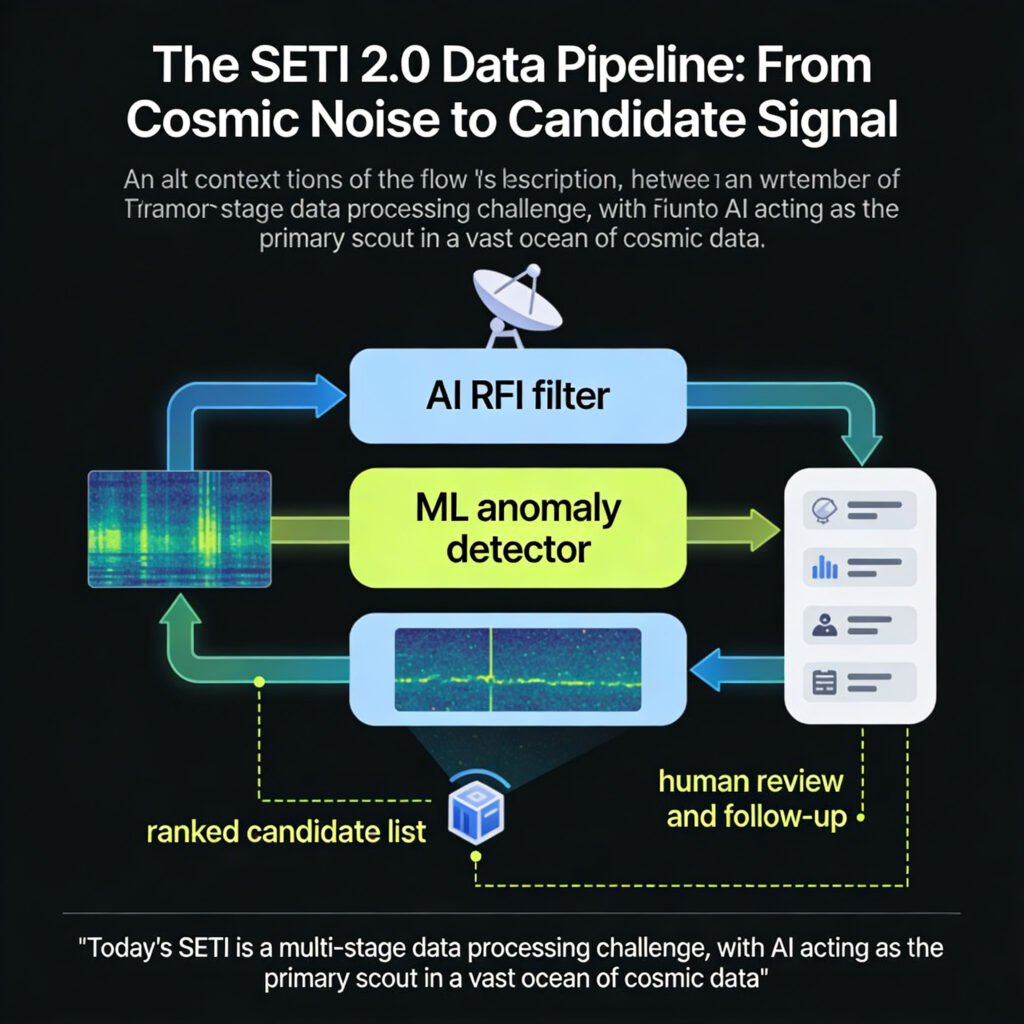

Today's SETI is a multi-stage data processing challenge, with AI acting as the primary scout in a vast ocean of cosmic data.

Introduction – Why This Matters

I was standing under the colossal dish of the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the largest fully steerable radio telescope on Earth. The air was crisp, and the silence was profound, broken only by the hum of distant electronics. The project scientist gestured toward the sky. “Right now,” she said, “we’re collecting 200 gigabytes of data per second from a tiny patch of sky. Hidden in that waterfall of cosmic noise could be a single, structured pulse—a ‘hello’ from a civilization a thousand light-years away. Finding it isn’t a needle in a haystack. It’s a specific grain of sand, on a specific beach, on a planet we haven’t discovered yet.” This is the monumental challenge—and breathtaking promise—of the modern Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). And in 2025, the entire endeavor is being supercharged by artificial intelligence.

For curious beginners, SETI might evoke images of giant ear-shaped antennas listening for alien radio. For professionals, it’s a data science problem of staggering proportions, now colliding with the AI revolution. What I’ve learned from data engineers at the SETI Institute and astronomers at Berkeley is this: The old paradigm of humans staring at waterfall plots is dead. The new paradigm is machines learning the language of the cosmos to spot the one utterance that doesn’t belong. This article will explore how machine learning, along with new types of telescopes and a broader search for “technosignatures,” is creating SETI 2.0—a more powerful, systematic, and intellectually vibrant hunt than ever before.

Background / Context: From Project Ozma to the Data Deluge

The modern SETI era began in 1960 with Project Ozma, led by Frank Drake. Using a radio telescope, he listened to two nearby stars for several weeks. The scale was humble, the technology simple. This established the core method: scan the radio spectrum for narrowband signals that are unlike any known natural phenomenon.

For decades, progress was limited by:

- Telescope Time: Large telescopes are oversubscribed. SETI was often a “parasitic” or secondary activity, piggybacking on other astronomy projects.

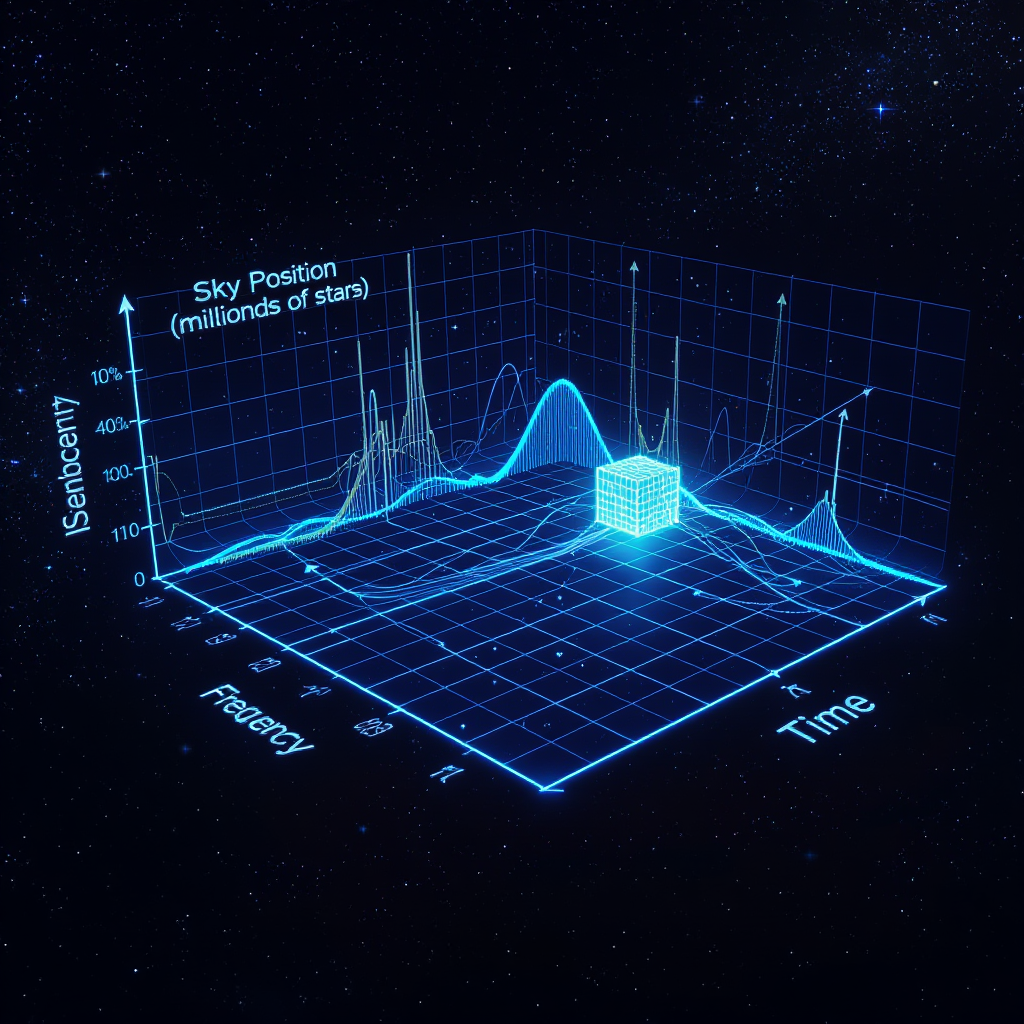

- Limited Search Space: We could only look at a few stars, at a few frequencies, at a few moments in time. The “Cosmic Haystack” (a multidimensional space of frequency, sky position, signal type, and time) was largely unexplored.

- Primitive Signal Processing: Analysts used basic algorithms to flag potential signals, but the final step always involved a human looking at a plot. The human brain is great at pattern recognition, but it gets tired and can only process so much.

The 21st century brought a dual explosion:

- The Exoplanet Revolution: The Kepler and TESS missions proved that planets are common. We now know of over 5,500 exoplanets, with billions estimated in our galaxy alone. This provided SETI with a vast new target list—we now know where to look.

- The Data Deluge: New radio telescopes like the Allen Telescope Array (ATA) and repurposed instruments like MeerKAT produce petabytes of data. The upcoming Square Kilometre Array (SKA) will generate data at a rate exceeding the entire global internet traffic. Humans cannot analyze this. Only AI can.

This created a crisis and an opportunity. SETI 2.0 was born from the necessity to mine these new data mountains, and it is defined by three pillars: dedicated instruments, AI/ML analysis, and the expansion beyond radio to “technosignatures.”

Key Concepts Defined

- SETI: The collective term for scientific searches for intelligent extraterrestrial life, by analyzing electromagnetic radiation or other indicators for signs of technology.

- Technosignature: Any measurable property or effect that provides scientific evidence of past or present technology. This is broader than a deliberate radio beacon and includes things like city lights on exoplanets, atmospheric pollution, megastructures, or even industrial heat signatures.

- Radio SETI: The traditional search for artificial, narrowband radio signals. These are attractive because radio waves travel efficiently through space and our galaxy, and a narrowband signal is easily distinguishable from natural broadband cosmic noise.

- The “Waterfall Plot”: A standard visualization in radio SETI. Time runs left to right, frequency runs top to bottom, and signal strength is represented by color. A persistent, narrowband artificial signal appears as a vertical line.

- Fast Radio Burst (FRB): A mysterious, millisecond-duration burst of radio waves from deep space. Most are likely natural (e.g., from magnetars), but their precise, powerful nature makes them interesting SETI candidates. Could some be engineered?

- Breakthrough Listen: A $100 million, decade-long SETI program launched in 2015. It buys massive amounts of dedicated telescope time on world-class instruments and applies state-of-the-art signal processing and machine learning to the data.

- The “Wow! Signal”: A famous, strong, narrowband radio signal detected in 1977. It was never repeated and remains the best candidate for a potential extraterrestrial signal, though its origin is still unconfirmed.

- Biosignature vs. Technosignature: A biosignature (like atmospheric oxygen and methane together) suggests life. A technosignature suggests intelligent, technology-using life.

How It Works: The AI-Powered SETI Pipeline

Let’s follow a stream of radio waves from a distant star system through the modern SETI detection pipeline, from telescope to potential discovery.

Step 1: Data Acquisition – The Cosmic Snare

- The Telescope: A dedicated array like the Allen Telescope Array (ATA) or a shared facility like the Green Bank Telescope (GBT) or MeerKAT is pointed at a target list. Breakthrough Listen has surveyed over 1,000 nearby stars and 100 galaxies.

- The Raw Data: The telescope doesn’t “hear” sounds. It measures the intensity of electromagnetic radiation across a wide range of frequencies, digitizing it into a torrent of complex numbers. A single observation can produce petabytes of data.

Step 2: Pre-processing & RFI Mitigation – Cleaning the Canvas

This is the first and most critical filter. Over 99.999% of detected signals are Radio Frequency Interference (RFI) from human technology.

- Common RFI Sources: GPS satellites, aircraft radar, cell phones, car ignitions, even microwave ovens in the observatory kitchen.

- Traditional Filtering: Uses algorithms to flag signals that match known RFI patterns (e.g., coming from the horizon, drifting in frequency like a satellite, or matching a known terrestrial frequency).

- AI-Enhanced Cleaning: Machine learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are now trained on millions of examples of RFI. They can identify and remove complex, novel, or intermittent RFI that rule-based systems miss. They learn the “fingerprint” of human noise.

Step 3: Candidate Signal Identification – The AI Scout

This is where the core search happens. The clean data is scanned for signals that match an “interesting” profile.

- Traditional “Match Filtering”: Algorithms look for the classic narrowband signal—a persistent tone. They produce a list of “hits” (candidate signals).

- The ML Revolution – Learning What’s “Weird”: Modern systems use unsupervised and semi-supervised machine learning.

- The AI is fed vast amounts of known data: pure noise, known RFI, and simulated artificial signals.

- It learns a model of “normal” background cosmic noise and terrestrial interference.

- It then scans new data and flags anomalies—anything that statistically deviates from this learned model of normality.

- This is key: Instead of just looking for a narrowband signal, it can flag any unusual structure: a burst with a strange frequency sweep, a repeating pattern with prime-number intervals, or a signal that appears only when the telescope is pointed at a specific star and disappears when pointed away (the “on-off” test). As Dr. Steve Croft, a Breakthrough Listen project scientist, told me: “We’re not just looking for a spike. We’re asking the AI, ‘What’s the weirdest thing in this data?’ That’s often where the most interesting science—SETI or otherwise—is hiding.”

Step 4: Prioritization & Classification – Triage

Even after cleaning, a single observation can generate tens of thousands of candidate signals. Human review is the bottleneck.

- AI-Powered Triage: A second layer of ML models ranks candidates by their “interestingness.” It learns from past human reviews which features (signal-to-noise ratio, frequency stability, coincidence with target star) make a candidate worth a human’s time. This can reduce the list for human review by 99%.

- Citizen Science: Projects like SETI@home (now retired) and its successor Universe@home use distributed computing. Newer initiatives are exploring ways for citizen scientists to train and validate ML models or examine AI-pre-sorted candidates.

Step 5: Follow-up & Verification – The Gold Standard

A single detection means nothing. The standard is repeatability and localization.

- Re-observation: Point the telescope at the same coordinates again. Does the signal reappear?

- Multi-site Verification: Can another, geographically distant telescope (to rule out local RFI) also detect it?

- “On-Off” Testing: Does the signal disappear when the telescope points slightly away from the target? This is the most powerful test for an extraterrestrial origin.

The Modern SETI 2.0 Pipeline Diagram:

(Conceptual Canva Graphic Description)

A flowchart showing: Telescope Data → RFI Mitigation (AI Filter) → Anomaly Detection (ML Scout) → Candidate Ranking (AI Triage) → Human Review → Follow-up Observations.

Why It’s Important: More Than Just “Finding Aliens”

A successful SETI detection would be the most profound discovery in human history, reshaping our understanding of our place in the cosmos. But even the search itself delivers immense value:

- Driving Frontier Data Science: The techniques developed for SETI—especially for RFI mitigation and anomaly detection in massive datasets—are directly applicable to radio astronomy, planetary radar, and satellite tracking. SETI pioneers tools that the entire astronomy community later adopts.

- Exploring the Parameter Space of “Life”: SETI forces us to think rigorously about what intelligence and technology are, how they might manifest across the universe, and how we might recognize them. It’s a foundational exercise in astrobiology and cognitive science.

- Catalyzing Telescope and Instrument Development: The need for dedicated SETI time led to the construction of the Allen Telescope Array. The computational demands of SETI push the development of high-performance computing and data storage solutions.

- A Unifying Human Endeavor: SETI is one of the few truly global, apolitical scientific pursuits. It captures the public imagination and inspires generations to pursue STEM fields. It embodies the human trait of curiosity.

- The “Beneficial Brain” Effect: The process of searching for extraterrestrial intelligence inevitably leads us to study and understand our own planet’s technosphere better. Monitoring our own “leakage” (TV, radar) teaches us about the detectability of civilizations, a topic with implications for everything from privacy to energy efficiency, connecting to broader discussions on global systems.

Sustainability in the Future: The Omni-Spectral, Continuous Search

The future of SETI is multi-messenger, continuous, and embedded.

- Optical and Infrared SETI: Searching for pulsed laser signals or the waste heat of advanced civilizations (Dyson sphere infrared excess). Instruments like the VERITAS gamma-ray telescope are being used for optical SETI searches.

- The “SETI Engine” as a Standard Feature: Future giant telescopes like the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) will have real-time SETI processing pipelines baked into their data flow from day one. SETI won’t be a piggybacker; it will be a primary science driver.

- Exoplanet Atmosphere Technosignatures: The next generation of space telescopes (Habitable Worlds Observatory) will analyze the atmospheric spectra of Earth-like exoplanets. ML will scour these spectra not just for biosignatures (oxygen), but for technosignatures like industrial pollutants (CFCs), artificial greenhouse gases, or even the spectral signature of large-scale photovoltaic arrays (solar farms).

- Neural Networks that Dream of Signals: Using generative AI and simulation-based inference, we will create vast synthetic datasets of every conceivable type of signal from natural and technological sources. ML models trained on this universe of simulations will be hyper-sensitive to any real signal that matches any technological hypothesis.

- The Search for Artifacts (SETA): Looking for physical evidence in our own solar system—an old probe in orbit, mining debris on an asteroid. This “archaeology” approach is gaining traction as we explore the solar system more thoroughly.

Common Misconceptions

- Misconception: “SETI has failed because we haven’t found anything.” Reality: This is the “SETI Paradox” or “Great Silence.” The truthful answer is: We have barely begun to search. As astronomer Jill Tarter famously analogized, if the total searchable cosmic haystack were equivalent to all the water in Earth’s oceans, the cumulative searches to date have examined about a glass of water. AI is finally letting us take bucket-sized scoops.

- Misconception: “Aliens would use radio; it’s obsolete.” Reality: Radio is not obsolete; it’s fundamental. It remains the most efficient way to send information across interstellar distances with minimal energy loss. An emerging civilization might discover radio physics just as we did. We search for radio not because it’s what we would use, but because it’s a universal, efficient technology likely discovered by any electromagnetic-aware civilization.

- Misconception: “A positive signal would be obvious, like a message in English.” Reality: The first signal we detect is most likely to be a beacon—a simple, powerful “we are here” signal, not a complex message. Decoding any potential message would be a separate, monumental challenge. The initial discovery would simply be the recognition of an artificial pattern.

- Misconception: “Governments are hiding evidence.” Reality: The global scientific community is extraordinarily open. Data from Breakthrough Listen is public. Discovering ETI would be the crowning achievement of any scientist’s career—it is not in anyone’s interest to hide it. The “signal-to-noise” problem is real; conspiracy is not needed to explain the lack of a detection.

Recent Developments (2024-2025)

- The “BLC1” Follow-up & Lessons Learned: The 2020 candidate signal from Proxima Centauri (BLC1) was ultimately attributed to human technology, but the process was a watershed. It demonstrated a modern, rigorous verification pipeline and highlighted the critical need for even better RFI rejection—a problem now being attacked with next-generation ML models.

- Breakthrough Listen’s MeerKAT Results: In 2024, the team published the first results from using South Africa’s MeerKAT array as a SETI instrument. Its interferometric capabilities allow for extremely precise localization of signals, instantly ruling out any RFI not coming from the exact direction of the target star. They scanned over 1.3 million stars with unprecedented sensitivity.

- AI Discovers New Fast Radio Burst Patterns: ML algorithms applied to FRB data have uncovered new sub-classes and repeating patterns that human analysts missed, reinvigorating the debate about their origins and keeping the door open to the remote possibility of an artificial source for some.

- Technosignature Workshops Go Mainstream: NASA and other agencies now regularly host joint biosignature and technosignature workshops, formally integrating the search for intelligent life into the broader astrobiology roadmap. Technosignatures are no longer a fringe concept but a legitimate branch of astronomy.

- Open-Source SETI Tools: Projects like BLIP (Breakthrough Listen Intermediate Processor) and TURBO are making state-of-the-art SETI data processing pipelines available to the public and smaller research institutions, democratizing the search.

Success Story: The Allen Telescope Array (ATA) – A Dedicated Ear

The Allen Telescope Array, funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, is the embodiment of the SETI 2.0 philosophy. Its success isn’t a single detection, but its existence and operational model.

- What it solved: The “telescope time” problem. The ATA is dedicated 24/7 to SETI and radio astronomy. It can stare at targets for days, monitor thousands of stars simultaneously, and react quickly to follow up on candidates.

- Its design: Instead of one giant dish, it uses 42 smaller dishes (with plans for more). This provides a wide field of view and allows for innovative signal processing. It’s also in a protected radio quiet zone.

- The result: It has conducted the most comprehensive SETI survey to date. While it hasn’t found ETI, it has rigorously excluded the presence of certain types of powerful transmitters from a vast number of star systems, steadily narrowing the search space. It proved that a dedicated, scalable, and technologically advanced SETI observatory is not only possible but essential. It serves as a testbed for the ML algorithms now being deployed on larger telescopes.

Real-Life Examples

- For a Nearby Star (e.g., Tau Ceti):

- Breakthrough Listen uses the Green Bank Telescope to observe it across a wide frequency range for 8 hours.

- The raw data is filtered by an ML model trained on Tau Ceti’s previous observations and local RFI maps.

- An unsupervised anomaly detection algorithm flags a narrowband signal at 4.462 GHz that drifts perfectly to compensate for Earth’s rotation (a hallmark of an extraterrestrial source).

- The candidate is ranked #1 by the triage AI and sent to a human analyst.

- The analyst requests immediate re-observation with the ATA and the Parkes Telescope in Australia. Verification begins.

- For an Exoplanet System (e.g., TRAPPIST-1):

- The James Webb Space Telescope takes a spectrum of the atmospheres of its rocky planets.

- Alongside searching for biosignature gases, a specialized ML model scans for unusual, narrow absorption lines that could correspond to an artificial compound like a refrigerant (CFC-11).

- A statistically significant detection is made on the outermost rocky planet. It becomes a prime target for follow-up with next-generation telescopes.

- For a Galactic Survey:

- The MeerKAT array scans the galactic plane not for narrowband signals, but for broadband “leakage”—the collective radio noise from millions of civilizations, analogous to Earth’s radio “smog.” An AI is trained to recognize the statistical fingerprint of such a background against the natural galactic radio background.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

SETI is undergoing a renaissance. It is shedding its image as a quixotic, sporadic hunt and maturing into a rigorous, data-intensive, and multidisciplinary field of observational astronomy. The integration of machine learning is not just an upgrade; it’s a paradigm shift, transforming the search from a question of telescope size to a question of computational intelligence.

The odds of success remain unknown. But for the first time, we are building the tools that give us a fighting chance to explore those odds empirically. We are moving from guessing to knowing, from hoping to systematically investigating.

Whether we find a signal in ten years or ten thousand, the search itself ennobles us. It represents humanity at its most curious, collaborative, and humble—casting a net of questions into the cosmic ocean, eager to learn not just about who else might be out there, but about who we are in the silence.

Key Takeaways Box:

- Data is the New Telescope: The limiting factor is no longer collecting signals, but intelligently processing the exabytes of data we already collect.

- AI is the Indispensable Partner: Machine learning, particularly anomaly detection, is the only tool capable of searching the vast, multi-dimensional “cosmic haystack” for both expected and wholly unexpected signals.

- Technosignatures Expand the Hunt: The search now includes signs of technology in optical, infrared, and atmospheric data, not just radio waves.

- Dedicated Instruments are Critical: Facilities like the Allen Telescope Array provide the continuous, flexible observation time needed for serious SETI science.

- The Search Has Barely Begun: We have explored a minuscule fraction of the possible search space. SETI 2.0 is about scaling up that exploration by orders of magnitude.

For more clear explanations of complex scientific frontiers, continue exploring our library at The Daily Explainer’s Explained section.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What frequencies do SETI scientists listen to?

The “water hole” is a traditional target—the frequencies between the hydrogen line (1420 MHz) and the hydroxyl line (1660 MHz). These are quiet regions of the radio spectrum, and H and OH together form water, a symbol of life. However, modern searches scan billions of channels across a wide range, from ~1 GHz to 10+ GHz, where the galactic background noise is low.

2. How far away could we detect a signal similar to Earth’s TV leakage?

Not very. Our own strongest intentional transmitters (like planetary radar) could be detected by a similar instrument across perhaps tens of light-years. Our unintentional leakage (TV, FM radio) becomes indistinguishable from background noise within less than a light-year. This means Earth has been radio-quiet for most of its history and only recently became briefly “loud.”

3. What would we do if we actually found a signal?

There is a formal, internationally agreed-upon protocol, the “Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence.” Key steps: verify the detection confidentially, inform other observatories for confirmation, inform the United Nations and world governments, and not respond before an international consultation. The protocol emphasizes transparency and peaceful intent.

4. Why don’t we just send messages (Active SETI or METI)?

This is highly controversial. Many scientists, including the late Stephen Hawking, caution against actively broadcasting our location, citing potential unknown risks from a more advanced civilization. Others argue it’s harmless or even ethical to reach out. Currently, Active SETI is done by small groups, not as official policy. The debate is ongoing.

5. Can AI differentiate between a natural pulsar and an alien beacon?

Yes, that’s one of its strengths. Pulsars have very specific physical signatures: they slow down predictably over time, have characteristic pulse shapes, and emit across a wide spectrum. An ML model trained on thousands of pulsar signals would recognize these features. An artificial beacon might have too-perfect frequency stability, an encoded pattern, or other non-natural characteristics.

6. What are “Dyson spheres” and how would we find them?

A hypothetical megastructure built by an advanced civilization to capture most of a star’s energy. It would block visible light but re-radiate the energy as waste heat in the mid-infrared. Searches look for stars with excess infrared emission that can’t be explained by dust. Several candidate stars have been flagged by astronomical surveys and are being studied.

7. How does SETI relate to the study of UFOs/UAPs?

Mainstream SETI is distinct. It uses rigorous, reproducible scientific methods to search for evidence of intelligence at interstellar distances. The study of Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAP) is concerned with objects in Earth’s atmosphere or near-space, a different domain with different evidentiary standards. While both involve unknowns, the methods, scales, and communities are largely separate.

8. What is the “Fermi Paradox” and how does SETI address it?

The Fermi Paradox asks: “If the universe is so vast and old, where is everybody?” SETI is the primary empirical effort to address it. Every star system we search and find empty of powerful transmitters is a data point that helps constrain solutions to the paradox (e.g., perhaps advanced civilizations are rare, short-lived, or choose not to broadcast).

9. How can the public get involved?

- Donate: Support the SETI Institute or Breakthrough Initiatives.

- Participate: Join distributed computing projects or citizen science platforms that involve classifying astronomical data.

- Educate: Learn about the science and share it. Public support is crucial for funding and telescope time.

10. What’s the most common type of false positive?

Satellites. Thousands of satellites, especially in new mega-constellations, transmit in radio frequencies. They create signals that drift in frequency as they move relative to the telescope, mimicking the Doppler shift of an extraterrestrial source. Sophisticated orbital prediction models are now a core part of RFI filtering.

11. Could an AI make a discovery without human understanding?

Potentially, it could flag a signal so bizarre that its artificial nature is statistically clear, even if we don’t understand its “purpose” or encoding. The discovery would be: “An artificial source of unknown function has been detected.” Interpretation would follow.

12. How does quantum computing fit into SETI’s future?

Quantum computers could revolutionize the signal processing step. They could perform Fourier transforms and correlation analyses on massive datasets exponentially faster, allowing for real-time analysis of wider bandwidths and more complex signal types.

13. Are we looking for signs of intelligence or just technology?

Technosignatures are a proxy for intelligence. We search for technology because it’s measurable over interstellar distances. The intelligence behind it is inferred. Some searches also consider modifying the definition to look for signs of large-scale “cosmic engineering” that might not be communicative.

14. What’s the role of universities in SETI?

Critical. Universities like UC Berkeley, Harvard, Penn State, and Oxford host leading SETI research groups. They train the next generation of scientists, develop algorithms, and often lead analysis for projects like Breakthrough Listen. It’s a vibrant academic field.

15. How does the mental and philosophical challenge of SETI compare to other grand projects?

It is unique in its blend of deep technical rigor and profound existential weight. It requires the patience of an archaeologist, the data skills of a Silicon Valley engineer, and the imagination of a philosopher. Maintaining optimism and rigor in the face of a null result is a psychological discipline in itself, not unlike the perseverance needed in other long-term ventures, including entrepreneurial pursuits driven by vision.

16. What is “optical SETI”?

Searching for brief, powerful pulses of laser light. A civilization might use pulsed lasers for interstellar communication because they can pack a lot of data into a tight beam visible over great distances. Telescopes equipped with fast photometers look for nanosecond-scale flashes.

17. Could we find ancient, dead civilizations?

Possibly through “interstellar archaeology.” A dead civilization might leave behind dormant probes, megastructures, or atmospheric technosignatures that persist long after they’re gone. The search for Dyson spheres could fall into this category.

18. How do you simulate alien signals for AI training?

Researchers create synthetic datasets with injected signals that have a wide range of parameters: different bandwidths, modulation types (pulses, frequency sweeps), repetition patterns, and levels of noise. The AI learns to find these amidst real background noise and RFI.

19. What is the “Wow! Signal” and could it have been aliens?

Detected in 1977 at Ohio State University, it was a strong, narrowband signal that matched the expected signature of an extraterrestrial origin. It lasted 72 seconds and was never heard again. While tantalizing, the lack of repetition means it cannot be verified. Most scientists attribute it to a highly unusual but natural event or a reflected piece of human-generated RFI.

20. How does SETI funding work?

It’s a mix of private philanthropy (e.g., Paul Allen, Yuri Milner’s Breakthrough Initiatives), small government grants (from NASA’s astrobiology program), and university research funds. It is not a large, sustained government program like particle physics or planetary science.

21. Could a signal be hidden in something we see every day, like cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation?

It’s a creative idea, but unlikely. The CMB is a nearly perfect blackbody spectrum from the early universe. Embedding a message in it would require manipulating the universe itself on a vast scale. Simpler, more energy-efficient methods (like a focused radio beam) are more probable.

22. What’s the single biggest need for advancing SETI?

More dedicated telescope time on world-class instruments. AI can analyze the data, but it needs data to analyze. Long-term, consistent access to facilities like the SKA or the next generation of optical telescopes is the key to a thorough search.

23. Where can I access real SETI data or see results?

- Breakthrough Listen Open Data Archive: Hosts petabytes of processed data for public download.

- SETI Institute Website: Publishes research papers and news.

- Technosignature literature on arXiv.org (search for “technosignature” or “SETI”).

About the Author

Sana Ullah Kakar is a data journalist and former radio astronomy researcher. They have a background in signal processing and have worked on projects analyzing data from atmospheric probes and early radio telescopes. This experience gave them a deep appreciation for the challenge of finding meaningful patterns in cosmic noise. They are fascinated by SETI not only as a scientific endeavor but as a cultural and philosophical project—a mirror we hold up to the universe to see our own reflection. At The Daily Explainer, they are committed to translating the complex, data-driven work of modern SETI into compelling narratives about curiosity, perseverance, and the human spirit. When not writing, they can be found with amateur radio equipment, listening to the static between stations, wondering what else might be riding the waves. Connect with us via our contact page.

Free Resources

- Breakthrough Listen Open Data Archive: The largest public repository of SETI data in the world.

- SETI Institute’s “Big Picture Science” Podcast: Engaging, accessible discussions on SETI and general science.

- NASA Technosignatures Workshop Reports: Found on NASA’s technical reports server, these are the blueprints for the future of the field.

- “The SETI Equation” Interactive Website: Play with the parameters of the famous Drake Equation to see how estimates of intelligent civilizations change.

- Software: Get involved with open-source tools like BLIP or SETI@home code repositories to understand the processing pipelines.

- Related Big-Picture Thinking: For perspectives on how humanity tackles other existential questions and builds collaborative knowledge, explore our partner site’s Our Focus section.

Discussion

Do you think it’s more likely we’ll first find a technosignature (like pollution) or a deliberate communication? Should we be more cautious about Active SETI (METI), or is it our responsibility as a curious species to announce our presence? If an AI made a confident detection but no human could interpret the signal, would you consider it a “discovery”? Share your thoughts on the search, its meaning, and its methods below.