obots in space operate at different levels of independence depending on the task complexity, communication delay, and required safety.

Introduction – Why This Matters

I was watching a video feed from inside the International Space Station (ISS). An astronaut, her hands occupied with a delicate biological experiment, was floating in place. “CIMON,” she said calmly, “please pull up the procedure for step 7, and magnify the diagram of the centrifuge.” From a nearby panel, a floating, softball-sized sphere with a friendly screen face chirped an acknowledgement. It navigated smoothly to her, displaying the requested information. In that moment, CIMON wasn’t just a tool; it was a crewmate, extending the astronaut’s cognitive and physical reach. It was a glimpse into a fundamental shift: the future of space exploration isn’t just humans or robots—it’s humans with robots.

For curious beginners, space robots might conjure images of clunky Mars rovers. For professionals, they represent the frontier of human-robot interaction (HRI) in the most demanding environment imaginable. What I’ve learned from engineers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center and robotics startups is this: The goal isn’t to replace astronauts, but to create a symbiotic partnership where each does what they do best. Humans provide creativity, intuition, and high-level problem-solving. Robots provide superhuman endurance, precision, and the ability to work in environments lethal to humans. In 2025, with Artemis targeting a sustained lunar presence and Mars on the horizon, developing capable robotic partners has moved from R&D to a critical path item. This article will explore how humanoid robots, dexterous manipulators, and intelligent virtual assistants are being engineered to become the indispensable crew of tomorrow.

Background / Context: From Tools to Teammates

The history of robotics in space is one of increasing capability and autonomy.

- The Mechanical Arm Era (1980s-2000s): The Canadarm series on the Space Shuttle and ISS were revolutionary—powerful, precise tools operated via direct telepresence by astronauts. They were extensions of human will, but required constant control.

- The Autonomous Rover Era (1990s-Present): Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance on Mars represented a leap in autonomy. They could navigate terrain, select science targets, and perform limited self-care, but their interactions were with rocks and soil, not people, and over vast time delays.

- The Intra-Vehicular Assistant Era (2010s-Present): Robots moved inside the habitat. Robonaut 2 (R2) tested humanoid form and dexterity on the ISS. CIMON (Crew Interactive MObile companioN) and its successor CIMON-2 pioneered the free-flying, voice-activated assistant.

- The Teammate Era (2020s and Beyond): We are now entering an era where robots are designed from the ground up as collaborative agents. They share space with humans, understand natural language, anticipate needs, and perform complex physical tasks either autonomously or through intuitive guidance. This shift is driven by the harsh economics of deep-space missions: every hour of astronaut time is astronomically expensive, and every extra kilogram of life support is a burden. Robots that can take over routine, dangerous, or tedious work multiply the effectiveness and safety of the human crew.

Key Concepts Defined

- Humanoid Robot: A robot with a body shape built to resemble the human body, typically with a torso, head, two arms, and two legs. The design is not for aesthetics but for functionality—to operate in environments built for humans, using human tools.

- Dexterous Manipulation: The ability of a robot hand or gripper to perform fine, coordinated movements for tasks like turning a valve, handling a fragile sample, or assembling a component.

- Human-Robot Teaming (HRT): A collaborative partnership where humans and robots share tasks, with the robot capable of some autonomy and able to understand the human’s intent and state.

- Virtual Assistant (in space): An AI-powered software agent, often with a visual interface (avatar) and voice interaction, designed to help astronauts with procedures, information retrieval, scheduling, and system monitoring. It can be embedded in a free-flying robot (like CIMON) or in a fixed station panel.

- Supervised Autonomy: A mode where a robot performs a complex task on its own, but a human provides high-level oversight, approval for key steps, or can interrupt and redirect if needed.

- Telepresence with Haptic Feedback: Remote operation of a robot where the human operator receives not just visual and auditory feedback, but also force feedback through a specialized controller, allowing them to “feel” what the robot is touching.

- Embodied AI: Artificial intelligence that is situated in a physical body (a robot), allowing it to learn from and interact with the real world through sensors and actuators, as opposed to purely software-based AI.

How It Works: The Three Classes of Robotic Companions

Class 1: The Humanoid Co-Worker (e.g., NASA’s Valkyrie, Tesla’s Optimus)

These robots are designed to go “where the astronaut goes” and do “what the astronaut does,” especially for tasks too dangerous or tedious for humans.

- Physical Design:

- Torso & Limbs: Built with a combination of rigid structures and compliant elements to absorb impacts and interact safely with humans and delicate equipment.

- End Effectors (Hands): The most critical component. Valkyrie’s hands have three fingers and a thumb, each with multiple joints, fingertip sensors, and a degree of compliance to grip a wide range of tools—from a wrench to a scientific instrument.

- Perception Suite: Multiple cameras (stereo, depth-sensing), LiDAR, and torque sensors in every joint create a rich 3D model of the environment and the robot’s own body position.

- How It Operates:

- Task Loading: An astronaut or ground controller gives a high-level command: “Inspect the external panel on Airlock Module 2.”

- Autonomous Planning: The robot’s AI breaks this down: navigate from current location to airlock (using SLAM—Simultaneous Localization and Mapping), identify the correct panel, scan it with its cameras, and perhaps use a tool to check bolt torque.

- Execution with Oversight: The robot performs the task, streaming video and sensor data. The human monitors. If the robot encounters an unexpected problem (a blocked path), it pauses and asks for guidance.

- Key Technology: Whole-Body Control. This software allows the robot to use its entire body to maintain balance, apply force, or manipulate objects. If it needs to push a heavy cart, it won’t just use its arms; it will brace its legs and lean its torso, just like a human.

Class 2: The Specialized System Assistant (e.g., GITAI’s Robotic Arm, Astrobee)

These are robots designed for specific, repetitive tasks or to provide mobile sensing within a habitat.

- GITAI’s S1 Robotic Arm: This arm is being tested for external satellite servicing and lunar base construction.

- How it works: It can be mounted on a rover or habitat. An operator on Earth (or in a nearby habitat) uses a virtual reality interface to control it. They see through the robot’s cameras and use VR controllers to “reach out and grab” a bolt. The system translates their hand movements into precise robot arm motions in near real-time. This is telepresence, not full autonomy, but it allows a human’s expertise to be applied from a safe location.

- NASA’s Astrobee: A trio of free-flying, cube-shaped robots on the ISS.

- How they work: They use electric fans for propulsion in microgravity. Their primary role is automated monitoring. They can be scheduled to fly pre-planned routes, using cameras and sensors to take inventory, measure air quality, or record acoustic levels, freeing crew time. They can also be used as a mobile camera for ground controllers to “visit” the station.

Class 3: The Cognitive & Social Companion (e.g., CIMON, AI Health Coaches)

These systems focus on supporting the astronaut’s cognitive load and psychological well-being.

- CIMON-2’s Architecture:

- Voice Interface: Powered by IBM’s Watson, it understands natural language, context, and specific crew member voices.

- Face Recognition: Its screen can display an empathetic avatar and recognize which astronaut it’s speaking to.

- Task Integration: It’s connected to station databases, procedures, and manuals. An astronaut can ask: “CIMON, what were the results of yesterday’s plant growth experiment?” or “Show me an animation of the next repair step.”

- Social Cues: It’s programmed to be helpful, polite, and even exhibit mild humor to reduce the stress of complex procedures.

- Future AI Health Assistants: These are in development. Using wearable biometric sensors (heart rate, sleep quality, voice stress analysis), an AI could privately note signs of elevated stress or fatigue in a crew member. It might then suggest: “I notice your sleep was restless. Would you like to schedule an extra 30 minutes for the mindfulness VR module today?” This proactive care is crucial for long-duration missions.

Comparison of Robotic Companion Types

| Type | Example | Primary Role | Key Technology | Autonomy Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanoid Co-Worker | NASA Valkyrie, Apptronik Apollo | Dangerous EVA, routine maintenance, setup | Dexterous manipulation, whole-body control, supervised autonomy | High (Task-Level) |

| Specialized Assistant | GITAI S1 Arm, Astrobee | Precise assembly, inventory, mobile sensing | Telepresence VR, computer vision, automated navigation | Medium (Teleoperated/Scripted) |

| Cognitive Companion | CIMON-2, future AI Coach | Procedure guidance, information retrieval, psychological support | Natural Language Processing, affective computing, data integration | Variable (Conversational/Advisory) |

Why It’s Important: The Force Multiplier for Deep Space

Robotic companions are not a sci-fi luxury; they are a strategic necessity for three compelling reasons:

- Maximizing Precious Human Time: On a Mars mission, every minute of an astronaut’s time is the culmination of billions of dollars of investment. Having robots perform “housekeeping” tasks (filter cleaning, system checks, inventory) or setup tasks (preparing a worksite, deploying equipment) gives the human crew more time for the irreplaceable work: scientific discovery, exploration, and high-level decision-making.

- Enabling Crew Safety and Mission Resilience: Robots are ideal for “first in, last out” operations.

- Before Crew Arrival: Robotic precursors could land on Mars, activate a habitat, verify life support systems, and begin resource extraction (ISRU), ensuring the environment is safe and functional for humans.

- During Hazardous Operations: A humanoid robot could perform emergency external repairs during a solar storm, when it’s unsafe for astronauts to do EVAs.

- As a Supplemental Caregiver: In a medical emergency, a robot could fetch supplies, hold equipment, or provide step-by-step procedural guidance from Earth’s medical team, assisting the crew’s medical officer.

- Mitigating Psychological and Cognitive Load: The isolation and confinement of deep space are immense psychological challenges. An AI companion like CIMON provides a form of social interaction and reduces procedural stress. Furthermore, by acting as an always-available, omniscient “procedural memory,” it prevents cognitive errors during complex tasks. Supporting mental health is as critical as physical health, a point underscored in our partner resource on psychological wellbeing.

- Reducing Launch Mass and Mission Cost: While the robot itself has mass, it can offset far more mass over time. A dexterous robot that can repair components eliminates the need to launch thousands of spare parts. A construction robot that can build radiation shields from local regolith means you don’t have to launch the shields from Earth.

Sustainability in the Future: The Integrated, Learning Crew

The future of human-robot teaming in space is one of deep integration and continuous learning.

- The “Hive Mind” Crew: Individual robots (humanoid workers, flying sensors, stationary arms) will be networked, sharing perception data and task status. A humanoid might call on a free-flyer to “bring me a 10mm socket from locker B,” creating a fluid, multi-agent team.

- Robots that Learn from Demonstration: Instead of complex programming, an astronaut will simply show the robot a task. Using imitation learning and reinforcement learning, the robot will generalize from a few demonstrations to perform the task autonomously, even adapting to slight variations. “Do it like this” becomes the primary programming language.

- Proactive Support AI: The cognitive assistant will evolve from reactive (answering questions) to proactive. By analyzing crew schedules, biometrics, and system data, it might say: “You have a 4-hour EVA after lunch. Your hydration levels are sub-optimal. I’ve moved your water break up by 30 minutes,” or “The spectral analysis from the rover matches a rare mineral. I’ve highlighted it on your geology map for tomorrow’s traverse.”

- Long-Term Autonomy and Self-Maintenance: For truly distant missions, robots must be able to maintain themselves—replacing worn gears, recalibrating sensors. Research into self-reconfigurable modular robotics imagines robots that can change their own shape and function, a cornerstone of sustainable, long-duration exploration.

Common Misconceptions

- Misconception: “They’re trying to replace astronauts with robots.” Reality: The official stance of NASA and other agencies is clear: Robots enable human exploration. They handle the dull, dirty, and dangerous work so humans can focus on the tasks requiring human intelligence, creativity, and adaptability. The goal is augmentation, not replacement.

- Misconception: “Humanoid robots are just for show; wheels or tracks are always better.” Reality: The humanoid form is an engineering solution to a specific problem: legacy infrastructure. Spacecraft, airlocks, ladders, and tools were designed for the human form. A robot that can climb a ladder, squeeze through a hatch, and use the same socket wrench as an astronaut is infinitely more versatile in a human-built environment than a wheeled robot.

- Misconception: “AI in space is too risky; it could malfunction or become hostile.” Reality: Space-grade AI is built with functional safety as the top priority. These are not general, unbounded AIs. They are narrowly focused expert systems with strict operational boundaries and multiple, independent fail-safes. The “rogue AI” trope is a distraction from the real, manageable engineering challenges of reliability and verification.

- Misconception: “Astronauts will find robots annoying or won’t trust them.” Reality: This is a key area of study—human factors engineering. The design of robot behavior (how it moves, communicates, requests attention) is carefully crafted to build appropriate trust. Early tests on the ISS have shown that when robots are useful and predictable, crews quickly integrate them as valuable tools and even appreciate their presence.

Recent Developments (2024-2025)

- Valkyrie’s Earthly Trials: NASA’s humanoid robot Valkyrie (R5) has been leased to companies like Apptronik for terrestrial development. It’s currently being tested in a simulated Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) lab, practicing tasks like connecting electrical plugs and inspecting damaged equipment—skills directly transferable to a lunar base.

- The Artemis “CLPS” Robotic Payloads: NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) missions are booking spots for robotic demonstrators. A mission slated for 2027 will test a small robotic arm for regolith handling and a rover with a simple manipulator, proving technologies for future construction.

- SpaceX’s “Optimus” and Lunar Ambitions: While focused on Earth, Tesla’s Optimus humanoid robot program is being closely watched by the space community. The underlying technologies—low-cost actuators, efficient battery-powered mobility, and AI learning—are precisely what future space robots need. SpaceX has hinted at adapting such platforms for its Starship lunar and Mars plans.

- AI “Crewmate” Software Upgrades: On the ISS, the software for systems like Astrobee and the upcoming SOLAR (a more advanced free-flyer) is being upgraded with better natural language understanding and the ability to accept complex, multi-step commands.

- Haptic Telepresence Breakthrough: In 2024, researchers at ESA and the University of Colorado demonstrated a time-delay-compensated haptic system that allows an operator to feel realistic force feedback when controlling a robot on a simulated Mars mission, despite the signal delay. This is a game-changer for precise remote surgery or repair.

Success Story: The Robonaut 2 (R2) Legacy

While its time on the ISS had hardware challenges, Robonaut 2 was a monumental success in proving concepts. Developed jointly by NASA and General Motors, R2 was the first humanoid robot in space.

- What it proved:

- Dexterity in Microgravity: Its hands, with 12 degrees of freedom each, could operate tools, flip switches, and handle flexible materials like cloth.

- Safe Proximity Operation: It worked alongside astronauts without incident, demonstrating that humanoid robots could be trusted in close quarters.

- Telepresence Value: Ground controllers could don a VR headset and control R2’s arms and hands to perform tasks, showing the potential for ground-based experts to “visit” the station.

- The Legacy: R2’s “family” continues. Its core technologies directly informed the design of Valkyrie. The lessons learned about joint design for the space environment, thermal management, and software architecture are foundational to all current humanoid space robot programs. R2 wasn’t the finished product; it was the essential prototype that de-risked the entire endeavor.

Real-Life Examples

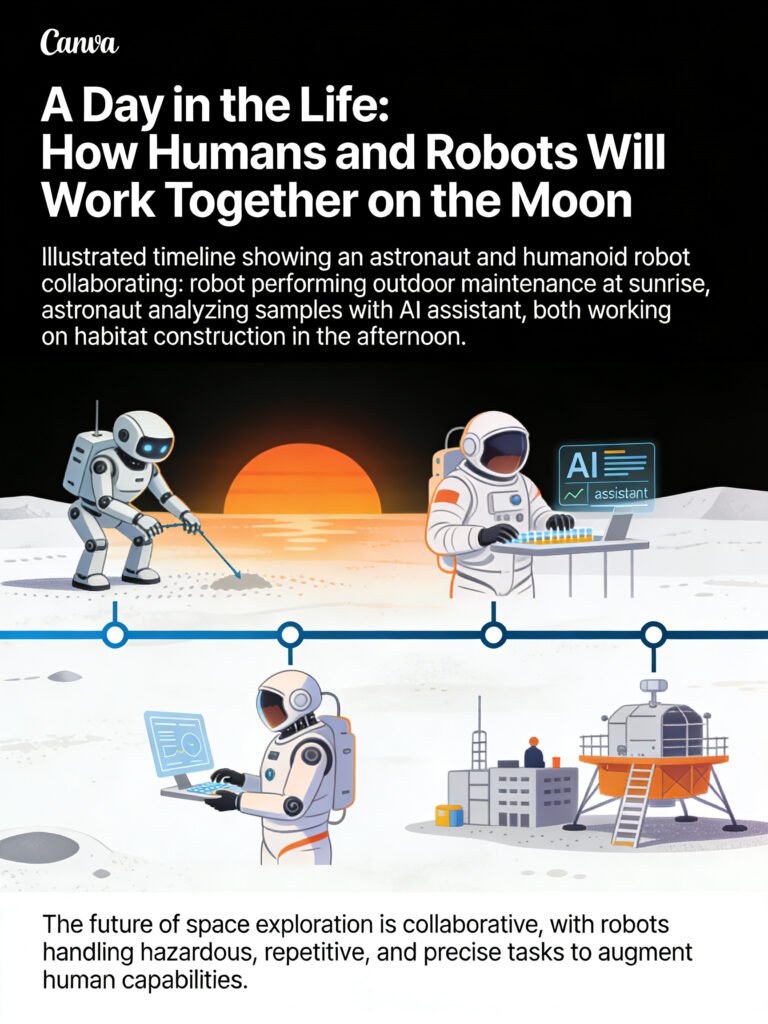

- For a Lunar Base (2030s Scenario):

- Before Sunrise: A team of humanoid robots exits the habitat. One begins inspecting and cleaning solar panels. Another uses a regolith-moving attachment to cover habitat modules with a radiation-shielding layer of dirt.

- During the Day: An astronaut prepares for a geology traverse. They tell the AI assistant: “Prepare EVA suit 3 and load the geology tools from locker Alpha.” The AI coordinates with a stationary robotic arm in the suit-up area to have everything ready.

- At the Worksite: The astronaut discovers a complex rock formation. They deploy a small, flying scout drone from their backpack. “Map this outcrop and highlight veins with different spectral signatures.” The drone autonomously flies a pattern, building a 3D model.

- For a Mars Transit Vehicle (Deep Space Habitat):

- An astronaut is feeling isolated. They have a conversation with the AI companion, which has been programmed with therapeutic dialogue techniques. It suggests a collaborative VR game or a call with family using the delayed-communication buffer.

- A critical carbon dioxide scrubber shows a pressure anomaly. A snake-like inspection robot is sent into the tight ductwork to locate and diagnose the leak, sending back video for the crew to assess.

- For In-Space Manufacturing/Assembly:

- In Earth orbit, a large, industrially focused robotic arm (like the one being developed by Vast Space or Sierra Space) autonomously assembles trusses and connects prefab modules for a new commercial space station, guided by high-level instructions from engineers on Earth.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The image of the lone astronaut, heroically facing the void, is being replaced by a more powerful, more realistic vision: the integrated crew. In this vision, humans and robots form a cohesive unit, each member playing to their innate strengths. The human provides the spark of curiosity, the wisdom of experience, and the resilience of the spirit. The robot provides the tireless labor, the unerring precision, and the presence in places where flesh cannot go.

Developing these robotic companions is one of the most complex interdisciplinary challenges we face—melding mechanical engineering, computer science, cognitive psychology, and systems design. But the payoff is a future where human exploration is safer, more sustainable, and far more productive. The robots aren’t coming for the astronauts’ jobs; they’re coming to be their partners, their tools, and in a very real sense, their guardians.

Key Takeaways Box:

- Symbiosis, Not Substitution: Robots are designed to augment human capabilities, not replace them, handling tedious, dangerous, or precise tasks.

- Form Follows Function: The humanoid shape is a practical choice for operating in human-designed environments with human tools.

- Autonomy is a Spectrum: From teleoperation to supervised autonomy to full independence, different tasks require different levels of robot self-sufficiency.

- The Cognitive Load is a Mission Risk: AI assistants that manage procedures, information, and even psychological well-being are critical for crew performance on long missions.

- We Are in the Prototype Phase: Systems like Valkyrie, CIMON, and Astrobee are advanced testbeds. The next decade will see them evolve into operational systems for the Moon and beyond.

For more detailed analysis on the technologies shaping our future, explore the latest in our blog at The Daily Explainer.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What’s the difference between Robonaut, Valkyrie, and Boston Dynamics’ Atlas?

- Robonaut 2 (R2): A technology demonstrator focused on dexterous manipulation and telepresence in the microgravity interior of the ISS.

- Valkyrie (R5): The next generation, built for planetary surfaces. It’s more robust, has legs for walking on terrain, and is designed for higher levels of autonomy in dirty, outdoor environments.

- Boston Dynamics Atlas: A terrestrial research platform focused on dynamic mobility (running, parkour) and balance. Its control algorithms are influential, but it’s not hardened for space environments (radiation, vacuum, dust).

2. Can these robots perform spacewalks (EVAs)?

That is a primary goal for humanoid robots like Valkyrie. They would need to be equipped with an EVA suit of their own—a protective shell with life support for its electronics. They could perform pre-programmed external inspections, repairs, or setups before or after human EVAs, reducing crew risk.

3. How do you communicate with a robot on Mars with a 20-minute delay?

You don’t, for direct control. This is why supervised autonomy is key. You give it a task: “Deploy the seismic sensor array at these coordinates.” The robot plans and executes the multi-hour task on its own, sending back periodic status reports. You only intervene if it reports a problem it can’t solve.

4. What happens if a robot breaks down on Mars?

Redundancy and repairability are designed in. A mission might send two identical humanoids so one can repair the other. They will be designed with modular components that can be replaced using tools they themselves can wield. The human crew, when they arrive, would also be trained in robot maintenance.

5. Isn’t it creepy to have a robot with a face watching you all the time?

This is a serious human factors concern. Designers are careful. CIMON has a simple, friendly face on a screen to aid social interaction. Valkyrie has a more utilitarian “head” that houses sensors; it’s not designed to be overly anthropomorphic. The key is to make the robot’s behavior predictable and useful, which builds comfort, not creepiness.

6. Could a robot provide emergency medical care?

Not as a doctor, but as a surgical assistant or telemedicine terminal. A robot with steady hands could hold instruments, apply clamps, or even perform sutures under the real-time guidance of a remote surgeon on Earth (via telepresence with haptic feedback). It could also fetch supplies and monitor patient vitals.

7. How are robots powered on the Moon or Mars?

Primarily by rechargeable batteries, topped up by solar panels during the day. For long-duration missions in shadowed regions (lunar poles), small radioisotope power sources (like the ones used on Mars rovers) might be necessary to provide continuous heat and trickle charge.

8. What about space radiation damaging robot electronics?

Robots use radiation-hardened (rad-hard) or radiation-tolerant electronic components, just like spacecraft. Critical systems may have triple modular redundancy (three identical processors that vote on every decision). Their software is also designed to recover from memory errors caused by radiation strikes.

9. Will astronauts need special training to work with robots?

Yes, but the goal is to make the interaction as intuitive as possible. Training will focus on task delegation (what to let the robot do autonomously), monitoring techniques, and troubleshooting procedures. The interface will likely be voice and tablet-based, not complex programming.

10. Could robots have “rights” or be considered crew members?

This is a futuristic ethical and legal question. Currently, they are considered equipment. However, as they become more autonomous and make more consequential decisions, debates about machine agency and responsibility may emerge, a topic that intersects with broader global affairs and policy discussions on AI ethics.

11. How small can space robots be?

Very. Cubesats are robots the size of a loaf of bread. “Swarm” concepts imagine thousands of smartphone-sized robots released to explore the caverns of an asteroid, communicating and mapping collectively. Size is dictated by the task.

12. Can robots be used to grow food in space?

Yes, as agricultural tenders. They could be programmed to monitor plant health in hydroponic bays, adjust lights and nutrients, and even perform harvesting, pruning, and pollination tasks with delicate grippers.

13. What’s the biggest unsolved technical challenge for space humanoids?

Autonomous dexterous manipulation in unstructured environments. Picking up a known tool in a lab is one thing. Navigating a chaotic, dusty planetary garage, finding a specific wrench in a pile, and using it to tighten a bolt that has corroded—that requires a level of perception, reasoning, and adaptive force control we are still perfecting.

14. How do you simulate space conditions for testing these robots?

- Neutral Buoyancy Labs: Underwater pools simulate microgravity for testing movement and manipulation.

- Vacuum Chambers: Test operation in space-like vacuum and thermal conditions.

- Analog Sites: Places like the NASA’s “Rockyard” or volcanic terrain in Hawaii simulate Martian or lunar geology for mobility testing.

- “Mars Yards”: Indoor sandboxes with red dirt and rocks for rover testing.

15. Are there any artistic or creative roles for robots in space?

Potentially. A robot could be used to document missions from unique angles (a free-flyer filming a spacewalk). More speculatively, a robot with dexterous hands could assist in space-based manufacturing of art or create structures that are both functional and beautiful.

16. How does the development of space robotics benefit Earth?

The technologies spin off dramatically: Robotic surgery was advanced by NASA telepresence research. Better prosthetics come from dexterous robot hand design. Autonomous navigation software finds its way into self-driving cars and drones. The extreme requirements of space drive innovation that diffuses into the economy, much like the entrepreneurial drive seen in resources from Sherakat Network.

17. Could a robot be programmed with a “personality”?

To a limited, functional extent. An AI assistant’s voice and interaction style could be calibrated—more formal for procedure guidance, more conversational for general interaction. However, the primary goal is utility and trust, not entertainment. A fake or distracting personality would be counterproductive.

18. What’s the power consumption of a humanoid robot like Valkyrie?

It varies, but during high-torque activities, it could consume several kilowatts—similar to a large household appliance. This is why activity is carefully scheduled around power availability, and low-power “idle” or “sleep” modes are crucial.

19. How do you prevent a floating robot like CIMON from bumping into things?

It uses a combination of ultrasonic sensors, cameras, and infrared sensors to create a 3D map of its immediate surroundings (obstacle avoidance). Its propulsion fans are precisely controlled to make small, gentle movements. It’s programmed to give astronauts a wide berth.

20. Will robots eventually build other robots in space?

This is the long-term vision for self-replicating systems, a concept for exponential infrastructure growth. We are far from that, but intermediate steps include robots using 3D printers to fabricate simple parts or tools from raw materials, a step towards self-sufficiency.

21. How does the partnership between government (NASA) and private companies (SpaceX, Apptronik) work in this field?

NASA often funds early-stage R&D and sets requirements. It then partners with or purchases services from commercial companies to develop and operate systems. For example, NASA’s “Tipping Point” grants fund companies like Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines to develop lunar robotics. This public-private model accelerates innovation, a dynamic also seen in other sectors covered in breaking news on technology.

22. Could robots be used for dangerous science, like sampling a geyser on Enceladus?

Absolutely. This is a perfect example of a “dirty and dangerous” job. A ruggedized, sterilized robot could be sent to collect samples from these dynamic features, where the environment is hazardous and potentially contaminating, while humans observe from a safe distance in orbit.

23. Where can I see videos of these robots in action?

The best sources are the NASA JPL Robotics YouTube channel, NASA’s Technology Transfer website, and the channels of companies like Boston Dynamics, Apptronik, and GITAI.

About the Author

Sana Ullah Kakar is a human factors engineer and technology journalist specializing in the intersection of humans and complex systems. They have a background in cognitive science and have worked on usability testing for both consumer robotics and aerospace interfaces. This unique perspective allows them to focus not just on what space robots can do, but on how astronauts will actually live and work with them. They are fascinated by the challenge of designing trust into machines and believe that the success of future missions hinges as much on smooth human-robot interaction as on rocket propulsion. At The Daily Explainer, they strive to make the human side of advanced technology relatable and clear. When not writing, they can be found tinkering with old robots or hiking—activities that, in their view, are both about exploring the boundaries of agency and environment. You can reach out via our contact page.

Free Resources

- NASA Robotics Alliance Project: Educational resources, competition information, and profiles of NASA’s robotic projects.

- IEEE Robotics and Automation Society, Space Robotics Technical Committee: Academic papers, webinars, and conference information on the cutting edge of space robotics research.

- The DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics (German Aerospace Center): World-leading research with excellent public documentation on projects like Rollin’ Justin and David.

- “Robots in Space” by NASA History Division: A detailed historical overview of the evolution of space robotics.

- Simulators: Open-source robot simulators like Gazebo are used by professionals and hobbyists to model robot behavior; NASA often releases models of its robots.

- Related Perspectives: For insights into how such advanced projects integrate into a broader societal and exploratory context, explore our partner site’s section on Our Focus.

Discussion

Would you feel comfortable sharing a small habitat on a two-year Mars mission with a humanoid robot as a crewmate? What task would you most want to delegate to a robotic assistant in space? Do you think the benefits of AI companions for mental health outweigh the potential privacy concerns? Share your thoughts on the future of human-robot relationships in the final frontier.