The Campaign Finance Ecosystem: Tracing money flows from donors to political outcomes and policy influence.

Introduction: The Currency of Political Power

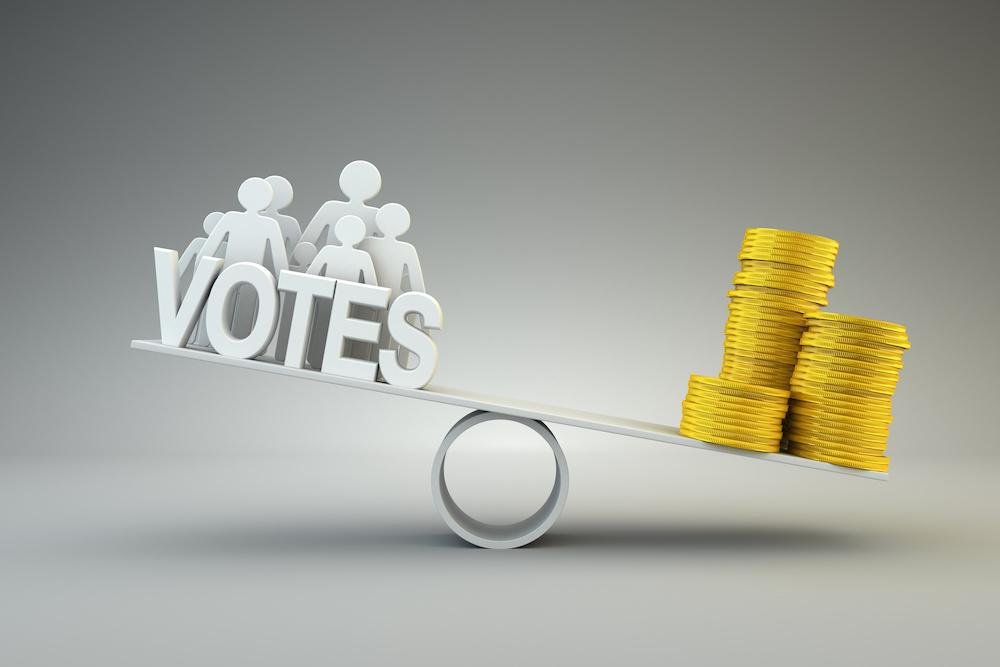

In democracies worldwide, the relationship between money and political power represents one of the most persistent and controversial challenges to representative government. Campaign finance—the funding of electoral campaigns and political operations—serves as the lifeblood of modern political competition, yet its influence on policy outcomes and democratic integrity remains intensely debated. From multi-billion dollar presidential campaigns in the United States to state-funded election systems in European democracies, how societies choose to finance political competition fundamentally shapes whose voices are heard and which interests prevail in the policymaking process.

The stakes extend far beyond electoral outcomes alone. Political influence purchased through campaign contributions, lobbying expenditures, and political advertising can determine which policies are prioritized, which regulations are implemented, and ultimately, how power is distributed within society. Understanding campaign finance systems is therefore essential not only for comprehending electoral politics but for grasping the fundamental mechanics of how democratic governance functions—and sometimes fails to function—in practice. This examination of money’s role in politics reveals much about the health of democracies and the ongoing struggle between equal citizenship and unequal economic power. For more analysis of how political systems operate, visit our Explained section.

Background/Context: The Historical Evolution of Money in Politics

Early Developments: From Patronage to Regulation

The relationship between wealth and political influence predates modern democracy itself. In ancient Rome, wealthy patrons financed political careers in expectation of future favors, while in pre-revolutionary France, the sale of offices created a direct market for political power. The emergence of representative democracy in the 18th and 19th centuries transformed but did not eliminate these dynamics, as the costs of political campaigning created new avenues for wealthy influence.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the first serious attempts to regulate money in politics. The United States passed the Tillman Act in 1907, banning corporate contributions to federal campaigns, while the United Kingdom’s Corrupt and Illegal Practices Prevention Act of 1883 established spending limits for parliamentary candidates. These early regulations reflected growing concern about the corrupting influence of money, though enforcement mechanisms often remained weak.

The Television Age: Rising Costs and New Challenges

The mid-20th century transformation of political campaigning, particularly the rise of television advertising, dramatically increased the cost of competitive elections. Between 1950 and 1970, average spending in US congressional races increased tenfold in real terms, creating unprecedented pressure on candidates to raise large sums. This period saw the emergence of political action committees (PACs) in the United States and similar organizations elsewhere, creating new channels for organized interests to influence elections.

The Watergate scandal in the United States prompted a new wave of campaign finance reforms in the 1970s, including the Federal Election Campaign Act amendments that established contribution limits and created the Federal Election Commission. Similar reforms occurred in other democracies, though approaches varied significantly based on political culture and constitutional frameworks.

The Modern Era: New Technologies and Evolving Systems

Recent decades have witnessed both continuity and change in campaign finance. The rise of digital campaigning has created new fundraising opportunities through small-donor online contributions, as demonstrated by Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign and Bernie Sanders’ subsequent operations. At the same time, court decisions like Citizens United in the United States have removed previous restrictions, enabling unprecedented spending by super PACs and other independent groups.

Globally, approaches to campaign finance continue to diverge, with some countries moving toward greater public funding and transparency while others struggle with enforcement of existing regulations. The ongoing digital transformation of campaigning, as explored in our analysis of Digital Democracy Technology, has added new complexity to these longstanding challenges.

Key Concepts Defined: The Lexicon of Political Finance

Funding Mechanisms and Structures

- Political Action Committees (PACs): Organizations that pool campaign contributions from members and donate those funds to campaigns for or against candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation.

- Super PACs: Independent expenditure-only political committees that may raise unlimited sums from corporations, unions, and individuals but are not permitted to contribute to or coordinate directly with parties or candidates.

- Dark Money: Political spending by organizations that are not required to disclose their donors, typically structured as social welfare organizations or trade associations under relevant tax laws.

- Public Financing Systems: Government funding of political campaigns or parties, often designed to reduce candidates’ dependence on large private donations and equalize electoral competition.

- Matching Funds Systems: Public financing approaches where government funds match small private donations at a specified ratio, amplifying the impact of small contributions.

Regulatory Frameworks

- Contribution Limits: Legal restrictions on the amount individuals, organizations, or parties can donate to candidates, parties, or other political entities.

- Expenditure Limits: Caps on total campaign spending by candidates, parties, or other political actors, used in some countries to control campaign costs and reduce financial advantages.

- Disclosure Requirements: Legal mandates that campaigns, parties, and other political actors publicly report information about their donors and expenditures.

- Foreign Interference Bans: Prohibitions on political donations from foreign nationals or entities, aimed at preventing external influence on domestic politics.

Influence Mechanisms

- Lobbying Expenditures: Money spent to influence legislation or government decisions through direct advocacy, distinct from but often related to campaign contributions.

- Independent Expenditures: Political spending by individuals or groups independently of candidates and parties, typically on advertising or other communications advocating for or against political candidates.

- Bundling: The practice of combining multiple individual campaign contributions from networks of donors, allowing individuals to effectively deliver larger total sums to candidates.

How It Works (Step-by-Step): The Campaign Finance Ecosystem

Phase 1: Fundraising and Resource Accumulation

Step 1: Donor Identification and Cultivation

Modern campaigns employ sophisticated methods to identify potential donors:

- Wealth screening using commercial databases and public records

- Political affinity modeling based on past donation patterns and political engagement

- Network mapping to identify socially or professionally connected potential donors

- Digital prospecting through online engagement and list building

Step 2: Contribution Solicitation

Multiple channels facilitate donation collection:

- High-dollar events with premium access to candidates

- Digital fundraising through email, social media, and dedicated platforms

- Direct mail programs targeting proven donors

- Bundler networks leveraging influential supporters’ personal networks

- Membership programs with recurring contribution options

Step 3: Compliance and Reporting

Legal frameworks require meticulous financial tracking:

- Donor information verification ensuring eligibility and identity

- Contribution tracking against legal limits by donor category

- Expenditure categorization according to regulatory requirements

- Regular reporting to oversight agencies and public disclosure

Phase 2: Expenditure and Strategic Deployment

Step 4: Budget Allocation Decisions

Campaigns face strategic choices in resource deployment:

- Media spending allocation across television, digital, radio, and print

- Geographic targeting based on electoral importance and competitiveness

- Demographic targeting focusing on persuadable voter segments

- Operational investment in staff, offices, and field operations

- Contingency reserves for unexpected opportunities or challenges

Step 5: Advertising and Voter Contact

Financial resources translate into voter influence through:

- Television and radio advertising purchases in relevant markets

- Digital advertising campaigns with sophisticated targeting

- Direct mail programs to specific voter households

- Field operations including door-to-door canvassing and phone banking

- Get-out-the-vote efforts in election’s final stages

Step 6: Independent Expenditure Coordination

Outside groups operate alongside formal campaigns:

- Issue advocacy that stops short of explicit electioneering

- Candidate-specific advertising without formal coordination

- Voter mobilization efforts targeting specific constituencies

- Opposition research and information dissemination

Phase 3: Post-Election Influence and Accountability

Step 7: Debt Retirement and Financial Reconciliation

After elections, campaigns address financial obligations:

- Outstanding vendor payment and operational debt settlement

- Surplus fund management according to legal requirements

- Legal compliance completion for final reporting cycles

- Donor relationship maintenance for future political activities

Step 8: Influence Capitalization

Successful candidates face expectations from supporters:

- Policy priority alignment with major donor interests

- Access provision to financial supporters

- Appointment considerations for key positions

- Legislative attention to donor-preferred issues

Step 9: Ongoing Political Operation Funding

Between elections, political money continues flowing:

- Leadership PACs supporting other candidates and building influence

- Party building activities maintaining organizational infrastructure

- Issue advocacy organizations shaping policy debates

- Preparation for future campaigns including early fundraising

Why It’s Important: The Consequences of Campaign Finance Systems

Representation and Access

Campaign finance systems fundamentally shape whose interests receive political attention:

Donor Class Influence: Research consistently shows that policy outcomes align more closely with the preferences of affluent citizens than with those of average citizens. Larry Bartels’ study of US Senate representation found senators’ responses correlated strongly with constituents’ views only in the top third of income distribution.

Access Inequality: The ability to make substantial political contributions typically translates into greater access to elected officials. A 2016 study found that US House members made themselves available to donors nearly four times more often than to non-donors with similar policy interests.

Agenda Control: Financial resources influence which issues receive political attention. Well-funded interests can ensure their preferred issues dominate legislative agendas, while under-resourced constituencies struggle for basic recognition.

Electoral Competition and Outcomes

Money’s impact on election results remains contested but significant:

Financial Advantages: Candidates who outspend their opponents win approximately 80-90% of US House races, though causation versus correlation remains debated. Money appears most decisive in lower-information contests where candidates are less known.

Entry Barriers: High campaign costs can deter qualified candidates from seeking office, particularly those without personal wealth or access to donor networks. This can reduce the quality and diversity of political leadership.

Primary Effects: Financial advantages often prove most decisive in party primaries, where name recognition may be lower and ideological positioning more important. Well-funded candidates can define themselves and their opponents before most voters engage.

Policy Outcomes and Governance

The relationship between money and policy represents the ultimate concern:

Specific Policy Influence: Numerous studies document correlations between contributions and legislative behavior on specific issues. A 2016 analysis found that US representatives’ financial services votes aligned with banking industry contributions, even controlling for party and ideology.

Regulatory Capture: Agencies tasked with regulating industries often develop overly cozy relationships with those they regulate, facilitated by political connections built through campaign support.

Tax and Spending Priorities: Research suggests that campaign finance systems influence broader fiscal policy, with greater private funding associated with lower taxes on high incomes and reduced social spending.

Common Misconceptions and Analytical Challenges

Misconception 1: “Money Buys Elections Directly”

The relationship between spending and electoral success is more complex than often portrayed:

Diminishing Returns: Additional spending yields progressively smaller electoral benefits. The first million dollars spent typically has greater impact than the tenth million.

Quality Matters: How money is spent proves as important as how much is spent. Ineffective advertising or poorly organized field operations waste resources regardless of quantity.

Counter-Spending: Well-funded candidates often face well-funded opponents, potentially canceling financial advantages.

Misconception 2: “All Political Money is Corrupt”

Distinguishing different types of political support is essential:

Constituency Representation: Contributions from individuals within a representative’s district expressing policy preferences differ fundamentally from outside interests seeking special favors.

Ideological Support: Donations based on shared political philosophy rather than specific policy trades represent a legitimate form of political participation.

Small-Donor Democracy: The rise of digital micro-donations enables genuine grassroots funding distinct from traditional large-donor models.

Misconception 3: “Public Financing Eliminates Money’s Influence”

Public funding systems face their own limitations:

Independent Expenditure Circumvention: Outside spending can undermine public systems’ equalizing goals, as demonstrated in US presidential elections post-Citizens United.

Administrative Barriers: Eligibility requirements for public funds may disadvantage insurgent candidates or those without established party support.

Adequacy Challenges: Public funding amounts often fail to keep pace with actual campaign costs, particularly in large jurisdictions.

Recent Developments: Emerging Trends and Innovations

Digital Fundraising Transformation

Technology has revolutionized campaign finance:

Small-Donor Revolution: Digital platforms have dramatically reduced the costs of soliciting and processing small contributions. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns raised over $200 million from more than 2 million individual donors giving an average of $27.

Recurring Contribution Models: Subscription-style political giving enables sustained funding through automated monthly contributions, providing campaigns with predictable cash flow.

Platform-Specific Tools: Social media platforms have integrated fundraising features, while dedicated platforms like ActBlue (Democratic) and WinRed (Republican) have institutionalized digital partisan fundraising.

Transparency and Disclosure Innovations

New approaches aim to illuminate money in politics:

Real-Time Reporting: Some jurisdictions now require more frequent disclosure, with certain states mandating 24- or 48-hour reporting for large contributions close to elections.

Digital Data Standardization: Machine-readable campaign finance data enables more sophisticated analysis by journalists, academics, and watchdog organizations.

Foreign Influence Tracking: Enhanced scrutiny of foreign money has led to more sophisticated analysis of potential circumvention through domestic intermediaries or shell companies.

Global Regulatory Evolution

International approaches continue to develop:

Spending Limit Experiments: Countries like Israel and Mexico have implemented novel approaches to campaign spending restrictions with varying success.

Public Funding Innovations: Germany and Sweden have developed sophisticated public funding systems that balance fairness, competition, and administrative practicality.

Digital Regulation: The European Union and individual member states have begun regulating online political advertising, including transparency requirements for microtargeting and funding sources.

Case Studies: Comparative Campaign Finance Systems

United States: The Market Model

The US system represents the least regulated approach among established democracies:

Legal Framework: The Supreme Court has repeatedly struck down campaign finance regulations on First Amendment grounds, most notably in Buckley v. Valeo (1976) and Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

Current Features:

- No meaningful limits on independent expenditures

- Modest contribution limits to candidates and parties

- Extensive disclosure requirements with significant loopholes

- Limited public funding in presidential elections largely abandoned by major candidates

Consequences:

- Highest campaign costs among democracies

- Extreme donor concentration (0.5% of population provides majority of contributions)

- Extensive independent expenditure operations

- Persistent concerns about corruption and influence peddling

United Kingdom: The Limited Public Funding Model

Britain’s system balances regulation and political freedom:

Legal Framework: Regulated by the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 and overseen by the Electoral Commission.

Key Features:

- Modest public funding through “Short Money” for opposition parties

- Spending limits for candidates and parties

- Reasonable contribution limits with disclosure requirements

- Restrictions on foreign donations

Outcomes:

- Lower campaign costs than US but rising steadily

- Periodic scandals involving wealthy donors and peerages

- Increasing concern about undisclosed digital campaigning

- Generally high public confidence in electoral integrity

Germany: The Public Funding Consensus Model

Germany’s system emphasizes fairness and transparency:

Legal Framework: Governed by Political Parties Act with Constitutional Court oversight ensuring balance between public and private funding.

System Features:

- Extensive public funding matching private donations

- Spending limits for public funding eligibility

- Comprehensive disclosure requirements

- Strict separation between party funding and parliamentary operations

Results:

- Stable party organizations with adequate resources

- Reduced time spent fundraising compared to US counterparts

- Multiple viable parties across ideological spectrum

- High public confidence in political financing system

Conclusion: Key Takeaways and Reform Directions

Synthesized Insights

The global experience with campaign finance reveals several fundamental patterns:

System Diversity Matters: Different regulatory approaches produce significantly different outcomes for representation, competition, and corruption. There is no single “correct” system, but comparative analysis reveals best practices.

Enforcement is Crucial: Well-designed regulations accomplish little without effective enforcement. Independent oversight agencies with adequate resources prove essential for maintaining system integrity.

Adaptation is Constant: As political technology evolves, so must campaign finance regulation. Digital campaigning, new organizational forms, and cross-border money flows require continuous regulatory updates.

Public Funding Can Work: When properly designed, public financing systems can reduce corruption risks, enhance competition, and diminish fundraising pressures on officials.

Future Challenges and Reform Opportunities

Several critical issues will shape campaign finance’s future:

Digital Transparency: Regulating online political advertising and ensuring meaningful disclosure for digital campaigning represents an urgent priority across democracies.

Global Coordination: As political money flows increasingly cross borders, international cooperation on standards and enforcement becomes more necessary.

Small-Donor Empowerment: Systems that amplify small contributions through matching funds or tax credits offer promise for rebalancing political influence.

Constitutional Constraints: In countries with strong free speech protections, designing effective regulations that survive judicial scrutiny remains challenging.

The ongoing struggle to balance political equality, free expression, and democratic integrity through campaign finance systems represents one of the central challenges for 21st-century democracy. As with the evolution of Electoral Systems, the choices societies make about political money will profoundly shape whose voices are heard and which interests prevail in the democratic process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Which countries have the strictest campaign finance regulations?

Norway, Sweden, and Germany have comprehensive systems featuring spending limits, extensive public funding, strict disclosure requirements, and strong enforcement mechanisms.

2. How does Citizens United affect US elections?

The 2010 Supreme Court decision allowed unlimited independent political spending by corporations and unions, leading to massive growth in super PAC and dark money spending.

3. What is the difference between hard money and soft money?

Hard money refers to regulated contributions to candidates and parties, while soft money (now largely banned) referred to unregulated party funds for “party-building” activities.

4. Do campaign contributions directly influence politicians’ votes?

Research shows correlations between contributions and voting patterns, though causation is difficult to establish definitively. The influence often operates through agenda control and access rather than direct vote trading.

5. Which countries provide full public funding for elections?

Several countries including Norway, Sweden, and Costa Rica provide extensive public funding, though most systems combine public and private financing rather than relying exclusively on public funds.

6. How do campaign finance systems affect political polarization?

Some research suggests that small-donor systems may increase polarization by incentivizing appeals to ideological purists, while systems dominated by large donors may produce more centrist politics.

7. What are the most effective campaign finance reforms?

Evidence supports small-donor matching systems, effective disclosure regimes, independent enforcement agencies, and reasonable spending limits as particularly impactful reforms.

8. How does dark money affect political accountability?

When donors are undisclosed, voters cannot hold politicians accountable for their financial connections, undermining democratic accountability and enabling potential corruption.

9. What role do super PACs play in modern elections?

Super PACs dominate presidential and congressional elections in the United States, often spending more than candidates’ own campaigns and fundamentally changing campaign dynamics.

10. How do other democracies prevent foreign election interference?

Most democracies prohibit foreign nationals from making political contributions, though enforcement challenges persist, particularly with digital fundraising and shell companies.

11. What is the impact of campaign finance on voter confidence?

Systems perceived as corrupt or dominated by special interests typically suffer from lower voter confidence and participation, particularly among lower-income citizens.

12. How do digital fundraising platforms affect campaign finance?

Platforms like ActBlue and WinRed have dramatically reduced fundraising costs while enabling small-donor participation, though they may also increase partisan polarization.

13. What are leadership PACs and how do they function?

Leadership PACs allow politicians to raise money to support other candidates, building influence within their party. They operate under different rules than personal campaign committees.

14. How do public financing systems work in practice?

Systems vary from full public funding to partial matching of small donations, with eligibility typically requiring demonstration of public support through signature thresholds or initial fundraising.

15. Where can citizens find information about political donations?

In the United States, the Federal Election Commission website provides searchable databases. Similar agencies in other democracies include the UK Electoral Commission and Elections Canada.