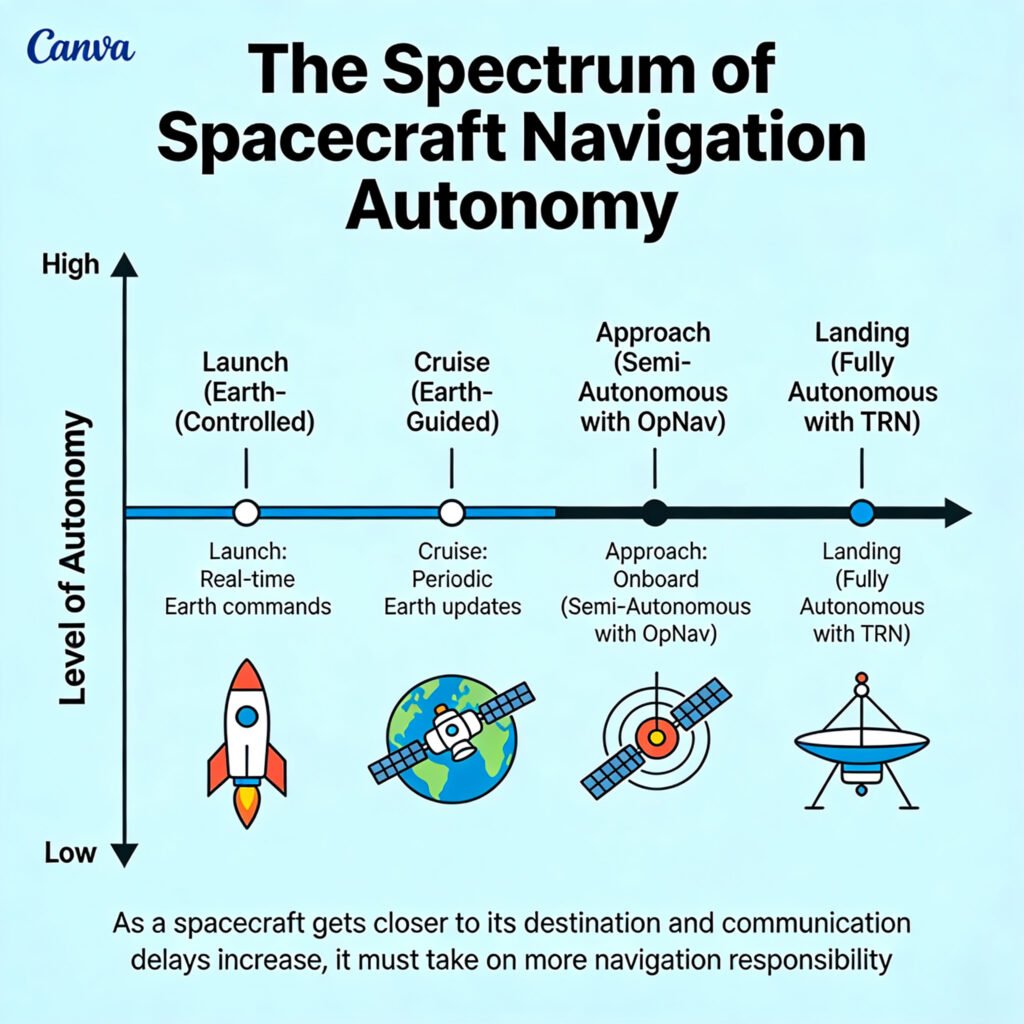

As a spacecraft gets closer to its destination and communication delays increase, it must take on more navigation responsibility.

Introduction – Why This Matters

I was in a control room at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) during the final approach of the Perseverance rover to Mars. The mood was a unique blend of intense focus and helplessness. A monitor displayed the countdown to “entry interface”: 7 minutes. An engineer leaned over and whispered, “Everything you’re about to see already happened 11 minutes ago. The spacecraft is on its own.” In those critical moments—the “seven minutes of terror”—the spacecraft had to execute over 1,000 commands autonomously: adjusting its angle, deploying a parachute at Mach 1.7, using terrain-relative navigation to pick a safe spot, and finally, lowering the rover on cables. All of this happened 140 million miles away, where a signal from Earth takes over 11 minutes for a one-way trip. There is no joystick, no GPS, no do-over.

This is the stark reality of autonomous interplanetary navigation. For curious beginners, it’s the art and science of guiding a robotic explorer across billions of miles of emptiness to a precise spot on a distant, moving target. For professionals, it’s the ultimate challenge in delayed-time robotics, sensor fusion, and decision-making under extreme uncertainty. What I’ve learned from navigators (“navs”) who plot these cosmic voyages is this: The further we go, the smarter our spacecraft must become. In 2025, with missions targeting asteroids, the icy moons of Jupiter, and planning for human voyages to Mars, the era of Earth-reliant, turn-by-turn navigation is over. This article will reveal how AI, computer vision, and atomic clocks are creating a new generation of self-driving spaceships.

Background / Context: From Sextants to Software

Human navigation evolved from following coastlines, to using stars with sextants, to radio beacons, and finally to the Global Positioning System (GPS)—a constellation of satellites providing precise location and time anywhere on Earth. Space navigation has followed a similar, but more extreme, trajectory.

The Earth-Centric Era (1960s-1990s): Early missions like Voyager were navigated almost entirely from Earth. Giant radio antennas of NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) would:

- Send a signal to the spacecraft.

- The spacecraft would return the signal.

- By measuring the round-trip light time (the Doppler shift and delay), engineers could calculate the spacecraft’s radial velocity and distance with incredible accuracy. Its position perpendicular to the line of sight was much harder to determine.

This method, while accurate, had major limitations:

- Latency: Decisions were slow, based on hours- or days-old data.

- Bandwidth: The DSN is a shared, overloaded resource.

- Line-of-Sight: It required the spacecraft to be in view of a DSN antenna.

- Single Point of Failure: The spacecraft was a passive “dumb” terminal.

The shift began with the need for precision landing. Missing Mars by 100 km was okay for an orbiter, but a rover needs to land within a 10 km ellipse, and a sample return mission might need to hit a 50-meter target. This demanded the spacecraft to have “eyes” and a “brain.”

Key Concepts Defined

- Autonomous Navigation: The capability of a spacecraft to determine its own position, velocity, and attitude (orientation) and to execute trajectory corrections without real-time intervention from Earth.

- Optical Navigation (OpNav): Using images of celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, asteroids) taken by an onboard camera to determine the spacecraft’s position relative to those bodies.

- Terrain-Relative Navigation (TRN): A specific type of optical navigation where a spacecraft images the ground during descent, compares it to an onboard map, and determines its location to correct its landing trajectory. Used by Perseverance and SpaceX’s Starship prototypes.

- Delta-Differential One-Way Ranging (Delta-DOR): A highly accurate Earth-based technique where two widely separated DSN antennas receive a signal from the spacecraft. The slight difference in arrival time pinpoints the spacecraft’s position in the sky.

- Star Tracker: An onboard camera that takes images of star fields, compares them to an internal catalog, and determines the spacecraft’s precise orientation (like a high-tech sextant).

- Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU): A suite of accelerometers and gyroscopes that measures changes in velocity and rotation. It’s precise over short periods but drifts over time. It’s the “inner ear” of the spacecraft.

- Cruise Phase: The long coast between planets, where the primary job is to stay on the planned trajectory with occasional correction maneuvers.

- Approach & Landing Phase: The high-stakes period of arrival at a destination, requiring the highest level of autonomy and precision.

How It Works: The Step-by-Step Journey of a Self-Driving Spacecraft

Let’s follow a hypothetical mission to Mars, from launch to landing, to see how autonomy is layered in.

Phase 1: Launch and Cruise – The Celestial Highway

Once a spacecraft escapes Earth’s gravity, it’s on an interplanetary trajectory calculated months in advance.

- Initial State: Position and velocity from launch tracking.

- Primary Navigation (Earth-Based): For the long cruise, the DSN is still the gold standard.

- Ranging: Precisely times a radio signal round-trip.

- Doppler: Measures the frequency shift of the returning signal to calculate velocity along the line ofsight.

- Delta-DOR: Provides a precise “fix” every few weeks to correct for errors perpendicular to the line of sight.

- Onboard Attitude Control: The spacecraft maintains its orientation using:

- Star Trackers: Identify star patterns to know “which way is up.”

- Sun Sensors: Coarse alignment backup.

- Reaction Wheels/Gyros: Spin to adjust orientation without thrusters.

- Trajectory Correction Maneuvers (TCMs): Periodically, the combined Earth data and onboard IMU data indicate a drift. The spacecraft fires its thrusters to get back on course. Later missions can calculate the size and direction of these burns autonomously.

Phase 2: Approach – Switching to Optical Navigation

As the target planet grows from a dot to a disk in the camera, the spacecraft transitions to self-reliance.

- The Problem: Radio signals from Earth give excellent line-of-sight data but poor angular data on the spacecraft’s position relative to the target planet. A tiny angular error from Earth translates to a massive positional error at Mars.

- The Solution: Optical Navigation (OpNav).

- Imaging: The spacecraft’s navigation camera takes pictures of the target planet against a background of stars.

- Processing: An onboard computer runs algorithms to identify the limb (the bright edge of the planet) and the terminator (the line between day and night). It measures the planet’s apparent size and center in the star field.

- Triangulation: By knowing the exact time and the spacecraft’s orientation (from the star tracker), and comparing the observed position of the planet to its predicted position from ephemeris tables (a cosmic almanac stored in memory), the spacecraft can calculate its own position relative to the planet.

- A navigation engineer at JPL described it to me: “It’s like sailing. You measure the angle between the horizon and a star. On a spacecraft, the ‘horizon’ is the limb of Mars, and the ‘stars’ are, well, stars. The computer does the spherical trigonometry in microseconds.”

Phase 3: Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) – The Ultimate Test

This is where full autonomy is non-negotiable. The “brain” must process data and act in seconds, far faster than any signal can reach Earth.

The Perseverance Rover’s Autonomous Descent (2021):

- Atmospheric Entry: Guided by small thrusters to control angle, using only the IMU and pre-loaded models of atmospheric density. No external references yet.

- Parachute Deployment: Triggered autonomously by a radar altimeter measuring velocity and altitude.

- Heatshield Jettison: The Terrain-Relative Navigation (TRN) system activates.

- A downward-facing camera (Lander Vision System) starts taking pictures of the approaching ground.

- The onboard computer (Vision Compute Element) compares these real-time images to a pre-loaded, high-resolution orbital map of the landing zone.

- Using feature matching algorithms (identifying craters, rocks, ridges), it determines the lander’s position to within a few meters.

- Powered Descent & Hazard Avoidance:

- The TRN result is fed to the guidance computer.

- The computer knows the designated safe landing ellipse. If it detects it’s heading for a hazardous area (a large rock field, steep slope), it selects the safest nearby alternative from its map.

- It commands the rocket thrusters to fly to this new, safer target.

- Sky Crane Maneuver: The descent stage hovers, lowers the rover on cables, cuts them, and flies away. All autonomous.

Comparison of Navigation Methods Across Mission Phases

| Mission Phase | Primary Method | Role of Autonomy | Earth’s Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise (Earth to Mars) | DSN Ranging/Doppler, Delta-DOR | Low (Attitude Control, basic TCM execution) | High (Tracking, maneuver calculation) |

| Approach (Near Mars) | Optical Navigation (OpNav) | Medium-High (Self-positioning, updating Earth) | Medium (Providing ephemeris updates, backup) |

| Entry, Descent & Landing | Terrain-Relative Navigation (TRN), Radar, LIDAR | Extreme (Full decision-making & execution) | None (Monitor only) |

The AI & Software Engine

The “intelligence” behind this autonomy is a fusion of classical algorithms and modern AI.

- Classical: Kalman Filters are the unsung heroes. They combine noisy data from multiple sensors (IMU, star tracker, camera) to produce a “best estimate” of the spacecraft’s state, constantly updating as new data arrives.

- Modern AI/ML:

- Computer Vision: For TRN, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can be trained to identify landing hazards (boulders, slopes) faster and more reliably than traditional feature-matching in low-light or dusty conditions.

- Reinforcement Learning: Being tested for optimal guidance during powered descent—learning the most fuel-efficient way to land from a vast number of simulated approaches.

- Anomaly Detection: ML models monitor spacecraft subsystem data to predict failures (e.g., a reaction wheel wearing out) and suggest or execute mitigation before Earth is even aware.

Why It’s Important: Unlocking the Next Frontier

Autonomous navigation is not a convenience; it’s an enabler for everything that comes next in space exploration.

- Enables High-Risk, High-Reward Landings: To land on the icy crust of Europa (Jupiter’s moon) or in the rugged highlands of the lunar south pole, we must land with precision and avoid hazards in real-time. Earth-based control is impossible due to light-time delays (up to 100 minutes for Jupiter).

- Increases Mission Robustness and Science Return: A rover that can autonomously navigate complex terrain (like NASA’s Perseverance using AutoNav) can drive farther and safer, choosing its own path around rocks. This means more science targets visited per day.

- Scales Exploration: For human missions to Mars, pre-deploying cargo and habitat modules will require multiple, precise, autonomous landings. Astronauts cannot manually land multiple heavy payloads.

- Reduces Ground Operations Cost: DSN time is expensive. The more a spacecraft can navigate itself, the less it needs to “phone home” for directions, freeing up the DSN for more missions. It also reduces the size of (and cost for) the ground support team.

- Opens Up New Destinations: To explore small, distant bodies like asteroids or comets, where gravity is weak and the shape is irregular, a spacecraft must be able to autonomously maintain a stable orbit and perform close-proximity operations. The OSIRIS-REx mission’s autonomous “Touch-And-Go” (TAG) sample collection from asteroid Bennu is a prime example.

- Foundation for In-Space Infrastructure: Future on-orbit servicing, refueling, and debris removal all require two spacecraft to rendezvous and dock autonomously. This technology is being proven today by missions like Northrop Grumman’s Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV).

Sustainability in the Future: The Self-Aware Spacecraft Network

The future of space navigation is distributed, cognitive, and networked.

- The Interplanetary Internet: Instead of each spacecraft talking only to Earth, they will relay data through a network. A Mars orbiter could provide navigation beacons for landers (like a Mars GPS), drastically improving their accuracy. NASA’s Mars Relay Network already does this for communications; navigation is the next step.

- Pulsar-Based Navigation: An experimental but profound concept. Millisecond pulsars are neutron stars that emit radio waves with the regularity of an atomic clock. A spacecraft equipped with an X-ray telescope could measure the arrival times of pulses from multiple pulsars to triangulate its position anywhere in the solar system—a truly autonomous, cosmic GPS. The SEXTANT experiment on the ISS has demonstrated this.

- Federated Learning Across Fleets: Imagine a constellation of Mars rovers. Using federated learning, each rover’s AI navigation model learns from its local terrain. These learnings are shared and combined to create a master model that makes every subsequent rover smarter from the moment it lands, without sending terabytes of raw data back to Earth. This collective intelligence is a powerful trend, similar to those discussed in analyses of global affairs and systems.

- AI Copilots for Human Missions: For crewed missions, autonomy will be a safety co-pilot. The AI will monitor trajectory, system health, and landing site hazards in real-time, presenting options and executing emergency procedures if needed, allowing the human crew to focus on mission objectives and decision-making.

Common Misconceptions

- Misconception: “Spacecraft just follow a pre-programmed path like a train on rails.” Reality: The trajectory is a pre-planned reference, but solar radiation pressure, gravitational tugs from small bodies, and thruster imperfections constantly push the spacecraft off course. It’s more like a sailor constantly correcting for wind and current to stay on a charted bearing.

- Misconception: “They use GPS.” Reality: GPS satellites orbit Earth. Their signals are far too weak and geometrically unsuitable for use beyond a few Earth radii. For lunar missions, there are concepts for a Lunar GPS, but it doesn’t exist yet.

- Misconception: “Autonomous means no humans are involved.” Reality: Humans are deeply involved in designing, testing, and simulating every possible scenario. We teach the autonomy how to think. The spacecraft then applies those lessons independently. It’s like training a pilot with thousands of flight simulators before their first solo.

- Misconception: “More autonomy means more risk.” Counterintuitively, it often means less risk. A system that can react in milliseconds to a landing hazard is safer than one waiting 20 minutes for orders from Earth. Autonomy is about managing risk in environments where human reaction time is insufficient.

Recent Developments (2024-2025)

- Lunar GNSS Experiments: In 2024, NASA’s CAPSTONE cubesat and other commercial landers successfully tested using weak, sidelobe signals from Earth GPS satellites to help navigate in cislunar space. This is a game-changer for establishing a reliable lunar transportation system.

- Machine Learning for Rover Driving: Perseverance’s AutoNav system has been upgraded via software, now using ML models to better distinguish between hard rocks and compressible sand, reducing its “thinking” time per drive segment by 50% and increasing its safe driving speed.

- Starship’s Autonomous Flight Tests: SpaceX’s Starship prototypes are advancing the state of the art for large vehicle autonomous landing. Their real-time propulsion and aerodynamic control during the “belly-flop” maneuver is an unparalleled demonstration of onboard guidance for massive vehicles.

- DARPA’s FENCE Project: The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is developing algorithms for autonomous spacecraft to navigate and perform tasks in Geostationary Orbit (GEO) without GPS, using only observations of Earth, the moon, and stars.

- ESA’s JUICE Mission: The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, en route, carries advanced autonomous navigation software to manage its complex tour of the Jovian system, where light-time delays make real-time control from Earth impractical.

Success Story: OSIRIS-REx and the TAG Sample Collection

The OSIRIS-REx mission’s autonomous Touch-And-Go (TAG) maneuver at asteroid Bennu in 2020 is a masterclass in distant autonomy. Bennu is only 500 meters wide, with a gravity field 100,000 times weaker than Earth’s. Pushing too hard would launch the spacecraft away; misaiming could crash it.

- The Challenge: A 18.5-minute light-time delay ruled out real-time control.

- The Autonomous Sequence:

- Descent: The spacecraft left its “safe home orbit” and descended using Natural Feature Tracking (NFT). Its camera matched real-time images of Bennu’s boulder-strewn surface to a high-resolution 3D map, updating its position 8 times per second.

- Hazard Check: At a pre-defined checkpoint, it compared the target site to its hazard map. Had it been off-course, it would have autonomously aborted.

- Contact: It continued, touched the surface for approximately 6 seconds, fired a nitrogen gas bottle to stir up regolith, and captured the sample.

- Back-Away: It immediately fired thrusters to back away safely.

- The Result: A perfect collection of over 250 grams of pristine asteroid material. The spacecraft made hundreds of critical decisions based on its own sensor data, executing a delicate ballet around a tiny, distant rock with zero input from its human controllers during the event. It demonstrated that we can trust robots to perform incredibly complex physical interactions across the solar system.

Real-Life Examples

- For a Mars Orbiter (e.g., MAVEN):

- Uses star trackers and sun sensors for attitude.

- Primarily relies on Earth-based DSN tracking for orbit determination.

- Can perform autonomous momentum management (unloading reaction wheels) and safing responses if it detects an anomaly.

- For a Lunar Lander (e.g., Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus):

- Used optical navigation during transit.

- Employed a hazard-relative landing system during descent, using LiDAR and cameras to map the terrain in real-time and select a safe spot within a target zone.

- For a Deep Space Probe (e.g., Voyager):

- The ultimate example of long-term, low-level autonomy. With communication delays now over 22 hours, it must:

- Automatically adjust its attitude to keep its antenna pointed at Earth.

- Manage its power from decaying radioisotope generators.

- Execute pre-programmed instrument scans.

- Enter and recover from fault protection “safe modes” on its own.

- The ultimate example of long-term, low-level autonomy. With communication delays now over 22 hours, it must:

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Autonomous interplanetary navigation represents a fundamental shift in our relationship with our robotic explorers. We are moving from remote-controlled puppets to capable, intelligent partners. This shift is driven by necessity—the laws of physics that limit the speed of light—and enabled by the exponential growth of computing power and artificial intelligence.

The journey is from tele-operation to tele-presence to tele-intelligence. We are not just extending our eyes and hands into space; we are extending our problem-solving cognition. The spacecraft becomes an embodiment of the mission team’s collective knowledge, sent ahead to act on our behalf.

As we venture to worlds with longer communication delays and more dynamic environments, this autonomy will only deepen. The spacecraft of the future will not just follow a map; it will draw its own.

Key Takeaways Box:

- Light Speed is the Ultimate Limit: Communication delays make Earth-based control impossible for critical maneuvers, forcing autonomy.

- It’s a Multi-Sensor Fusion Problem: No single sensor is enough. Success comes from blending data from star trackers, cameras, IMUs, and radios using sophisticated software like Kalman filters.

- Optics are Key for Precision: For pin-point landings and approaching small bodies, optical navigation (OpNav, TRN) is the only solution.

- AI is the New Co-Pilot: Machine learning enhances hazard detection, path planning, and system health management, making autonomy more robust and efficient.

- We Are Already Living in This Future: Missions like Perseverance and OSIRIS-REx have already executed breathtaking feats of autonomy. This is not speculative; it’s operational.

For more detailed explanations of complex scientific principles, visit our Explained section at The Daily Explainer.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How accurate is interplanetary navigation?

It’s astonishingly accurate. Cruise navigation can predict a spacecraft’s position within a few kilometers over hundreds of millions of kilometers. Landing navigation (with TRN) can deliver a rover to within tens of meters of a target point on another planet.

2. What is a “trajectory correction maneuver” and how is it planned?

A TCM is a small rocket burn to correct the spacecraft’s path. Initially planned on Earth using DSN data, newer missions can calculate the need for and execute smaller TCMs autonomously using their OpNav data. Major TCMs are still planned on Earth.

3. Do spacecraft have maps stored onboard?

Yes. For Terrain-Relative Navigation, a high-resolution orbital map of the landing zone is stored in the spacecraft’s memory. The real-time images are compared to this map. The map is created by orbiters (like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) and uplinked before landing.

4. What happens if the onboard camera fails during descent?

There are layers of redundancy. Perseverance had two identical computer systems for its Vision Compute Element. It also had a less-precise but functional backup system using only the IMU and radar. The spacecraft is designed to “fail operational”—losing one system degrades performance but doesn’t cause a total failure.

5. Can astronauts take control if needed?

For crewed missions, yes, but within limits. During the Apollo landings, astronauts took manual control when they saw the automatic system heading for a boulder field. For future Mars landings, the crew will have override capability, but the primary mode will be fully autonomous due to the complexity and the 4-20 minute communication delay during the final descent.

6. What is “safing” mode?

An autonomous fault-protection routine. If the spacecraft’s software detects an anomaly it can’t resolve (e.g., losing star lock, unusual temperature), it will put itself in a stable, power-safe configuration, point its antenna at Earth, and wait for instructions. This has saved many missions.

7. How do you test autonomous navigation software before launch?

Extensively in simulation. Teams build “Mars Yards”—rocky terrain test beds for rovers. For landing, they use “field tests” with helicopters or high-altitude balloons that drop prototype landers. The software runs millions of Monte Carlo simulations, varying every possible parameter (wind, thruster performance, sensor noise) to ensure robustness.

8. What is the role of the Deep Space Network (DSN) in autonomous missions?

It remains vital. The DSN is the communication backbone for sending software updates, receiving science data, and providing the backup navigation data that the spacecraft’s autonomous systems use to cross-check themselves. It’s the link that allows the “autonomy loop” to include human learning and updates.

9. How does navigation differ for an asteroid vs. a planet?

Asteroids have negligible gravity and irregular shapes, making “orbits” unstable. Navigation relies heavily on optical feature tracking—the spacecraft must constantly image the asteroid and use those features as markers to maintain its position, often in a “station-keeping” hover rather than a true orbit.

10. Is there an “autopilot” button?

Not really. Autonomy is layered into different phases and functions. A command from Earth might be: “Execute the landing sequence,” which kicks off a chain of thousands of autonomous actions. Or for a rover: “Drive to that rock,” and the rover’s AutoNav handles the pathfinding and driving.

11. How do you account for the gravity of other planets during cruise?

Gravity is the map. Mission designers use precise ephemeris models of the solar system—the calculated positions and masses of all major bodies. The spacecraft’s intended trajectory is a solution to a complex multi-body gravity problem. During flight, small errors are corrected with TCMs.

12. What is “celestial mechanics” in this context?

The branch of physics that predicts the motion of spacecraft under the influence of gravitational forces. It’s the foundation of all trajectory design. Autonomous systems don’t re-derive celestial mechanics; they use pre-loaded models and make small corrections based on where they actually are versus where the models say they should be.

13. Could a solar flare or radiation burst disrupt navigation?

Yes. A severe event could cause single-event upsets (SEUs)—bit flips in the computer’s memory. Spacecraft hardware is “radiation-hardened,” and software has error-checking and recovery routines. A critical system might have triple redundancy: three computers vote on every decision; if one disagrees, it’s reset.

14. How does the mental model of autonomous navigation compare to running a complex remote business?

The parallels are profound. Both involve: Setting a clear goal (landing site/business outcome), establishing a plan (trajectory/business plan), deploying automated systems (spacecraft AI/software automation), monitoring from a distance with latency (DSN data/quarterly reports), and intervening only for major strategic corrections (TCMs/board decisions). It’s the ultimate exercise in trust and system design, principles explored in resources like Sherakat Network’s blog on operational excellence.

15. What is “pseudo-range” in space navigation?

A technique where a spacecraft listens to signals from multiple DSN antennas on Earth. By measuring the time difference of arrival (like a cosmic version of cell phone triangulation), it can calculate its own position without needing the two-way ranging delay. This gives it a faster position fix.

16. Will quantum computing help with space navigation?

Potentially, in the long term. Quantum sensors could make incredibly precise measurements of acceleration and rotation, reducing IMU drift. Quantum computers could solve optimal trajectory problems (like multi-stop asteroid tours) in seconds that take classical computers weeks.

17. How do you navigate when you can’t see stars (e.g., in daylight on a planet)?

During a Martian daytime landing, the navigation camera can’t see stars. It relies on the IMU for orientation during the final seconds, fed by the last known position from TRN. For rovers driving in daylight, they use visual odometry: comparing camera images between wheel turns to measure distance traveled and correct for wheel slippage.

18. What is the most difficult autonomous navigation challenge attempted so far?

Arguably, the OSIRIS-REx TAG maneuver or the Perseverance landing with TRN. Both required sub-meter precision in dynamic, low-gravity environments with zero real-time human input. The upcoming Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s moon Titan will face a new challenge: autonomous navigation in a thick atmosphere with organic haze, using rotorcraft.

19. Is there a risk of the AI making a “wrong” decision?

Yes, which is why the autonomy is bounded and tested exhaustively. It’s not a general AI. It’s a set of algorithms designed for specific scenarios. The “decision space” is constrained (e.g., “choose the safest spot within this 1km area”). Wrong decisions are usually due to un-modeled environmental factors (e.g., dust storm), not rogue AI.

20. How do you update the software on a spacecraft years into its mission?

Carefully. Software updates are packaged into commands, transmitted via the DSN, and loaded into non-volatile memory. The spacecraft reboots into the new software. This is done for bug fixes, performance improvements, or to add new capabilities (like Perseverance’s improved AutoNav). It carries inherent risk, so it’s done only after extensive ground testing.

21. What role do universities and nonprofits play in this field?

A huge role. Universities (like MIT, Stanford, UT Austin) conduct foundational research in guidance algorithms and AI. Nonprofits like The Planetary Society advocate for and help fund technology demonstrations. The collaborative, mission-driven ethos seen in the nonprofit hub is alive and well in space science.

22. Can this technology be used on Earth?

Absolutely. The sensor fusion and state estimation algorithms (Kalman filters) are used in self-driving cars, drones, and submarines. Terrain-relative navigation inspired some early GPS-denied navigation for military aircraft. The extreme requirements of space drive innovation that often trickles down.

23. Where can I see real-time data from spacecraft?

NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System is a fantastic interactive simulation. The DSN Now website shows which spacecraft the network is currently talking to. For mission-specific data, check the websites of NASA JPL or ESA.

About the Author

Sana Ullah Kakar is an aerospace software engineer and former flight dynamics analyst. They spent several years working on the orbit determination and maneuver planning teams for planetary missions, which gave them a deep appreciation for the intricate dance between human planning and machine execution in the void. They have a passion for explaining the “hidden” software that makes space exploration possible—the millions of lines of code that act as the spacecraft’s instincts. At The Daily Explainer, they believe that understanding autonomy demystifies our future in space, showing it as a testament to human ingenuity rather than magic. When not tracing orbital paths, they can be found hiking with a high-precision GPS unit, pondering how different—and yet fundamentally similar—navigation is on Earth and off it. Reach out with questions via our contact page.

Free Resources

- NASA JPL Navigation and Mission Design Section: Technical publications and overviews of navigation techniques.

- NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System: An incredible 3D visualization tool to see where missions are in real-time.

- “Deep Space Chronicle” by NASA History Division: A comprehensive history of robotic planetary exploration, including navigation challenges.

- The Interplanetary Network Progress Report (IPN PR): Technical reports from JPL on deep space communications and navigation (for advanced readers).

- SPICE Toolkit (NASA): The fundamental software used by scientists and engineers to compute spacecraft position and orientation. Its educational materials are a deep dive into the mechanics.

- Related Analysis: For insights into how such complex projects are managed and funded, explore discussions on global affairs and policy shaping space exploration.

Discussion

Would you trust a fully autonomous system to land a crewed spacecraft on another world, or should humans always have final override control? What destination (Europa’s ocean, Venus’s clouds, a fast-moving comet) do you think presents the greatest autonomous navigation challenge? Share your thoughts on the balance between human judgment and machine precision in the comments below.