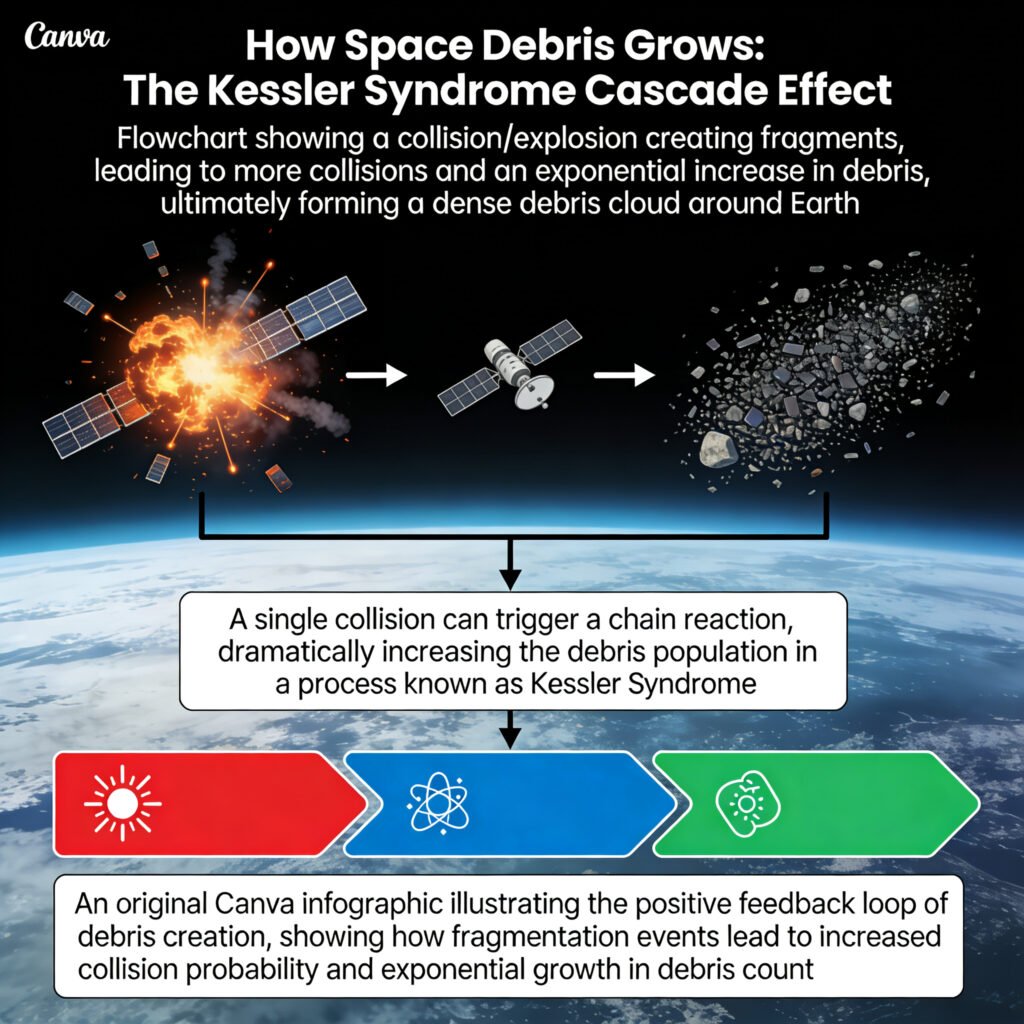

A single collision can trigger a chain reaction, dramatically increasing the debris population in a process known as Kessler Syndrome.

Introduction – Why This Matters

I was reviewing data from a satellite operator client in 2023 when I saw it: a “red alert” conjunction warning. Their $250 million telecommunications satellite was projected to pass within 120 meters of a defunct Soviet-era rocket body. The probability of collision was 1 in 750—well above the threshold for action. For 48 tense hours, a team of engineers worked around the clock, analyzing conflicting data from different tracking networks. They finally performed an avoidance maneuver, burning precious fuel and slightly shortening the satellite’s operational life. The cost? Over $250,000 in labor and lost service. The culprit? A piece of space junk that no one owns or controls. This isn’t a rare event; it’s the new normal in Earth’s congested orbits.

For curious beginners, space debris might sound like a distant sci-fi problem. For professionals in aerospace, it’s a daily operational headache and a looming existential threat. What I’ve learned from astrodynamicists and space lawyers is this: Space debris is the ultimate tragedy of the commons, and we are perilously close to a tipping point. In 2025, with over 11,000 active satellites and an estimated 130 million pieces of debris larger than 1 mm, our ability to use space for communication, navigation, weather forecasting, and science is at risk. This article will explore how AI, new sensors, and innovative robotics are being deployed in a high-stakes cleanup race to prevent a cascade of collisions that could render vital orbits unusable for generations.

Background / Context: From Sputnik to the Orbital Junkyard

The space age began with a single satellite (Sputnik, 1957) and pristine orbits. It has since become a story of accumulation. Every launch leaves spent rocket stages. Every mission can create debris through explosions (intentional or accidental), collisions, or simple deterioration.

The debris population grows through a vicious cycle:

- Fragmentation Events: A collision or explosion creates thousands of new debris pieces.

- Increased Collision Risk: More debris increases the probability of future collisions.

- Cascade Effect: Each new collision creates more debris, further increasing risk—a scenario termed “Kessler Syndrome” after NASA scientist Donald Kessler, who hypothesized it in 1978.

Key events turned theory into urgent reality:

- 2007: China’s anti-satellite (ASAT) test on its Fengyun-1C satellite created over 3,500 trackable fragments, the single worst debris-creating event in history.

- 2009: The first major accidental collision between an active U.S. Iridium satellite and a defunct Russian Cosmos satellite generated another 2,000+ trackable pieces.

- 2021: Russia’s ASAT test on Cosmos 1408 created a debris field that threatened the International Space Station, forcing astronauts to take shelter in escape capsules.

We are now in a regime where, in certain orbits like Low Earth Orbit (LEO), debris-on-debris collisions are becoming the dominant source of new fragments. We are no longer just polluting space; we are triggering a slow-motion chain reaction.

Key Concepts Defined

- Space Debris (Orbital Debris): Any human-made object in Earth orbit that no longer serves a useful function. This includes defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, fragmentation debris, and even flakes of paint.

- Kessler Syndrome: A theoretical scenario where the density of objects in LEO is high enough that collisions between objects cause a cascade, each collision generating debris that increases the likelihood of further collisions, potentially rendering certain orbital regions unusable.

- Conjunction Assessment: The process of analyzing the close approach (conjunction) of two orbiting objects to determine collision risk. Performed by organizations like the U.S. Space Force’s 18th Space Defense Squadron (18 SDS).

- Active Debris Removal (ADR): The use of a dedicated spacecraft to rendezvous with, capture, and deorbit a large debris object, speeding up its natural atmospheric decay.

- Space Traffic Management (STM): The set of technical and regulatory practices for coordinating space operations to minimize collision risk, akin to air traffic control for space.

- On-Orbit Servicing (OOS): The capability to rendezvous with a satellite to inspect, refuel, repair, or upgrade it. The same technology can be used for ADR.

- CubeSat: A miniature, standardized satellite, often deployed in large constellations. Their proliferation is a major new factor in orbital congestion.

- Post-Mission Disposal (PMD): A set of guidelines (like the 25-year rule) requiring satellite operators to deorbit their satellites within 25 years of mission end to limit long-term debris.

How It Works: The Four-Pillar Strategy for Orbital Sustainability

Managing space debris is a multi-front war requiring detection, prevention, mitigation, and active removal. Here’s how each pillar works.

Pillar 1: Space Domain Awareness (SDA) – The Tracking Network

You can’t manage what you can’t see. The foundation is a global sensor network.

- Ground-Based Radar: The workhorse. Powerful radars like the U.S. Space Surveillance Network (SSN) can track objects as small as ~5 cm in LEO. They measure range, angle, and velocity.

- Ground-Based Optical Telescopes: Used for higher orbits (Geostationary, GEO) where radar is less effective. They detect sunlight reflecting off objects.

- Space-Based Sensors: The next frontier. Satellites equipped with optical sensors can track debris from orbit, providing a different vantage point and tracking objects that ground sensors might miss.

- The Data Fusion Challenge: Data from dozens of global sensors comes in different formats and qualities. The first job is correlation—determining if two sensor reports are the same object. This is where Machine Learning (ML) is revolutionizing the field. AI algorithms can correlate tracks faster and more accurately than humans, especially for the ever-growing “catalog” of objects (over 45,000 tracked as of 2025).

Pillar 2: Collision Avoidance – The Daily Dance

This is the operational front line for satellite operators.

- Data Feed: Operators subscribe to conjunction data warnings from the 18 SDS or commercial services like LeoLabs or Privateer Space.

- Risk Assessment: An automated system ingests the warning, which includes:

- Time of Closest Approach (TCA)

- Miss Distance

- Probability of Collision (Pc) – The critical metric. A Pc of 1 in 10,000 (10⁻⁴) often triggers analysis; 1 in 1,000 (10⁻³) usually triggers planning for a maneuver.

- AI-Powered Decision Support: This is where it gets complex. A maneuver costs fuel (shortening satellite life) and takes the satellite offline. AI tools now model:

- Uncertainty Visualization: Showing the “pizza box” of possible positions for each object at TCA.

- Maneuver Optimization: Calculating the smallest, most fuel-efficient burn that achieves a safe miss distance.

- Cascade Risk: Modeling how a maneuver might affect future conjunctions with other objects.

- *A European Space Agency operator told me: “Five years ago, we’d get 10 high-interest alerts a week. Now, with megaconstellations, it’s 100. Without AI triage, we’d be paralyzed.”*

- Execution: If a maneuver is ordered, the satellite fires its thrusters, changing its orbit slightly. All parties are notified to update their own risk assessments.

Pillar 3: Mitigation – Designing for a Clean Exit

Preventing new debris is cheaper than cleaning it up.

- Design Standards: Satellites are now built with:

- Passivation: Venting leftover fuel and discharging batteries at end-of-life to prevent explosions.

- Durable Materials: Using less fragment-prone components.

- Deorbit Systems: Including drag sails, electrodynamic tethers, or dedicated propulsion to ensure compliance with the 25-year rule.

- The “25-Year Rule”: A widely adopted but increasingly criticized guideline. In congested LEO, many argue it should be reduced to 5 years or less. New regulations in the EU and U.S. are pushing for this.

Pillar 4: Active Debris Removal (ADR) – The Cleanup Missions

This is the most technologically challenging and expensive pillar—the actual “garbage truck” of space.

Step-by-Step of a Robotic ADR Mission:

- Target Selection: Choose a high-risk, high-mass object (e.g., an old rocket body). Mass matters because it has more “negative space weather”—its drag helps deorbit smaller debris after capture.

- Rendezvous & Proximity Operations: The ADR spacecraft uses precise navigation to approach the tumbling, non-cooperative target. Computer vision and LiDAR map the target’s motion and shape in real-time.

- Capture: This is the critical technological hurdle. Multiple concepts are in testing:

- Robotic Arm: Like the one on the ISS, but autonomous. Effective for satellites with a standardized interface.

- Net: A deployable net that entangles the target. Good for irregular, tumbling objects. Tested by missions like RemoveDEBRIS.

- Harpoon: Fires a tethered harpoon into the target’s body (tested by RemoveDEBRIS).

- Tentacles/Claws: Compliant mechanisms that wrap around the target.

- Ionic Electrospray: A newer concept using a directed stream of charged particles to “push” debris without physical contact.

- Deorbit: Once captured, the ADR spacecraft fires its engine to lower both itself and the target’s orbit, ensuring a controlled or uncontrolled re-entry over a remote ocean area.

Comparison of Leading ADR Capture Technologies

| Technology | Advantages | Challenges | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic Arm | Precise, can handle standardized interfaces | Requires stable or predictable target; complex | Operational for cooperative targets (Northrop Grumman MEV) |

| Net | Can capture irregular, tumbling objects | Risk of entanglement; deployment complexity | Demonstrated in orbit (RemoveDEBRIS) |

| Harpoon | Simple, can penetrate dense structures | Creates small secondary debris; requires a solid target | Demonstrated in orbit (RemoveDEBRIS) |

| Ionic Electrospray | No physical contact, no risk of break-up | Very low thrust, only suitable for small debris | Lab/early prototype |

Why It’s Important: Protecting a Trillion-Dollar Domain

The space economy is projected to exceed $1 trillion by 2040. Space debris threatens this entire enterprise:

- Critical Infrastructure at Risk: GPS for navigation, satellite comms for finance and media, weather satellites for disaster prediction, Earth observation for agriculture and climate science—all rely on clear orbits. A major collision in a key orbital shell could disrupt global systems overnight.

- Economic Cost of Avoidance: As mentioned in my opening anecdote, collision avoidance is already a multi-million dollar annual cost for operators. This cost is passed on to consumers and taxpayers.

- Blocking Future Access: A full-blown Kessler Syndrome event in LEO could make it too risky to launch through the debris cloud to reach higher, cleaner orbits like GEO. We could be trapped on Earth by our own garbage.

- National Security: Space is a vital domain for defense. Debris threatens reconnaissance, communication, and early-warning satellites. Furthermore, the ability to remove debris is “dual-use” technology—the same spacecraft could be used to inspect or disable an adversary’s satellite, raising complex global affairs and political questions.

- The Moral Imperative: As Dr. Moriba Jah, a leading astrodynamicist, often states: “We are the first generation with the power to permanently alter the orbital environment. We have a responsibility to be its stewards, not its vandals.”

Sustainability in the Future: The Autonomous Orbital Ecosystem

The future of space sustainability lies in an integrated, automated system:

- The “Internet of Space Things”: Satellites will be equipped with low-power transponders that broadcast their identity and precise position, eliminating tracking uncertainty. This is a move from “soda can in the sky” to “smart car on the orbital highway.”

- AI-Driven Autonomous Traffic Management: Instead of thousands of separate conjunction analyses, a shared space traffic coordination system will use AI to compute optimal “right-of-way” for all active satellites simultaneously, suggesting coordinated maneuvers that minimize total fuel burn for the constellation.

- On-Orbit Recycling and Refueling: Instead of deorbiting valuable satellites, servicing vehicles will refuel, repair, or upgrade them, extending life and reducing new launches. At end-of-life, the servicer might harvest valuable components before performing the deorbit, a concept explored in our partner site’s articles on innovative business models.

- “Just-in-Time” Collision Avoidance: With ultra-precise tracking and trust in automated systems, satellites will execute last-minute, tiny avoidance maneuvers, minimizing service disruption.

- Large-Scale ADR Constellations: Swarms of small, inexpensive ADR spacecraft, powered by AI for target recognition and capture, will systematically remove the most dangerous derelict objects. Think “Roomba for LEO.”

Common Misconceptions

- Misconception: “Debris will just burn up in the atmosphere.” Reality: This is only true for objects in very low orbits (below ~600 km). Objects above 800 km can remain for centuries. The most congested and valuable orbits for constellations (1,000-1,200 km) have natural decay times measured in millennia.

- Misconception: “We can just blast debris with lasers from the ground.” Reality: Ground-based lasers lack the power to vaporize debris. However, they could be used for “laser ablation” or “light nudging”—gently pushing on debris with a laser to slightly alter its orbit and avoid a collision, or to speed up its atmospheric decay. This is a promising but non-destructive mitigation concept.

- Misconception: “It’s a problem for the future.” Reality: It is a problem for right now. The number of avoidance maneuvers is increasing exponentially. The 2025 ESA Annual Space Environment Report states that the number of fragmentation events per year has been steadily rising, and the long-term stability of LEO is already compromised.

- Misconception: “Private companies launching constellations are the only problem.” Reality: While megaconstellations add many new objects, the greatest collision risk comes from the legacy debris—thousands of old rocket bodies and defunct satellites from the 70s, 80s, and 90s, primarily from government programs. Solving the problem requires addressing this historical legacy.

Recent Developments (2024-2025)

- First Commercial ADR Contract Awarded: In late 2024, the European Space Agency (ESA) awarded a €75 million contract to the ClearSpace-1 consortium to perform the first active removal of a specific, large debris object (a Vespa upper stage adapter) in 2027. This is a watershed moment for commercial ADR.

- ASTRIAGraph Goes Mainstream: Dr. Moriba Jah’s open-source, AI-powered space traffic visualization tool, ASTRIAGraph, has been adopted by several national agencies and companies as a unified situational awareness platform, integrating over 400 data sources.

- The “Orbital Reef” Incident: In early 2025, a debris fragment (likely from the 2009 Iridium-Cosmos collision) struck a commercial space station module under development, causing minor but costly damage and delaying the program. This tangible economic loss galvanized new industry investment in debris shielding and tracking.

- U.S. Space Force “Tactically Responsive Space” Demo: The Victus Nox mission in 2024 demonstrated the ability to launch a satellite on 24-hour notice. While a military mission, the underlying rapid tasking, launch, and orbit insertion technology is directly applicable to quickly deploying debris inspection or removal assets.

- FCC’s 5-Year Deorbit Rule: The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) made headlines in 2024 by formally adopting a 5-year post-mission disposal rule for U.S.-licensed satellites, putting regulatory teeth behind the push for faster cleanup.

Success Story: The RemoveDEBRIS Mission (2018-2019)

While not a full-scale removal, the UK-led RemoveDEBRIS mission (deployed from the ISS) was a resounding success as a technology demonstrator. It tested three key ADR technologies in orbit:

- Net Capture: It deployed a small cubesat target and then successfully captured it with a net.

- Harpoon Capture: It deployed a target panel and successfully harpooned it.

- Drag Sail: It deployed a large sail to dramatically increase atmospheric drag, accelerating its own deorbit from years to months.

The mission proved that complex capture mechanisms could work in microgravity. More importantly, it provided invaluable engineering data on the dynamics of net deployment, harpoon impact, and target motion. This real-world data is now feeding into the design of the commercial ClearSpace-1 mission. RemoveDEBRIS showed that international university and industry consortia could execute low-cost, high-impact technology validation, paving the way for the commercial ADR sector we see emerging today.

Real-Life Examples

- For a Mega-Constellation Operator (e.g., Starlink, OneWeb):

- Uses an internal, AI-powered collision avoidance system that ingests data from the 18 SDS and commercial trackers.

- Each satellite has autonomous propulsion (ion thrusters) and can execute avoidance maneuvers automatically if ground communication is lost.

- Designs satellites for 100% reliability in post-mission disposal, with built-in propulsion to deorbit within months of failure.

- For the International Space Station (ISS):

- Monitored 24/7 for conjunction risks. In 2023, it performed two pre-planned debris avoidance maneuvers.

- Equipped with Whipple Shields—layered outer walls that cause impacting small debris to vaporize before penetrating the pressurized hull.

- Serves as a testbed for debris inspection cameras and proximity operations technology.

- For a National Space Agency (e.g., JAXA, Japan):

- Developing the CRD2 (Commercial Removal of Debris Demonstration) project with partner Astroscale, focusing on capturing a discarded Japanese upper stage rocket body using a magnetic docking plate—a technology that could also be used for future satellite servicing.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Space debris is a classic “wicked problem”: technically complex, economically challenging, and mired in geopolitical sensitivities. There is no single solution. Success requires a synchronized push on all four fronts: better tracking, stricter rules, smarter satellites, and active cleanup.

The window to act decisively is still open, but it is narrowing. The next decade will determine whether we manage the orbital environment or become its victims. The technologies—AI for tracking and traffic management, robotics for capture—are advancing rapidly. What’s needed now is the collective will, international cooperation, and sustainable business models to deploy them at scale.

We have a choice: we can leave a legacy of innovation and stewardship, or a legacy of irreparable clutter. The clean-up has begun, but the real race is against the exponential logic of the Kessler Cascade.

Key Takeaways Box:

- Debris is an Immediate, Economic Threat: It’s not a distant issue; it costs operators millions now and risks trillions in future economic activity.

- Tracking is the First Step: You can’t avoid or remove what you can’t see. AI is revolutionizing our ability to catalog and predict the paths of millions of objects.

- Prevention is Cheaper than Cure: Designing satellites for easy disposal is the most cost-effective solution. Regulations must enforce this.

- Active Removal is Technologically Feasible: Missions like RemoveDEBRIS have proven the core capture technologies. The challenge is scaling and funding.

- International Cooperation is Non-Negotiable: Space has no borders. Effective governance requires data sharing and agreed-upon rules of the road, a topic perpetually in the news (see Breaking News for latest developments).

For more clear explanations of complex scientific and technological challenges, explore our full library at The Daily Explainer.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How big does debris have to be to be dangerous?

It depends on speed. In LEO, objects travel at about 7.5 km/s (17,000 mph). At that speed:

- A 1 cm paint fleck has the kinetic energy of a bowling ball thrown at 60 mph—enough to disable a satellite.

- A 10 cm object (a spanner) is catastrophic—it would likely destroy any satellite or crewed vehicle it hits.

2. Who is responsible for cleaning up space junk?

Legally, it’s murky. The Outer Space Treaty says states are liable for objects they launch. But there’s no law forcing them to clean up defunct objects. Practically, the entities creating the new risk (constellation operators) and those with the most to lose (all spacefaring nations) are driving the development of solutions. The “polluter pays” principle is being discussed but not codified.

3. Can’t we just move the ISS to avoid debris?

Yes, and they do. The ISS has performed over 30 debris avoidance maneuvers in its lifetime. However, each maneuver uses propellant that must be resupplied by cargo missions. It’s a costly and temporary fix.

4. How many pieces of space debris are there?

- Trackable (>10 cm): ~45,000 objects (cataloged by the U.S. Space Force).

- Lethal Non-trackable (1 cm to 10 cm): ~1,000,000 objects.

- Damaging (>1 mm): ~130,000,000 objects.

5. What happens when debris re-enters the atmosphere?

Most burns up due to intense heat from atmospheric friction. Larger, denser objects (like rocket cores) can survive. Re-entries are carefully tracked to predict the “debris footprint,” which is usually over an uninhabited ocean area. The risk to individuals on the ground is extremely low.

6. Are there any laws about creating space debris?

Very few with teeth. The UN has Long-Term Sustainability (LTS) Guidelines, but they are voluntary. National regulations (like the FCC’s 5-year rule) are becoming the primary enforcement mechanism. A major international treaty is needed but politically difficult.

7. How do you track something as small as 1 cm?

You generally can’t consistently track it from the ground. That’s why the number is an estimate based on statistical models from radar returns and examination of surfaces returned from space (like the Space Shuttle windows, which were often pitted by tiny impacts).

8. What is the most congested orbit?

Sun-Synchronous Orbit (SSO) around 700-900 km is extremely congested due to its popularity for Earth observation satellites. The region from 900-1,200 km is now seeing massive congestion from communications constellations like Starlink and OneWeb.

9. Could debris prevent us from leaving Earth?

Potentially, yes. A severe Kessler Syndrome cascade in LEO could create a lethal shell of shrapnel. Launching through it would require heavy shielding (increasing cost) or finding very narrow “clean” lanes. It would make space access far more dangerous and expensive, not impossible.

10. What is a “debris conjunction screening” service?

Companies like LeoLabs and COMSPOC offer enhanced tracking data and conjunction warnings beyond what governments provide. They use their own radar networks and advanced algorithms to offer higher-fidelity data, shorter update times, and tracking of smaller objects for a subscription fee.

11. How does AI improve conjunction predictions?

Traditional methods treat uncertainty as a simple “pizza box.” Machine Learning can analyze historical tracking errors, object characteristics (size, shape, material), and space weather data to create a more accurate, non-linear probability “cloud” for where an object truly might be, drastically reducing false alarms.

12. What is an “electrodynamic tether” for deorbiting?

A long, conductive tether deployed from a satellite. It interacts with Earth’s magnetic field, generating a Lorentz force that acts as drag, pulling the satellite down. It’s a passive, propellant-free deorbit method being tested on several cubesats.

13. Is it legal to remove another country’s debris?

Another legal gray area. Touching another state’s object could be seen as a violation of sovereignty. Most ADR missions plan to target “ownerless” objects or work under contract with the launching state. ClearSpace-1, for example, is removing an ESA-owned adapter with ESA’s permission.

14. Could we recycle space junk?

In the far future, perhaps. Concepts exist for orbital “foundries” that would melt down aluminum from old rocket bodies to use as raw material for 3D printing new structures in space. This is far beyond current technology but aligns with principles of a circular economy, similar to those discussed in our partner’s Nonprofit Hub focusing on sustainable systems.

15. How does space weather affect debris?

Solar activity matters a lot. A active sun heats and expands the upper atmosphere, increasing drag on objects in LEO and speeding up natural decay. During solar maximums, more debris falls naturally. During solar minimums, debris persists longer. This must be factored into long-term models.

16. What can an individual do about space debris?

Support policies and companies committed to sustainability. As a consumer, you can choose internet/TV providers that partner with responsible satellite operators. Educate others. The problem seems vast, but public pressure influences regulators and investors.

17. Have any satellites been destroyed by debris?

Not yet catastrophically, but there have been non-fatal impacts. In 2021, a debris fragment struck the Copernicus Sentinel-1A solar array, causing a small power loss and a minor change in the satellite’s orbit and attitude. It was a warning shot.

18. What is “just-in-time collision avoidance”?

A future concept where, with ultra-precise real-time tracking, a satellite could wait until the last safe moment to execute a tiny, minimally disruptive avoidance maneuver, rather than making a larger, disruptive maneuver hours in advance.

19. How do you capture a tumbling object?

This is a major robotics challenge. The servicer spacecraft must first match the tumble (a complex maneuver), or more commonly, use a compliant capture system (like a net or tentacles) that can handle the relative motion. Advanced computer vision is used to predict the tumbling motion in real-time.

20. Is there an “orbit police”?

Not really. The UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) promotes guidelines. The 18th Space Defense Squadron provides data but doesn’t issue commands. True “space traffic control” with authority to mandate maneuvers does not exist—it’s a major gap in the current system.

21. How does the mental model of tackling space debris compare to starting a complex project on Earth?

The parallels are striking. It requires: Assessing the Scope (tracking the problem), Preventing New Issues (mitigation design), Building a Skilled Team (international consortia), Developing New Tools (ADR tech), and Creating a Sustainable Business Model (who pays?). It’s a massive, multi-stakeholder project management challenge, not unlike launching a groundbreaking new venture, a process detailed in resources like Sherakat Network’s startup guide.

22. What is the “25-year rule” and why is it criticized?

It’s a guideline that satellites in LEO should deorbit within 25 years of mission end. Critics say it’s too long—it allows dead satellites to linger in crowded orbits for decades, accumulating risk. The new push is for 5 years or less, especially for large constellations.

23. Where can I see real-time space debris tracking?

Several public websites offer visualizations:

- Stuff in Space (stuffin.space): A real-time 3D map of tracked objects.

- ESA’s Space Debris User Portal (sdup.esoc.esa.int): Provides data and visualizations.

- ASTRIAGraph (astria.tacc.utexas.edu): Dr. Jah’s advanced, multi-source visualization tool.

About the Author

Sana Ullah Kakar is a space policy analyst and former aerospace systems engineer. They spent the early part of their career working on satellite collision risk assessment software, giving them a front-row seat to the worsening debris problem. Frustrated by the gap between technical understanding and policy action, they shifted to communications and analysis, working with operators, insurers, and governments to translate risk into actionable strategy. At The Daily Explainer, they believe that an informed public is the most powerful catalyst for responsible space stewardship. They see the debris challenge not as a doom-laden prophecy, but as a solvable engineering and governance puzzle—one of the greatest tests of our generation’s ability to cooperate on a global scale. When not analyzing orbital data, they are an avid rock climber, finding a strange peace in solving complex physical puzzles on a cliff face. For more, or to discuss these issues, visit our contact page.

Free Resources

- ESA’s Space Debris Office: The most comprehensive public resource, with annual reports, technical documents, and educational materials.

- NASA Orbital Debris Program Office: Technical reports, measurement data, and the definitive “Orbital Debris Quarterly News.”

- UNOOSA Space Debris Resources: The international policy perspective, including the UN LTS Guidelines.

- The Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy: Excellent, readable reports on the economic and policy dimensions of space sustainability.

- Visualization Tools: Explore Stuff in Space and ASTRIAGraph to see the problem firsthand.

- Related Reading on Systemic Challenges: For insights into managing other complex global systems, explore articles on global supply chains and more in our blog.

Discussion

Do you think the primary driver for cleaning up space debris will be government regulation, economic pressure on operators, or public outcry? Which ADR technology seems most promising to you? Should we focus on removing a few large rocket bodies or many smaller fragments? Share your perspective on the orbital cleanup challenge below.