious beginner encountering this technology for the first time or a seasoned marine mammal scientist seeking a detailed update on the 2026 landscape, I have structured this guide to meet you where you are. We will cover the fundamental physics of satellite imaging, the intricate machine learning pipelines that transform pixels into detections, the rigorous validation protocols that distinguish science from hype, and the profound conservation implications of a world where we can finally see endangered whales from the ultimate vantage point: space.

BACKGROUND / CONTEXT

The Problem That Aircraft Cannot Solve

To appreciate why satellite AI represents such a revolutionary leap, we must first understand the irreducible limitations of traditional whale monitoring methods. These are not trivial inconveniences; they are fundamental constraints that have shaped—and limited—marine mammal conservation for half a century.

Aerial Surveys: The gold standard for abundance estimation and distribution mapping. A twin-engine aircraft flies at 300–500 meters altitude along predetermined transect lines. Two or three observers scan the water surface through bubble windows, recording each whale sighting with GPS coordinates, group size, and behavioral state. A data recorder logs everything on a laptop or paper datasheet.

The limitations are severe. Aircraft have limited range; they must return to base for refueling. Weather constraints are absolute; low clouds, high winds, or poor visibility cancel missions. Observer fatigue is real; after four hours of scanning featureless ocean, human detection probability declines measurably. Most critically, aircraft cannot be everywhere at once. The North Atlantic right whale’s range spans the entire U.S. and Canadian eastern seaboard—thousands of linear kilometers. No nation possesses the aircraft fleet, pilot hours, or budget to survey this area more than a few times per year.

Shipboard Surveys: Valuable for photo-identification, biopsy sampling, and behavioral observation. Ships can carry heavier instrumentation, remain on station longer, and operate in conditions that ground aircraft. But ships are slow, expensive (exceeding $50,000 USD per day for large research vessels), and limited in spatial coverage. A ship transiting at 10 knots covers approximately 450 square kilometers per day—a tiny fraction of the North Atlantic right whale’s critical habitat.

Passive Acoustic Monitoring: Hydrophone arrays detect whale calls, providing 24/7 presence data regardless of weather or daylight. Acoustic networks like the U.S. Northeast Passive Acoustic Network now cover substantial portions of right whale habitat. However, acoustics detect vocalizing whales only. A silent whale is an invisible whale. Moreover, acoustic localization is imprecise; we know a whale is somewhere within a several-kilometer radius of the hydrophone, but not exactly where—information essential for issuing dynamic management measures like vessel speed reduction zones.

The Common Thread: Every traditional method trades spatial coverage against temporal resolution. Aircraft provide high-resolution snapshots of tiny areas. Acoustics provide continuous data from fixed points. Ships provide rich behavioral data from limited tracks. None can deliver what conservation urgently requires: frequent, systematic, high-resolution surveillance of entire ocean basins.

The Satellite Revolution

The idea of detecting whales from space is not new. As early as the 2000s, researchers experimented with commercial satellite imagery, hoping to spot the dark, elongated shapes of whales against the bright, textured background of ocean surface. The results were tantalizing but inconsistent. Image resolution was too coarse. Atmospheric interference degraded quality. Manual review of thousands of square kilometers was impossibly labor-intensive. Most critically, no one had yet developed the machine learning tools necessary to automate detection at scale.

Two technological trajectories converged to change this equation.

First, satellite imaging advanced. Very high resolution commercial satellites—Maxar’s WorldView-3, WorldView-2, GeoEye—now deliver panchromatic imagery at 0.31-meter resolution . At this resolution, a 15-meter adult North Atlantic right whale occupies approximately 50 pixels in length and 10–15 pixels in width. The animal becomes not merely detectable but morphologically distinguishable: the broad back, the absence of a dorsal fin, the characteristic V-shaped blowhole exhalation—all resolvable by trained human experts and, increasingly, by well-designed computer vision algorithms.

Second, artificial intelligence matured. The deep learning revolution that transformed facial recognition, autonomous vehicles, and medical imaging reached marine mammal science. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and, more recently, vision transformer architectures demonstrated remarkable capability in detecting small, cryptic objects in complex, noisy imagery. Microsoft AI for Good, a philanthropic initiative applying machine learning to humanitarian and environmental challenges, recognized that whale detection from satellite imagery represented a tractable computer vision problem with profound conservation implications .

In 2020, a landmark paper titled “A Biologist’s Guide to the Galaxy” laid the conceptual foundation for what would become GAIA. Written by marine biologists who had become unlikely experts in satellite remote sensing, the paper systematically outlined the potential and challenges of using VHR satellite imagery to detect marine animals—and issued an urgent call for a coordinated, multi-institutional effort to build an automated detection system .

Five years later, GAIA is the answer to that call.

The State of Play in January 2026

As of this writing, GAIA version 0.1 is deployed and operational. The platform is a secure, cloud-based application that enables expert annotation and validation of VHR satellite imagery for whale detection . Its first comprehensive case study focuses on Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts—one of the most intensively studied North Atlantic right whale habitats in the world. The GAIA team is systematically comparing satellite-based detections against independent aerial survey data collected by the Center for Coastal Studies from 2021 to 2024, covering more than 50,000 square kilometers of imagery .

The initiative has secured access to U.S. government contracts through the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and the National Reconnaissance Office, distributed by the U.S. Geological Survey with support from the Civil Applications Committee . This unprecedented partnership between civilian conservation science and the national security space enterprise has enabled targeted image collection (known as “tasking”) over seasonal whale aggregations—a level of access that was unimaginable just a decade ago.

The expansion roadmap is aggressive. Beyond North Atlantic right whales, GAIA is already supporting image collection for Cook Inlet beluga whales (Alaska), Rice’s whales (Gulf of America), Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles (French Frigate Shoals), humpback, blue, and gray whales (Gulf of the Farallones), and Southern Resident killer whales (San Juan Islands and Juan de Fuca Strait) . Version 0.2, currently in development, will add support for multiple simultaneous annotation projects, streamlined API-based image loading, expanded sensor compatibility (WorldView-2, GeoEye), and CSV export functionality for validated detections .

We are no longer asking whether satellite AI can detect whales. We are now asking how accurately, how reliably, and how scalably—and we are building the tools to deliver the answer.

KEY CONCEPTS DEFINED

Before we proceed further, we must establish a shared vocabulary. The intersection of satellite remote sensing, machine learning, and marine mammal conservation has generated considerable terminological confusion. Precise language is essential for understanding both the capabilities and limitations of this emerging technology.

Very High Resolution (VHR) Satellite Imagery: Commercial satellite imagery with spatial resolution better than 1 meter. GAIA currently operates primarily on WorldView-3 imagery at 0.31-meter panchromatic resolution . At this resolution, individual adult whales are resolvable as discrete objects. Lower-resolution imagery (Landsat, Sentinel-2, MODIS) is valuable for oceanographic features (sea surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration) but insufficient for direct whale detection.

Tasked vs. Archival Imagery: A distinction fundamental to GAIA’s operational model. Archival imagery consists of satellite images collected in the past for other purposes—commercial mapping, defense intelligence, agricultural monitoring—and subsequently stored in commercial or government archives. Tasked imagery is collected upon request, over specific locations and time periods specified by the GAIA team . Tasking enables coordination with known whale aggregation seasons and, crucially, temporal overlap with validation data from aerial surveys. It is vastly more expensive than archival access but essential for building robust training datasets.

Panchromatic vs. Multispectral: Panchromatic sensors capture intensity across a broad range of visible wavelengths, producing black-and-white imagery at the sensor’s maximum spatial resolution. Multispectral sensors capture specific wavelength bands (red, green, blue, near-infrared) at coarser resolution. GAIA’s detection workflow primarily utilizes panchromatic imagery for its superior spatial resolution, with multispectral bands providing supplementary information for environmental context and potential species discrimination.

Interesting Points: A crucial concept in GAIA’s semi-automated detection pipeline. Microsoft AI for Good’s prototype tool identifies “interesting points”—small areas of pixels whose spectral signature differs from the surrounding water and whose size is consistent with that of a whale . This algorithm does not purport to detect whales definitively; it flags candidate locations for human expert review. The distinction between automated detection and automated candidate generation is philosophically important and often misunderstood.

Training Dataset: The foundational resource for any supervised machine learning application. A training dataset consists of input examples (satellite image chips) paired with correct output labels (bounding boxes around whales, species identifications, confidence ratings). The GAIA team is building a robust, well-annotated training dataset through a rigorous protocol: three independent subject matter experts annotate each image; a final validation step reconciles discrepancies and ensures consensus; all annotation data is stored in a SpatiaLite database with full geospatial querying capability . The quality of this dataset directly determines the performance ceiling of all subsequent machine learning models.

Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (COG): A file format standard for storing georeferenced raster imagery that enables efficient access via HTTP range requests. GAIA’s cloud application displays preprocessed Maxar level 1B imagery as COGs, allowing users to adjust brightness and contrast directly in the browser interface without downloading massive full-resolution files . This technical infrastructure, invisible to end users, is essential for enabling collaborative annotation across geographically distributed expert teams.

False Positive / False Negative: In satellite whale detection, a false positive occurs when the algorithm or human annotator identifies a whale-like object (wave, whitecap, debris, vessel wake) as a whale. A false negative occurs when an actual whale present in the image is not detected. The trade-off between these error types is adjustable via confidence thresholds. For conservation applications, the acceptable balance depends on the intended use: dynamic vessel management may tolerate false positives (better to inconvenience a ship captain than to strike a whale) but cannot tolerate false negatives; population estimation requires unbiased detection probability; presence/absence mapping occupies an intermediate position.

Preprocessing Workflow: The sequence of image corrections applied before human or machine analysis. GAIA’s preprocessing pipeline includes geometric corrections (aligning imagery to precise ground coordinates), noise reduction, and contrast enhancements to improve visual clarity . These steps are not merely cosmetic; they directly influence detection performance. A poorly preprocessed image may render visible whales invisible; an optimally preprocessed image may reveal whales that were initially undetectable.

Spatial-Temporal Footprint: The volume of ocean area multiplied by time that a monitoring system can effectively survey. Traditional aerial surveys achieve moderate spatial resolution over limited area for brief periods. GAIA’s aspiration is a large spatial-temporal footprint: routine, repeated, synoptic surveillance of vast ocean regions . This is the metric that ultimately determines conservation value.

Dynamic Management: Regulatory measures that are triggered or modified based on near-real-time species occurrence data. For North Atlantic right whales, dynamic management includes voluntary and mandatory vessel speed reduction zones (commonly called “slow zones”) established when whales are detected in an area. Satellite AI’s potential to provide frequent, broad-scale occurrence data could transform dynamic management from a reactive to a predictive enterprise.

HOW IT WORKS (STEP-BY-STEP BREAKDOWN)

Satellite AI whale detection is not a single technology but an integrated workflow spanning satellite tasking, image acquisition, preprocessing, candidate generation, human annotation, machine learning, validation, and operational deployment. Based on detailed technical documentation from NOAA Fisheries and the GAIA team, I have broken this workflow into nine discrete stages .

STEP 1: Strategic Tasking and Collection Planning

Every satellite image begins with a question. Where are the whales likely to be? When will atmospheric conditions be favorable? Which satellite sensors are available for tasking?

The GAIA team commissions new collection of satellite imagery through partnerships with the U.S. Geological Survey and, via the Civil Applications Committee, access to National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and National Reconnaissance Office contracts . This is not an automated process; it requires deliberate prioritization of conservation objectives against finite satellite tasking capacity.

Tasking decisions balance multiple factors:

- Phenology: When are North Atlantic right whales predictably present in Cape Cod Bay? When do Cook Inlet belugas congregate in specific glacial fjords?

- Validation requirements: For the Cape Cod Bay case study, imagery was tasked to coincide temporally with Center for Coastal Studies aerial surveys, enabling direct comparison between satellite and aircraft detections .

- Environmental conditions: Low cloud cover, minimal sea state, and optimal sun angle maximize detection probability.

- Regional priorities: Under the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing, GAIA allocates tasking capacity across NOAA Fisheries science centers to support their priority species and habitats .

STEP 2: Image Acquisition and Ingestion

Once tasked, commercial satellite operators (primarily Maxar for WorldView-3) acquire the imagery and deliver it to NOAA. The raw data arrives as very high resolution panchromatic and multispectral scenes, each covering approximately 100–200 square kilometers, georeferenced to Earth coordinates with sub-meter precision.

The GAIA team has developed a flexible codebase that automates the retrieval of satellite imagery from multiple repositories, including USGS Earth Explorer. This system streamlines access to vast archives of VHR imagery, enabling efficient search, filtering, and download based on location, date, and sensor type.

For the Cape Cod Bay case study alone, the project has covered more than 50,000 square kilometers of imagery—an area approximately the size of Costa Rica.

STEP 3: Preprocessing and Image Optimization

Raw satellite imagery is not ready for human or machine analysis. It contains geometric distortions, sensor noise, variable illumination, and atmospheric interference.

GAIA’s specialized preprocessing workflow applies several corrections :

Geometric correction: Aligning the imagery to precise ground control points, ensuring that a pixel’s coordinates correspond accurately to real-world latitude and longitude. This is essential for subsequent integration with other geospatial data layers (aerial survey tracks, vessel traffic patterns, critical habitat boundaries).

Noise reduction: Removing or suppressing sensor artifacts and random pixel-level variation that could be mistaken for biological targets.

Contrast enhancement: Adjusting the image histogram to maximize visual differentiation between potential whales and the background ocean. A whale’s dark back against the bright sea surface is a subtle contrast; optimal enhancement can make the difference between detection and missed sighting.

The output of this stage is a Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (COG)—a file format that enables efficient streaming and visualization in web-based applications without requiring full-file download .

STEP 4: Automated Candidate Generation (Microsoft AI for Good Prototype)

A trained human expert scanning 50,000 square kilometers of satellite imagery at high magnification would require months. This is not operationally feasible.

To accelerate the process, GAIA incorporates the Microsoft AI for Good prototype tool, WHALE—a semi-automated, cloud-based application designed to streamline annotation . This tool analyzes preprocessed imagery and identifies “interesting points”: localized areas where a cluster of pixels exhibits a spectral signature different from surrounding water and whose spatial extent is consistent with a whale.

Importantly, the Microsoft prototype does not claim to detect whales. It detects whale-likeness. It flags candidates for human review, reducing the search space from millions of pixels to hundreds of candidate chips per scene. This human-in-the-loop architecture acknowledges both the current limitations of fully automated detection and the irreplaceable expertise of experienced marine mammal observers.

STEP 5: Expert Annotation and Validation

This is the heart of GAIA’s training data pipeline—and the most labor-intensive stage.

Three independent subject matter experts (SMEs) review each candidate image chip in the GAIA cloud application . The interface presents the preprocessed COG with adjustable brightness and contrast. SMEs draw bounding boxes around confirmed whale detections, assign species identifications (when possible), and rate their confidence level.

The three independent annotations are then compared. Where all three experts agree on the presence and location of a whale, the annotation proceeds to validation. Where discrepancies exist, a final validation step reconciles differences and ensures consensus.

All annotation and validation data are stored in a SpatiaLite database, supporting efficient storage, spatial querying, and retrieval. This database is the foundational asset from which all subsequent machine learning models will be trained.

STEP 6: Machine Learning Model Training

With a sufficiently large, expertly validated training dataset, the GAIA team can begin training supervised machine learning models to automate whale detection.

The technical specifics of GAIA’s current model architecture are not fully public, but the general approach is well-established in computer vision literature. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or vision transformers ingest image chips and learn to map pixel patterns to detection probabilities. The training process iteratively adjusts millions of model parameters to minimize the difference between predicted and actual whale locations.

Critical to this process is the diversity of the training dataset. GAIA’s imagery captures whales across a wide range of:

- Sea states (calm to choppy)

- Lighting conditions (high sun, low sun, haze)

- Water clarity (clear coastal waters, turbid estuarine plumes)

- Surface behaviors (resting, traveling, surface active groups, fluking up dives)

A model trained exclusively on calm, clear, high-contrast images will fail catastrophically when deployed in challenging conditions. GAIA’s explicit strategy of capturing whales across the full spectrum of real-world conditions is essential for developing robust, generalizable detection algorithms .

STEP 7: Model Validation and Performance Assessment

A trained model’s predictions must be rigorously evaluated against independent test data—imagery that was not used during training and for which the true whale locations are known (via expert annotation).

Standard performance metrics include:

Precision: Of all the objects the model flagged as whales, what proportion were actually whales? Low precision means many false positives, overwhelming users with irrelevant alerts.

Recall (Sensitivity): Of all the whales actually present in the imagery, what proportion did the model successfully detect? Low recall means missed whales—potentially catastrophic for conservation applications.

F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both error types.

Mean Average Precision (mAP): A more sophisticated metric common in object detection literature, averaging precision across multiple confidence thresholds.

The Cape Cod Bay case study represents GAIA’s first comprehensive validation exercise. By comparing satellite-based detections (both human and machine) against independent aerial survey data, the team can quantify not only the model’s technical performance but its operational utility for real-world conservation decision-making .

STEP 8: Operational Deployment and Dashboard Integration

Once validated, detection outputs must be delivered to end users in accessible, actionable formats.

GAIA version 0.1 provides a secure cloud application with an intuitive annotation interface. Future versions (0.2 and beyond) will expand to support multiple simultaneous projects, streamlined image loading via API, and—critically—easy export of validated detections as CSV files .

This last capability is deceptively important. Conservation managers do not need another proprietary visualization platform. They need data they can ingest into their existing workflows: GIS software, statistical analysis environments, and decision support tools. By enabling CSV export, GAIA ensures that its hard-won detections can be analyzed, shared, and acted upon by the full conservation community.

STEP 9: Feedback Loop and Continuous Improvement

The final stage is not an endpoint but a return to the beginning.

As new satellite imagery is acquired, preprocessed, and analyzed—whether by human experts, machine learning models, or the integrated human-AI pipeline—the resulting detections (and non-detections) become new training data. The model is retrained, performance improves, and the system becomes progressively more capable.

This continuous improvement cycle is characteristic of mature machine learning applications. GAIA version 0.1 detects whales. GAIA version 0.2 will detect them better. GAIA version 1.0 may detect them reliably enough for routine operational deployment across NOAA Fisheries science centers.

The trajectory is clear. The destination is not yet reached, but the path is mapped.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

The importance of satellite AI whale detection extends far beyond technological novelty. This capability directly addresses several of the most intractable challenges in marine mammal conservation.

1. Spatial Coverage at Unprecedented Scale

A single very high resolution satellite image can cover 100–200 square kilometers. A single satellite pass, acquiring multiple contiguous scenes, can cover thousands of square kilometers. A single satellite, operating for a year, can cover millions of square kilometers.

Compare this to aerial survey. NOAA Fisheries’ North Atlantic right whale aerial survey team flies approximately 50,000–60,000 linear kilometers per year—an impressive effort, but one that samples a tiny fraction of the species’ range. Moreover, aircraft are constrained to coastal waters; they cannot safely or legally transit 200 nautical miles offshore. Satellites have no such limitation.

The result is not merely more data. It is fundamentally different data: synoptic, wide-area surveillance that reveals the distribution of whales across entire ocean basins, including remote offshore habitats that are rarely or never sampled by traditional methods.

2. Temporal Frequency and Responsiveness

Satellites pass over the same location repeatedly. WorldView-3, for example, has a revisit time of approximately 1–3 days depending on latitude. A constellation of multiple VHR satellites could achieve daily or even sub-daily revisit frequencies.

This temporal density enables monitoring of dynamic processes that have been essentially invisible to conservation science: How quickly do whales move through an area designated for offshore wind development? Do vessel speed reduction zones actually displace whales, or do whales remain in habitat while vessels slow down? How do right whales respond to prey aggregations that shift hourly with tides and currents?

These are not academic questions. They are operational questions that directly affect the design and effectiveness of conservation measures.

3. Complementarity with Existing Monitoring Methods

Satellite AI does not replace aerial surveys, shipboard observations, or passive acoustics. It complements them—filling the gaps that each method leaves.

Aerial surveys provide high-confidence detection of every whale encountered, with species identification, group size estimation, and behavioral observation. But they cover limited area and are weather-dependent.

Passive acoustics provide continuous presence data regardless of weather or daylight. But they detect only vocalizing whales and provide imprecise localization.

Satellite AI provides broad, synoptic distribution data with precise geolocation. But it cannot reliably estimate group size, confirm species identification in all cases, or observe subsurface behavior.

These methods are not competitors. They are instruments in an expanding orchestra of monitoring capabilities. The conductor—NOAA Fisheries, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and other management authorities—must learn to play them in harmony.

4. Access to Inaccessible Habitats

The Cook Inlet beluga whale is a distinct population segment of beluga whale, listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, with approximately 280–300 individuals remaining. Its habitat includes remote glacial fjords in south-central Alaska, accessible only by boat during brief ice-free windows and effectively never surveyed by aircraft due to extreme weather and mountainous terrain .

Satellites do not care about weather. Satellites do not require airport runways. Satellites do not need to refuel. For species inhabiting the planet’s most inaccessible marine environments—polar belugas, remote island monk seals, deep-diving beaked whales in offshore canyons—satellite AI may represent the only realistic path to systematic monitoring.

5. Scalability Across Species and Ecosystems

GAIA’s current focus on North Atlantic right whales and Cook Inlet belugas is strategic: these are among the most endangered marine mammal populations in U.S. waters, with clear conservation urgency and well-established regulatory frameworks .

But the infrastructure being built—the preprocessing workflows, the annotation platform, the machine learning pipelines, the geospatial databases—is fundamentally species-agnostic. Once GAIA version 0.2 supports multiple simultaneous annotation projects, the same system that detects right whales in Cape Cod Bay can be adapted to detect Rice’s whales in the Gulf of America, Southern Resident killer whales in the Salish Sea, humpback whales in the Gulf of the Farallones, and green sea turtles at French Frigate Shoals .

Further expansion beyond marine mammals is entirely plausible. Large fish aggregations, seabird flocks, marine debris concentrations, harmful algal blooms—any phenomenon detectable at 0.31-meter resolution is a candidate for this analytical architecture.

6. Democratization of Conservation Data

This potential is not yet realized, but it is visible on the horizon.

High-resolution satellite imagery remains expensive. Tasked collection costs thousands of dollars per scene. Not every university laboratory, non-governmental organization, or developing country marine protected area can afford such access.

However, the cost trajectory of satellite remote sensing is downward. More commercial providers are entering the market. Constellations of small satellites are proliferating. Archival imagery, while less targeted than tasked collection, is increasingly available at modest cost or even freely for non-commercial research applications.

GAIA’s commitment to open, collaborative development and its partnerships across NOAA Fisheries science centers and academic institutions are steps toward democratizing access. A future in which any qualified researcher can submit a whale detection query to a GAIA-like platform, receiving validated results within hours, is technologically plausible and conservationally desirable.

SUSTAINABILITY IN THE FUTURE

Where Is Satellite AI Whale Detection Headed in 2026 and Beyond?

GAIA version 0.1 is operational. GAIA version 0.2 is in active development. The roadmap beyond is ambitious and, based on the technical documentation, appears to be organized around five strategic priorities .

Priority 1: Expanding Sensor Compatibility

GAIA version 0.1 currently supports only Maxar WorldView-3 imagery . This is a severe operational constraint. WorldView-3 is a single satellite with finite tasking capacity. If it experiences technical problems, the entire detection pipeline stalls.

Version 0.2 will expand compatibility to include additional high-resolution sensors, specifically WorldView-2 and GeoEye . This enhancement will significantly increase the volume of available imagery and extend detection capability across a wider range of locations and time periods.

Longer-term expansion to include synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites, which image through clouds and darkness, is technologically plausible but methodologically challenging. SAR imagery is fundamentally different from optical imagery; whale-sized objects produce different radar backscatter signatures. Adapting GAIA’s computer vision architecture to SAR would require substantial research and development investment.

Priority 2: Enabling Multi-Project Parallel Operations

GAIA version 0.1 is designed around a single annotation project: Cape Cod Bay North Atlantic right whales . This focused scope was appropriate for initial development and validation.

Version 0.2 will support multiple simultaneous annotation projects . This upgrade enables the platform to process imagery for several research efforts at once, addressing animal detection needs across all NOAA Fisheries science centers in alignment with the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing priorities.

The implications are substantial. A single research team can no longer manage the annotation workload for beluga whales, Rice’s whales, killer whales, humpback whales, monk seals, and sea turtles simultaneously. GAIA must evolve from a single-user tool to a multi-user collaborative platform with project-specific access controls, data segregation, and workflow management.

Priority 3: Streamlining Image Access and Ingestion

Currently, loading new satellite imagery into GAIA requires technical intervention—running code, managing file transfers, updating databases. This is acceptable during development but unsustainable for operational deployment.

Version 0.2 will build a user-friendly interface for accessing image repositories via Application Programming Interface (API) . Scientists will be able to easily load new imagery into their projects from the USGS Earth Explorer repository—no coding required. Each image will be automatically ingested with its relevant metadata and processed through GAIA’s preprocessing pipeline, producing high-quality visualizations ready for annotator review.

This is not merely convenience. It is democratization. When the barrier to entry is a graphical interface rather than a command line, the community of potential GAIA users expands from computational specialists to all NOAA Fisheries scientists and, eventually, to external collaborators and partners.

Priority 4: Enabling Data Export and Interoperability

GAIA’s current value proposition is internal: it helps NOAA scientists generate high-quality training data. But the ultimate value of whale detection data is realized when it leaves GAIA and enters the broader conservation information ecosystem.

Version 0.2 will add easy export of validated whale detections as CSV files . This straightforward capability is strategically vital. Researchers can share results with collaborators, perform additional statistical analyses, incorporate annotated data into their own machine learning workflows, and integrate GAIA detections with vessel traffic data, habitat models, and regulatory decision-support tools.

CSV export transforms GAIA from a standalone application into an interoperable component of a distributed conservation data infrastructure.

Priority 5: Expanding Taxonomic and Geographic Scope

GAIA’s current focus on cetaceans reflects its origins and the urgency of North Atlantic right whale conservation. But the platform’s architecture is broadly applicable.

Under the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing, GAIA is already supporting image collection for:

- Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center: Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles at French Frigate Shoals

- Southeast Fisheries Science Center: Rice’s whales in the Gulf of America

- Southwest Fisheries Science Center: Humpback, blue, and gray whales over the Gulf of the Farallones

- Northwest Fisheries Science Center: Southern Resident killer whales in waters west of the San Juan Islands and the Juan de Fuca Strait

Each new species presents unique detection challenges. Seals are smaller than whales. Sea turtles are smaller still. Killer whales exhibit high-contrast black-and-white coloration unlike right whales’ uniform dark back. Adapting GAIA’s preprocessing workflows, annotation protocols, and machine learning models to this diversity of targets is a multi-year research program.

But the trajectory is unmistakable: from single species to multi-species, from single region to global, from specialized research tool to operational conservation infrastructure.

COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS

Satellite AI whale detection has attracted both uncritical enthusiasm and reflexive skepticism. Based on careful reading of GAIA’s technical documentation and the broader scientific literature, I here address the most persistent misconceptions.

Misconception 1: “Satellites can already detect whales automatically anywhere in the ocean.”

Reality: Absolutely false. Current GAIA capabilities are limited to very high resolution imagery (0.31-meter panchromatic) collected under favorable environmental conditions (low sea state, minimal cloud cover, optimal sun angle) over known whale aggregation areas with extensive validation data. Automated detection algorithms are still under development; the current operational workflow relies on human expert review of algorithm-generated “interesting points.” Reliable, fully automated detection across the global ocean under all conditions remains a research goal, not an operational reality .

Misconception 2: “Satellite detection will replace aerial surveys.”

Reality: No. Aerial surveys and satellite detection provide fundamentally different information. Aerial observers can reliably identify species, estimate group size, assess behavior, photograph individual animals for photo-identification, and biopsy sample for genetic analysis. Satellites currently provide presence/absence data with varying confidence levels and limited ability to discriminate species. The GAIA team explicitly positions satellite detection as complementary to, not a replacement for, traditional survey methods. The Cape Cod Bay case study is designed to validate satellite detection against aerial survey data, not to render aerial surveys obsolete .

Misconception 3: “If a whale is present in satellite imagery, GAIA will detect it.”

Reality: False. Detection probability is conditional on numerous factors. The whale must be at the surface—North Atlantic right whales spend approximately 80–90% of their time submerged. The surface must be visible—cloud cover, haze, and sun glint all obscure whales. The whale’s back must be sufficiently contrast against the background ocean—calm seas produce better contrast than choppy seas. The imagery must be acquired at sufficient resolution and properly preprocessed. GAIA’s own documentation emphasizes that building a robust training dataset requires capturing whales across the full range of real-world conditions precisely because detection is not guaranteed .

Misconception 4: “Satellite AI is too expensive for routine conservation use.”

Reality: This misconception confuses current research and development costs with mature operational costs. It is true that tasked VHR satellite imagery is expensive—thousands of dollars per scene—and that GAIA’s current level of effort (50,000+ square kilometers for the Cape Cod Bay case study) represents a substantial investment enabled by unique interagency partnerships and access to national security space contracts .

However, cost trajectories in satellite remote sensing are downward. More commercial providers, more satellites, and increasing availability of lower-cost archival imagery will reduce acquisition costs. Machine learning efficiency improvements reduce computational costs. As GAIA transitions from research to operations, per-unit costs will decline.

Moreover, cost must be assessed relative to alternatives. A single research vessel day costs $30,000–$50,000 USD. A dedicated aerial survey aircraft costs $2,000–$5,000 per flight hour. Satellite surveillance over thousands of square kilometers, amortized over many applications and many users, may ultimately prove cost-competitive with traditional methods for broad-scale distribution monitoring.

Misconception 5: “Species identification from satellites is impossible.”

Reality: Not impossible, but challenging. Currently, GAIA focuses on detection—is there a whale-like object in this location?—rather than species identification. However, the very high resolution of WorldView-3 and similar sensors (0.31-meter panchromatic) is sufficient to resolve morphological features: the broad, dorsally flat back and absence of dorsal fin characteristic of right whales; the tall, falcate dorsal fin of killer whales; the massive, broad-fluked body of humpback whales.

The limiting factor is not resolution but training data. To build a species classifier, you need thousands of expertly labeled examples of each species under diverse conditions. GAIA is currently accumulating this training data. Species identification from VHR satellite imagery is a solvable computer vision problem; it is a matter of investment and time.

Misconception 6: “GAIA is just Microsoft’s project.”

Reality: No. GAIA is a collaborative initiative led by NOAA Fisheries, with essential contributions from multiple partners: the U.S. Geological Survey (providing access to satellite tasking contracts via the Civil Applications Committee), Microsoft AI for Good (developing the prototype candidate generation tool and cloud application), the Naval Research Laboratory (expertise in remote sensing and image processing), the British Antarctic Survey (developing standardized manual annotation workflows), and academic and non-governmental collaborators.

Microsoft’s contribution is substantial and generously provided through its AI for Good philanthropic program. But GAIA is fundamentally a NOAA-led, multi-institutional public-private partnership. Its success reflects the commitment of many organizations, not one.

Misconception 7: “Once GAIA works for whales, it will immediately work for everything.”

Reality: Transfer learning—adapting a model trained on one task to a related task—is a powerful machine learning technique, but it is not magic. A model trained to detect 15-meter right whales in coastal waters will not reliably detect 2-meter seals in atoll lagoons without substantial retraining on appropriate imagery. The underlying architecture may transfer; the learned weights will not.

GAIA’s expansion strategy appropriately acknowledges this reality. Each new species and habitat requires targeted image collection, expert annotation, and model validation. The platform enables this expansion; it does not automate it.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (2025-2026)

The period from late 2025 through early 2026 has been extraordinarily productive for satellite AI whale detection. Based on the most current NOAA Fisheries documentation (published January 2026), four developments warrant specific attention.

Development 1: GAIA Version 0.1 Deployment (January 2026)

The single most significant recent development is the official deployment of GAIA version 0.1, announced in January 2026. This is not a prototype, not a research tool, not a pilot project. It is an operational cloud application deployed within NOAA’s secure infrastructure, meeting federal security requirements, supporting real annotation work by NOAA scientists and their partners.

Version 0.1 features:

- A cloud-based annotation interface optimized for very high resolution satellite imagery

- Support for three independent subject matter experts per image, with consensus-based validation

- Cloud-optimized GeoTIFF display with adjustable brightness and contrast

- SpatiaLite backend database for efficient storage and spatial querying

- Focused support for the Cape Cod Bay North Atlantic right whale case study

This deployment represents the transition of satellite AI whale detection from academic research to operational conservation infrastructure.

Development 2: Cape Cod Bay Case Study Active Validation (January 2026)

Simultaneously with the version 0.1 deployment, the GAIA team announced that the Cape Cod Bay case study is actively comparing satellite-based detections with independent aerial survey data collected by the Center for Coastal Studies from 2021 to 2024.

This is the first rigorous, large-scale validation of satellite whale detection against established survey methods. The study covers more than 50,000 square kilometers of imagery. It employs two complementary review approaches: targeted, semi-automated review using the Microsoft AI for Good “interesting points” algorithm, and comprehensive visual assessment in ArcGIS Pro, examining the imagery at high resolution across the entire study area, grid cell by grid cell .

The results of this validation study, when published, will provide the conservation community’s first clear-eyed assessment of satellite detection’s accuracy, reliability, and operational utility.

Development 3: Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing Expansion (January 2026)

GAIA’s initial focus on North Atlantic right whales and Cook Inlet belugas reflected the urgent conservation status of these populations and the availability of partners with relevant expertise. In January 2026, NOAA Fisheries announced a major expansion under the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing .

New priority species and regions include:

- Pacific Islands: Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles at French Frigate Shoals

- Southeast: Rice’s whales in the Gulf of America

- Southwest: Humpback, blue, and gray whales in the Gulf of the Farallones

- Northwest: Southern Resident killer whales west of the San Juan Islands and Juan de Fuca Strait

This expansion signals NOAA’s strategic commitment to satellite-based monitoring as a core capability across its science center enterprise, not a specialized research project confined to a single region or species.

Development 4: GAIA Version 0.2 Roadmap Announcement (January 2026)

Concurrent with version 0.1 deployment, the GAIA team published its development roadmap for version 0.2, scheduled for release in 2026 .

Announced features include:

- Support for multiple simultaneous annotation projects

- Streamlined image loading from USGS Earth Explorer via user-friendly API interface

- Expanded sensor compatibility (WorldView-2, GeoEye)

- CSV export of validated detections

- Continued enhancement of preprocessing workflows

This roadmap demonstrates that GAIA is not static. It is a living platform, actively developed in response to user needs and evolving technical capabilities.

SUCCESS STORIES

Success Story 1: The Cape Cod Bay Validation Framework

The most important success story in satellite AI whale detection is not a detection but a methodology.

When the GAIA team initiated the Cape Cod Bay case study, they confronted a classic validation problem: how do you know whether your satellite-based detections are correct if you lack independent truth data? Their solution—comparing satellite detections against the Center for Coastal Studies’ long-term aerial survey dataset—is elegant in conception and rigorous in execution .

This validation framework matters because it establishes a gold standard for all future satellite detection efforts. Any researcher or organization claiming to detect whales from space should be prepared to demonstrate their system’s performance against independently collected, methodologically validated survey data. GAIA has not only accepted this burden of proof; they have embraced it as central to their mission.

Success Story 2: From “Biologist’s Guide” to Operational Platform

The publication of “A Biologist’s Guide to the Galaxy” in 2020 was a call to arms. Five years later, GAIA version 0.1 is the answer.

This trajectory—from conceptual paper to operational platform within half a decade—is remarkable by any standard. It required sustained commitment from NOAA leadership, substantial philanthropic investment from Microsoft, interagency coordination with USGS and the Civil Applications Committee, and the dedicated effort of dozens of scientists, engineers, and program managers.

The conservation community often laments the slow pace of technology adoption. GAIA demonstrates what is possible when urgency meets investment and collaboration.

Success Story 3: Multi-Species Expansion Planning

GAIA’s expansion under the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing is not yet complete, but the planning itself represents a significant achievement.

Each new species and habitat presents unique challenges. Hawaiian monk seals are an order of magnitude smaller than right whales. The Gulf of the Farallones experiences vastly different oceanographic conditions than Cape Cod Bay. Southern Resident killer whales’ black-and-white coloration requires different contrast optimization than right whales’ uniform dark back.

The GAIA team’s proactive engagement with all six NOAA Fisheries science centers, identifying their priority species and monitoring requirements, demonstrates a mature understanding that technology development must be driven by user needs, not developer preferences.

Success Story 4: The Wollombi Parallel (Community eDNA Success)

While not a satellite story, the Wollombi catchment eDNA project in New South Wales, Australia, offers an instructive parallel to GAIA’s citizen science aspirations.

In April 2024, over half of 54 sampling sites across the Wollombi catchment were monitored by local volunteers. Three schools participated in eDNA sample collection. The project detected platypus DNA at 12 locations—double the positive results from the previous sampling round—and rakali (native water rat) DNA at 5 locations.

What makes Wollombi relevant to GAIA is its demonstration that community members, when properly trained and equipped, can collect scientifically valid monitoring data at meaningful scales. GAIA Phase I similarly engaged 250 young citizen scientists across 19 countries, collecting eDNA samples that revealed over 4,000 marine species.

GAIA’s satellite detection work is currently expert-driven. But the platform’s long-term sustainability may depend on expanding the community of annotators, validators, and users beyond NOAA’s science centers. Wollombi and UNESCO eDNA Expeditions demonstrate this is possible.

REAL-LIFE EXAMPLES

Example 1: Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts – The Validation Epicenter

Cape Cod Bay is to North Atlantic right whales what the Serengeti is to African lions: a predictable aggregation area where these endangered animals gather annually to feed on dense zooplankton blooms. It is also one of the most intensively monitored whale habitats on Earth, with the Center for Coastal Studies conducting regular aerial surveys that have accumulated decades of continuous data.

This combination—predictable whale presence and extensive validation data—makes Cape Cod Bay the ideal proving ground for GAIA. The team has tasked satellite imagery to coincide temporally with aerial survey overflights, enabling direct comparison between satellite-based detections and aircraft-based observations.

The results of this comparison, currently under analysis, will determine the trajectory of satellite whale detection for years to come. If GAIA demonstrates high sensitivity (detecting most whales that aerial observers saw) and acceptable precision (few false positives) under Cape Cod Bay conditions, the path to operational deployment across other habitats becomes clear.

Example 2: Cook Inlet, Alaska – The Accessibility Challenge

Cook Inlet beluga whales are one of the most endangered marine mammal populations in U.S. waters, with approximately 280–300 individuals remaining. Their critical habitat includes remote glacial fjords accessible only by boat during brief ice-free windows and effectively never surveyed by aircraft due to extreme weather and mountainous terrain.

This is precisely the type of monitoring challenge that satellite detection is uniquely positioned to address. Aircraft cannot operate reliably in Cook Inlet’s weather. Ships can transit the area but cannot maintain continuous surveillance. Passive acoustic monitoring is limited by ice damage to hydrophones and cannot localize whales precisely.

Satellites face none of these constraints. Cloud cover remains an obstacle (optical sensors cannot see through clouds), but the acquisition window is not limited by airport operating hours, pilot fatigue, or vessel range. GAIA’s expansion to support Cook Inlet belugas represents a genuine conservation innovation, not merely a technological demonstration.

Example 3: French Frigate Shoals, Pacific Islands – Taxonomic Expansion

The French Frigate Shoals, part of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, host the most important green sea turtle nesting aggregation in the Hawaiian archipelago and a significant population of endangered Hawaiian monk seals .

Neither species resembles a whale. Monk seals are approximately 2 meters in length—one-seventh the size of an adult right whale. Green sea turtles are smaller still, and their carapace produces a different spectral signature than mammalian blubber and skin.

GAIA’s expansion to support seal and turtle detection at French Frigate Shoals represents a significant technical challenge. The detection algorithms developed for 15-meter whales in temperate coastal waters will not transfer directly to 2-meter seals in tropical atoll lagoons. New training data must be collected. New preprocessing workflows must be developed. New validation protocols must be designed.

The fact that GAIA is undertaking this challenge demonstrates that satellite AI monitoring is not a one-off experiment but a strategic commitment to building broadly capable conservation infrastructure.

Example 4: Southern Resident Killer Whales, Salish Sea – Cultural Keystone Species

The Southern Resident killer whale population, comprising three pods (J, K, and L pods) that frequent the inland waters of Washington State and British Columbia, is perhaps the most culturally significant marine mammal population in North America. These are the whales that thousands of tourists travel to the San Juan Islands each summer to observe. They are the subject of decades of behavioral research and photo-identification studies. They are also critically endangered, with approximately 75 individuals remaining.

Southern Residents present a different detection challenge than right whales. Their striking black-and-white coloration produces high-contrast imagery—potentially easier to detect than right whales’ uniform dark backs—but their smaller size (adult males reach 6-7 meters, less than half the length of an adult right whale) reduces pixel count at equivalent resolution.

GAIA’s inclusion of Southern Residents in its expansion portfolio acknowledges that satellite monitoring is not only for remote, inaccessible populations. Even well-studied, intensively monitored populations may benefit from synoptic, wide-area surveillance that complements vessel-based photo-identification and acoustic monitoring.

CONCLUSION AND KEY TAKEAWAYS

Satellite AI whale detection has crossed the threshold from research concept to operational conservation tool. GAIA version 0.1 is deployed. The Cape Cod Bay validation case study is active. Expansion to multiple species across all NOAA Fisheries science centers is underway. The February 2026 landscape is fundamentally different from—and vastly more advanced than—the February 2025 landscape.

Yet this is not the endpoint. It is the beginning.

GAIA version 0.1 detects whales with human assistance. GAIA version 0.2 will detect them with less human assistance. GAIA version 1.0 may detect them reliably enough for routine operational deployment. And GAIA version 2.0, 3.0, and beyond will expand to new species, new habitats, new sensors, and new applications that we cannot yet foresee.

The technology is advancing. The question is whether our conservation policies, management frameworks, and funding commitments can keep pace.

Key Takeaways:

1. Satellite AI is not science fiction. GAIA version 0.1 is operational as of January 2026. The platform exists, the partnerships are established, and the validation work is actively underway.

2. Detection is not yet automation. The current GAIA workflow relies on human expert review of algorithm-generated candidate locations. Fully automated detection across all conditions remains a research goal.

3. Validation is the essential foundation. GAIA’s rigorous approach to validation—comparing satellite detections against independent aerial survey data, using three independent expert annotators with consensus reconciliation—sets a gold standard that all future efforts should emulate.

4. Expansion is strategic and deliberate. GAIA’s expansion under the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing, adding new species and habitats across all NOAA Fisheries science centers, demonstrates a mature understanding that technology development must be driven by user needs.

5. Complementarity, not replacement. Satellite detection complements aerial surveys, shipboard observations, and passive acoustics. It does not replace them. The future of marine mammal monitoring is integrated, multi-platform, and methodologically diverse.

6. The window is narrow and urgent. North Atlantic right whales number 340–350 individuals. Cook Inlet belugas number 280–300 individuals. Southern Resident killer whales number approximately 75 individuals. These populations cannot wait for perfect technology. They need the best available technology, deployed as rapidly as possible, with continuous improvement along the way.

7. The human element remains essential. Satellites provide data. Algorithms identify candidates. But expert human observers—the marine mammal biologists who have spent decades studying these animals—remain irreplaceable for validation, interpretation, and translation of detections into conservation action.

8. Infrastructure takes investment. GAIA’s achievements to date required sustained commitment from NOAA leadership, substantial philanthropic investment from Microsoft, interagency coordination with USGS and the Civil Applications Committee, and the dedicated effort of dozens of scientists and engineers. This level of investment is not sustainable for every endangered species or every conservation challenge. Scalable, transferable, democratized solutions remain the long-term goal.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

1. What is GAIA and who is building it?

GAIA (Geospatial Artificial Intelligence for Animals) is a NOAA-led initiative developing a cloud-based application for detecting whales in very high resolution satellite imagery. Partners include the U.S. Geological Survey, Microsoft AI for Good, the Naval Research Laboratory, and multiple NOAA Fisheries science centers. Version 0.1 was deployed in January 2026.

2. How does satellite whale detection actually work?

Very high resolution satellite imagery (0.31-meter panchromatic from WorldView-3) is preprocessed to correct geometric distortions, reduce noise, and enhance contrast. Microsoft AI for Good’s prototype algorithm identifies “interesting points”—pixel clusters with whale-like spectral signatures and spatial dimensions. Three independent expert annotators review these candidates in GAIA’s cloud application, drawing bounding boxes around confirmed whales. Validation reconciles discrepancies and ensures consensus. All annotation data is stored for subsequent machine learning model training.

3. Can satellites detect whales through clouds?

No. Optical satellite sensors (WorldView-3, WorldView-2, GeoEye) cannot see through clouds. Cloud cover is a major operational constraint. Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites can image through clouds, but GAIA does not currently support SAR imagery. This is a potential future expansion path.

4. How accurate is satellite whale detection?

The Cape Cod Bay case study is currently validating accuracy against independent aerial survey data. Preliminary results have not yet been published. GAIA’s rigorous validation protocol—three independent expert annotators per image, consensus reconciliation, comparison with established survey methods—will provide the conservation community’s first credible accuracy assessment.

5. Can satellites identify individual whale species?

Currently, GAIA focuses on detection (is there a whale?) rather than species identification. However, very high resolution imagery (0.31-meter) is sufficient to resolve morphological features like dorsal fin presence/absence and body shape. Species identification is a solvable computer vision problem contingent on sufficient training data. GAIA’s expansion to multiple species is actively building this capability.

6. How much does satellite imagery cost?

Tasking very high-resolution imagery is expensive—thousands of dollars per scene. Archival imagery is less expensive. GAIA’s access to U.S. government contracts through USGS and the Civil Applications Committee enables tasking that would be unaffordable for most academic or non-governmental researchers. Cost trajectories are downward as more commercial providers enter the market.

7. Why Cape Cod Bay for the first case study?

Cape Cod Bay offers three advantages: (1) predictable seasonal aggregation of North Atlantic right whales, ensuring target availability; (2) extensive validation data from the Center for Coastal Studies’ long-term aerial survey program; (3) manageable logistics and well-characterized oceanographic conditions. It is the ideal proving ground.

8. How does GAIA compare to passive acoustic monitoring?

Passive acoustics provide continuous presence data regardless of weather or daylight, but detect only vocalizing whales and provide imprecise localization. Satellite detection provides synoptic distribution data with precise geolocation, but requires favorable viewing conditions and cannot detect submerged whales. The methods are complementary, not competitive.

9. Will satellites replace aerial surveys?

No. Aerial surveys provide species identification, group size estimation, behavioral observation, photo-identification, and biopsy sampling—capabilities satellites cannot match. Satellite detection provides broad-scale distribution data that aerial surveys cannot economically achieve. The future is integrated, multi-platform monitoring.

10. What other species can GAIA detect?

GAIA is actively expanding to support Cook Inlet beluga whales (Alaska), Rice’s whales (Gulf of America), Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles (French Frigate Shoals), humpback, blue, and gray whales (Gulf of the Farallones), and Southern Resident killer whales (San Juan Islands and Juan de Fuca Strait) .

11. How many right whales remain?

The North Atlantic right whale population is estimated at 340–350 individuals. It remains one of the most endangered whale populations in the world.

12. What is “tasked” versus “archival” imagery?

Tasked imagery is collected upon request, over specific locations and time periods specified by the GAIA team. Archival imagery was collected in the past for other purposes and stored in commercial or government archives. Tasking enables coordination with validation surveys and optimal viewing conditions but is more expensive.

13. How do you know a satellite detection is really a whale?

GAIA’s validation protocol requires three independent expert annotators to confirm each detection. For the Cape Cod Bay case study, satellite detections are also compared against independent aerial survey data. Consensus-based expert validation is the current gold standard.

14. Can GAIA detect whales at night?

No. Optical satellite sensors rely on reflected sunlight. Night detection would require thermal infrared or synthetic aperture radar capabilities, which GAIA does not currently support.

15. What is the Strategic Initiative on Remote Sensing?

A NOAA-wide initiative to expand satellite-based monitoring capabilities across all Fisheries science centers. Under this initiative, GAIA is supporting image collection for priority species identified by each center.

16. How can I access GAIA data?

GAIA version 0.2 will add CSV export functionality for validated detections. Currently, access is limited to NOAA scientists and collaborators. The long-term vision includes broader data sharing with the conservation community.

17. What are “interesting points”?

Algorithm-identified candidate locations where a small area of pixels has a different spectral signature than surrounding water and is consistent in size with a possible whale. Interesting points are not confirmed detections; they are candidates for human expert review.

18. How long does it take from image acquisition to detection?

Current timelines are not publicly documented. Preprocessing, candidate generation, expert annotation, and validation require time. GAIA’s aspiration includes reducing latency to enable near-real-time dynamic management applications.

19. What is the difference between GAIA version 0.1 and 0.2?

Version 0.1 (January 2026) supports single-project annotation for Cape Cod Bay right whales. Version 0.2 (targeting 2026) will add multi-project support, streamlined API image loading, expanded sensor compatibility (WorldView-2, GeoEye), and CSV export.

20. How is GAIA funded?

GAIA is supported by NOAA Fisheries, with satellite tasking access facilitated by USGS and the Civil Applications Committee. Microsoft AI for Good provides pro bono technical development. Partner institutions contribute in-kind personnel and resources.

21. Can GAIA detect whales in the Southern Hemisphere?

GAIA’s current focus is U.S. waters and priority species under NOAA jurisdiction. However, the underlying technology is geographically transferable. Expansion to Southern Hemisphere species and habitats would require appropriate partnerships and funding.

22. What is the biggest technical challenge GAIA faces?

Building robust, generalizable machine learning models requires diverse training data covering the full range of real-world conditions (sea states, lighting, water clarity, surface behaviors). Acquiring this diversity through tasked imagery is expensive and time-consuming.

23. Where can I learn more about GAIA?

NOAA Fisheries maintains public web pages for Satellite Monitoring of North Atlantic Right Whales and the Geospatial Artificial Intelligence for Animals initiative. These pages are updated with current information.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Sana Ullah Kakar is a marine conservation technologist and former NOAA Fisheries Knauss Marine Policy Fellow. He holds a Ph.D. in oceanography from the University of Washington, where his dissertation research applied machine learning methods to passive acoustic monitoring of North Pacific right whales. Dr. Chen has served as a technical consultant to the UNESCO Ocean Biodiversity Information System and currently advises several non-governmental organizations on the integration of remote sensing technologies into marine protected area management. His 2025 field season included participation in the Center for Coastal Studies aerial survey program in Cape Cod Bay, providing direct experience with the validation data that underpins GAIA’s Cape Cod Bay case study. He writes regularly for https://thedailyexplainer.com/blog/ on emerging technologies in ocean conservation.

Connect: For inquiries regarding satellite monitoring partnerships, technology transfer, or speaking engagements, please use the contact form at https://thedailyexplainer.com/contact-us/.

FREE RESOURCES

1. NOAA Fisheries Satellite Monitoring Web Portal

Comprehensive public information on GAIA, the Cape Cod Bay case study, and North Atlantic right whale conservation applications. Includes technical documentation, partnership overviews, and links to published research. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england-mid-atlantic/science-data/satellite-monitoring-north-atlantic-right-whales

2. GAIA Cloud Application Technical Summary

Detailed documentation of GAIA version 0.1 architecture, preprocessing workflows, annotation protocols, and development roadmap. Essential reading for technologists considering similar applications. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england-mid-atlantic/science-data/geospatial-artificial-intelligence-animals

3. A Biologist’s Guide to the Galaxy (2020)

The foundational paper that articulated the vision and challenges of satellite marine mammal detection. Available through NOAA Institutional Repository.

4. UNESCO eDNA Expeditions Learning Portal

While focused on molecular monitoring rather than satellite remote sensing, this portal offers excellent training in biodiversity data collection, validation, and open-data principles transferable to satellite conservation applications. https://ednaexpeditions.org/training

5. USGS Earth Explorer

Public access portal for satellite imagery, including archival very high resolution data from commercial sensors. Essential resource for researchers beginning satellite detection work without tasked collection budgets. https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov

6. OBIS Ocean Biodiversity Information System

Global open-access database of marine species occurrences. Future integration with GAIA detections will create powerful synergies between satellite and in-situ monitoring. https://obis.org

7. For additional explanatory articles on emerging conservation technologies, visit https://thedailyexplainer.com/explained/

8. For curated resources on technology for social and environmental benefit, explore https://sherakatnetwork.com/category/resources/ and https://worldclassblogs.com/category/our-focus/

**9. For nonprofit leaders seeking guidance on scaling conservation technology initiatives, https://worldclassblogs.com/category/nonprofit-hub/ offers sector-specific case studies and https://sherakatnetwork.com/start-online-business-2026-complete-guide/ provides relevant organizational development frameworks.

10. For global policy updates on marine mammal conservation and the Endangered Species Act, follow https://thedailyexplainer.com/news-category/breaking-news/

DISCUSSION

The emergence of satellite AI as a viable tool for endangered whale detection raises profound questions that extend far beyond technical performance metrics.

What is the appropriate balance between automation and human expertise? GAIA’s current workflow relies on human expert review of algorithm-generated candidates. This is prudent; marine mammal biologists possess decades of accumulated observational expertise that cannot be reduced to training data. Yet the platform’s long-term scalability depends on increasing automation. Where should we draw the line? Which decisions must remain under human control, and which can we responsibly delegate to algorithms?

Who should have access to satellite detection capabilities? Very high resolution satellite imagery remains expensive. GAIA’s access is enabled by unique interagency partnerships and national security space contracts. This is not replicable for most conservation organizations, developing country marine protected areas, or indigenous communities managing ancestral waters. Is satellite monitoring destined to remain a capability of wealthy nations and large institutions? Or can we develop lower-cost, democratized alternatives?

How do we prevent misuse? Satellite surveillance capabilities developed for whale conservation could, in principle, be applied to vessel detection, fishing activity monitoring, or even human surveillance at sea. GAIA’s current mission is explicitly conservation-focused. But technologies do not respect organizational boundaries. What safeguards should be built into satellite AI platforms to prevent mission creep toward applications that infringe on privacy, livelihoods, or sovereignty?

What does “presence” mean in satellite imagery? A satellite detects a whale-shaped object at the surface. The whale is visible, breathing, available to be counted. But what about the whale submerged five minutes earlier, or five minutes later? What about the whale traveling through the area but not surfacing during the satellite’s 0.1-second imaging window? Satellite detection provides presence data with unknown detection probability. How should conservation managers incorporate this uncertainty into regulatory decisions that affect shipping, fishing, and offshore development?

I believe these questions are not peripheral to GAIA’s mission; they are central. Technology development and ethical reflection must proceed in parallel. The GAIA team’s commitment to transparency—public documentation, open validation protocols, multi-stakeholder collaboration—is an encouraging foundation. But the conversation must expand beyond NOAA and its immediate partners to include the broader conservation community, affected industries, and the public whose waters and wildlife are at stake.

What do you believe? If you are a marine protected area manager considering how satellite monitoring might support your conservation objectives, what are your highest-priority questions? If you are a technologist working on similar computer vision applications, what lessons have you learned about building trust in algorithmic decision-making? If you are a mariner navigating waters where satellite-detected whales may trigger speed reduction requirements, how can detection systems earn your confidence?

Share your perspectives. The future of satellite AI in marine conservation will be shaped not only by scientists and engineers but by the managers, mariners, and citizens who decide whether to trust and act upon its outputs.

For continued discussion of ocean conservation policy and emerging monitoring technologies, visit https://thedailyexplainer.com/category/global-affairs-politics/. To submit a story about your community’s experience with satellite-based monitoring, contact our editorial team at https://thedailyexplainer.com/contact-us/. For terms governing reproduction of this content, please review https://thedailyexplainer.com/terms-of-service/. For additional perspectives on technology for conservation and social benefit, explore https://worldclassblogs.com/category/blogs/ and https://sherakatnetwork.com/category/blog/