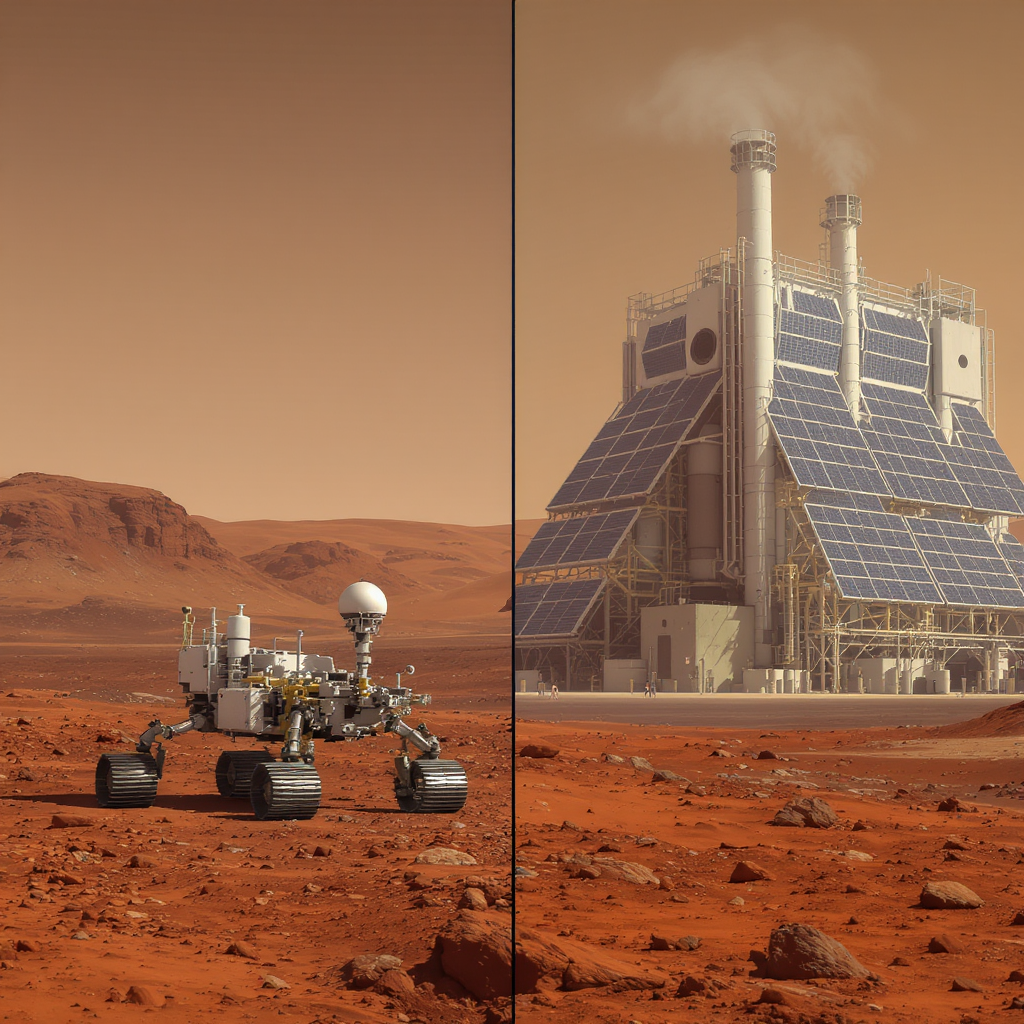

NASA's MOXIE experiment (left) was a critical proof-of-concept. A future human mission will require a plant hundreds of times larger (right).

Introduction – Why This Matters

I remember the exact weight: 1.1 kilograms. That’s the mass of the tiny vial of “synthetic regolith” – fake moon dust – a NASA engineer handed me during a workshop a few years ago. “This,” he said, “cost about $100,000 to get to the Moon in our current model. A single liter of water there? Over $1 million.” That moment wasn’t just about cost; it was about the fundamental barrier to a sustainable human presence in space. We cannot afford to be interplanetary pack mules, hauling every drop of water, every brick, and every breath of air from the bottom of Earth’s deep gravity well.

This is why In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) is the most critical, yet under-discussed, technological leap for the future of space exploration. For curious beginners, ISRU is the ultimate form of cosmic recycling. For professionals, it’s the grand engineering challenge that separates flags-and-footprints missions from permanent settlements. What I’ve found, through conversations with mission architects and resource scientists, is that ISRU isn’t a single gadget; it’s an entire off-world industrial ecosystem that must be largely autonomous, incredibly reliable, and bootstrapped with minimal initial supplies. In 2025, with the Artemis program targeting a sustained lunar presence and SpaceX aiming for Mars, ISRU has moved from science fiction to urgent, funded engineering. This article will unpack how we’ll use AI, robotics, and chemistry to transform alien dirt into lifeblood.

Background / Context: The Tyranny of the Rocket Equation

The Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky laid down the law in 1903: the rocket equation. It states that the velocity change (Δv) a rocket can achieve depends on the exhaust velocity and, crucially, the ratio of its initial mass to its final mass. Every kilogram you want to land on Mars requires launching exponentially more kilograms from Earth due to the fuel needed to escape Earth, transit, and land.

The numbers are brutal. To land 1 metric ton of supplies on Mars, you might need to launch 200-300 tons from Earth. Sending all the water, oxygen, building materials, and fuel for a multi-year Mars mission for a crew of four could require launching a mass equivalent to an aircraft carrier. It’s economically and practically impossible.

Thus, the paradigm shift: Don’t bring it with you; make it there. This philosophy has ancient roots—explorers and settlers have always sought local water, timber, and stone. But doing this on another world, where the “resources” are toxic dust, trace ice, and a thin, unbreathable atmosphere, is a challenge of a different magnitude. ISRU turns the hostile environment from a pure liability into a potential asset.

Key Concepts Defined

- In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): The collection, processing, storing, and use of materials encountered in the course of human or robotic space exploration to replace materials that would otherwise be brought from Earth.

- Regolith: The layer of loose, heterogeneous superficial dust, soil, and broken rock that covers solid rock on airless bodies like the Moon, asteroids, and some planets. It is the “raw ore” for many ISRU processes.

- Reduced Gravity Processing: The engineering challenge of designing industrial equipment that works in low-gravity (Moon: 1/6g, Mars: 3/8g) or microgravity, where settling, fluid dynamics, and heat transfer behave differently.

- Thermal Mining: A method of extracting volatile resources (like water ice) by applying heat to the regolith, causing the ice to sublimate (turn directly from solid to gas), which is then captured.

- Sabatier Reaction: A key chemical process for Mars. It combines carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the Martian atmosphere with hydrogen (H₂, potentially brought from Earth or derived from water) to produce methane (CH₄, rocket fuel) and water (H₂O).

- Additive Manufacturing in Space (3D Printing): Using regolith or processed materials as feedstock to print structures, tools, and parts on-demand, eliminating the need to ship pre-manufactured items.

- Autonomous Robotic Swarms: Teams of small, cooperating robots that can perform ISRU tasks (excavation, sorting, transport) without constant human guidance, essential for pre-deploying infrastructure before crew arrival.

How It Works: The Step-by-Step Bootstrapping of an Off-World Outpost

Let’s walk through a realistic scenario for establishing a lunar base, highlighting the technology at each stage.

Phase 0: Prospecting & Mapping (The AI-Geologist)

Before you dig, you need to know where to dig. This is where orbital and robotic scouts come in.

- Orbital Reconnaissance: Satellites like NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and India’s Chandrayaan-2 use instruments like:

- Neutron Spectrometers: Detect hydrogen signatures, indicating likely water ice deposits in permanently shadowed craters at the poles.

- Mini-RF Radar: Maps subsurface ice and characterizes regolith properties.

- Surface Robotic Prospectors: Rovers like NASA’s upcoming VIPER (Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover) (scheduled for late 2026) will ground-truth orbital data.

- How VIPER Works: It will drive into shadowed craters, use a drill to sample soil up to 1 meter deep, and analyze the samples with its onboard Mass Spectrometer to quantify water and other volatiles. Its AI-driven navigation will allow it to operate in the darkness of the polar regions and avoid hazards autonomously.

- “The AI isn’t just driving,” a VIPER engineer told me. “It’s deciding in real-time where the most scientifically valuable—and resource-rich—next drilling location is, based on the composition of the last sample.”

Phase 1: Extraction & Collection (The Robotic Miner)

Once a high-value site is identified, mining begins. Human presence is risky, so robots do the heavy lifting first.

- Excavation: Regolith is abrasive and sticky (due to static charge). Bulldozer-like blades or bucket drums made from specialized materials are used. In low gravity, excavation forces are different; a robot can lift heavier loads but must be designed to not launch itself with each scoop.

- Thermal Mining for Ice: For water ice locked in regolith, a thermal mining probe is inserted. It heats the surrounding regolith to 150-200°C. The ice sublimates into water vapor, which travels up the probe to a cold trap where it re-condenses as frost or liquid. This is far more energy-efficient than digging and hauling tons of icy dirt.

Phase 2: Processing & Refinement (The Micro-Factory)

Raw regolith or captured vapor isn’t useful. It must be processed.

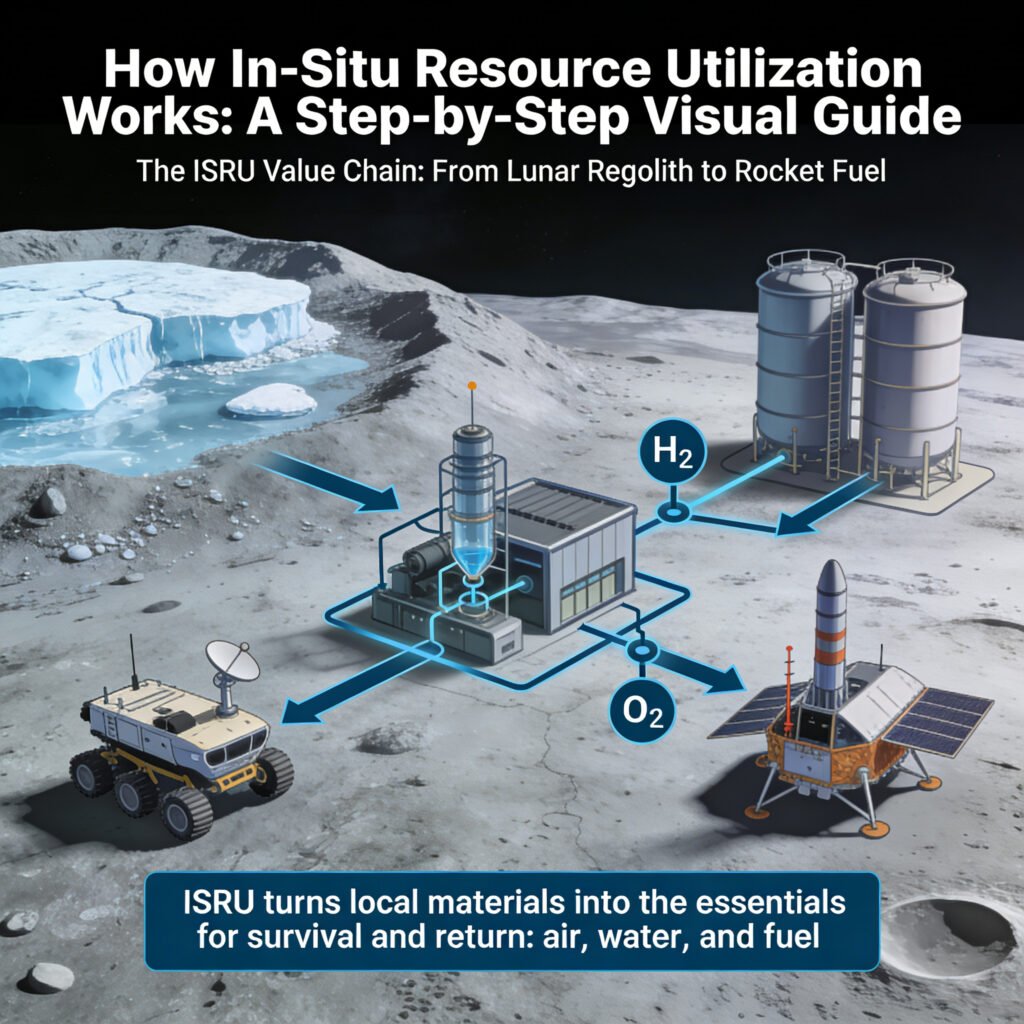

- Water Purification: Sublimated water vapor is contaminated with other volatiles (ammonia, methane). Multi-stage filtration and distillation, powered by solar energy, produce potable water for drinking and splitting into oxygen/hydrogen.

- Regolith to Oxygen:

- Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE): Heats lunar regolith to over 1600°C, melting it. An electric current is passed through the molten material, causing oxygen to bubble out at the anode. The byproduct is molten metal alloys (iron, silicon, aluminum) useful for construction. Companies like Lunar Resources are prototyping this.

- Carbothermal Reduction: Uses methane or carbon to react with metal oxides in the regolith, producing carbon monoxide and metal.

- Atmospheric Processing on Mars (MOXIE – Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment):

- NASA’s MOXIE, aboard the Perseverance rover, has already proven the concept. It works like a fuel cell in reverse:

- Intake: Pulls in thin Martian air (96% CO₂).

- Compression: Pressurizes the CO₂.

- SOXE (Solid Oxide Electrolysis): Heats the CO₂ to 800°C and uses an electrochemical cell to split it into carbon monoxide (CO) and oxygen ions. The ions combine to form pure O₂ gas.

- Output: Vents the CO and stores the O₂. MOXIE produced 122 grams of oxygen per hour in tests—about what a small dog breathes. A scaled-up system for a human mission would need to be 200 times larger.

- NASA’s MOXIE, aboard the Perseverance rover, has already proven the concept. It works like a fuel cell in reverse:

Phase 3: Utilization & Manufacturing (The On-Site Workshop)

Now you have usable materials. What do you do with them?

- Life Support: Oxygen goes into habitat tanks. Water is used for drinking, hygiene, and growing food in hydroponic systems.

- Propellant Production: This is the biggest mass saver. On the Moon:

- Split water (H₂O) via electrolysis into Liquid Oxygen (LOX) and Liquid Hydrogen (LH₂)—the fuel for many rockets.

- Or, use the hydrogen to reduce ilmenite (FeTiO₃, common in lunar maria) to produce water and oxygen, with iron as a byproduct.

- On Mars, the Sabatier Reaction is king for making methane (CH₄) fuel.

- Additive Construction: Regolith 3D Printing uses sunlight or lasers to sinter (fuse) regolith grains into a ceramic-like solid. The D-Shape printer and NASA’s Olympus project are testing this to print landing pads, radiation shields, roads, and entire habitats layer by layer. This solves the “bring your own house” problem.

- Fabrication of Spare Parts: Rather than bringing a spare for every possible broken part, bring a 3D printer filament made from processed polymers or metallic regolith dust. A broken bracket can be designed on a computer and printed overnight.

ISRU Technology Flowchart: From Regolith to Refuge

(Conceptual Canva Graphic Description)

A flowchart showing: Prospecting (Orbiters/Rovers) → Mining (Excavators/Thermal Probes) → Processing (MRE, MOXIE, Purification) → Outputs: O₂, H₂O, CH₄, Metals → Utilization: Life Support, Fuel, 3D Printed Structures.

Why It’s Important: The Gateway to a Sustainable Spacefaring Future

ISRU is not just a technical curiosity; it’s the foundational capability for three transformative outcomes:

- Radical Reduction in Mission Cost and Risk: By producing fuel for the return journey on Mars, you cut the initial launch mass from Earth by more than half. This makes missions more affordable and frequent. It also provides a critical safety margin—if you can make air and water, you have a buffer against life support failures.

- Enabling Long-Duration Presence and Settlement: You cannot sustain a lunar base for months or years with only what you brought. ISRU creates a closed-loop or semi-closed-loop ecosystem, moving from “camping” to “homesteading.” As Dr. Gerald Sanders, NASA’s ISRU System Capability Lead, says: “ISRU is the difference between exploration and expansion.”

- Unlocking Economic Activity in Space: This is the long-term vision. Water ice can be split into propellant, creating orbital fuel depots around the Moon or Earth. This could refuel satellites, extending their lives, or fuel deep-space missions, making the Moon a gas station for the solar system. Precious metals from asteroids, while a more distant prospect, represent another economic driver. This nascent economy will require new frameworks, much like the legal and partnership structures discussed in resources on global affairs and politics.

Sustainability in the Future: The Self-Growing Habitat

Looking to the 2040s and beyond, ISRU evolves from making supplies to growing infrastructure.

- Autonomous Self-Replication: The ultimate goal is a suite of machines that can use local resources not just to support humans, but to reproduce themselves. A robotic factory that mines regolith, extracts metals, and 3D prints the parts for a second, identical factory. This is the key to exponential growth of infrastructure without continuous Earth resupply.

- Biomanufacturing: Introducing engineered microbes or plants that can thrive in controlled, off-world environments to produce plastics, medicines, or food from waste streams and local materials, creating a true bio-regenerative life support system.

- Large-Scale Civil Engineering: Using coordinated swarms of hundreds of robots to construct massive infrastructure—microwave-beaming power stations, shielded lava tube habitats, or even space elevator anchors—using almost entirely local material.

- AI-Optimized Resource Networks: An AI “foreman” will manage the entire outpost’s resource flow, directing robots to mine high-ice regolith because the water electrolyzer is running low, pausing metal printing because a solar storm is coming, and scheduling maintenance based on predictive analytics. This level of systemic AI management is a frontier in itself, akin to advances we track in other explained technology domains.

Common Misconceptions

- Misconception: “ISRU means we’ll be strip-mining the Moon and destroying it.” Reality: The scale of initial ISRU is tiny. A human mission might extract a few hundred tons of regolith per year. The Moon has quintillions of tons. Furthermore, mining would likely focus on already-disturbed areas (like landing sites) or specific mineral-rich zones, with care taken to preserve scientifically valuable areas.

- Misconception: “It’s all about finding gold and becoming space trillionaires.” Reality: The near-term economic driver is volatiles, not precious metals. Water and oxygen are the “oil” of space exploration—bulk commodities with immediate, life-supporting value. Asteroid mining for platinum is a much farther-term prospect with enormous technical and economic hurdles.

- Misconception: “We can just test everything on Earth first.” Reality: While we test components extensively, the combination of low gravity, vacuum, extreme temperatures, and abrasive dust creates a unique environment. That’s why instruments like MOXIE and upcoming lunar missions are so critical—they are the only way to get true “field data.”

- Misconception: “If we can do ISRU, we don’t need to worry about recycling on spacecraft.” Reality: ISRU and recycling are complementary, not exclusive. A habitat will always need highly efficient closed-loop life support (recycling air and water) to minimize the scale of the ISRU plant needed. ISRU handles bulk mass, recycling handles daily efficiency.

Recent Developments (2024-2025)

- MOXIE’s Final Success: Before the Perseverance rover powered down its primary mission in late 2024, MOXIE was run one final time, exceeding its original goals and providing a complete dataset for designing a human-scale oxygen factory, which NASA aims to fly in the late 2030s.

- Lunar Trailblazer Launch: This small NASA orbiter, launched in 2025, is specifically designed to map the form, abundance, and distribution of lunar water at a higher resolution than ever before, directly de-risking ISRU planning for Artemis.

- Private Company Milestones:

- Lunar Resources: Successfully demonstrated continuous molten regolith electrolysis in a Texas vacuum chamber, producing both oxygen and metal alloy.

- ICON’s Project Olympus: Awarded a $60 million NASA contract to test its 3D-printing-from-regolith technology on the Moon, potentially as early as 2027.

- Redwire’s Regolith-Derived Photovoltaic Cells: Showed they can fabricate solar cells using simulated lunar regolith, a huge step toward self-sustaining power.

- China’s ISRU Ambitions: The successful return of the Chang’e 6 sample-return mission from the lunar far side in 2024 included experiments on resource extraction techniques, signaling China’s serious, long-term ISRU strategy.

Success Story: The Mars Perseverance Rover & MOXIE

While not a full-scale ISRU plant, MOXIE is an unqualified success story and a masterclass in incremental technology development. Housed in a box the size of a car battery on the Perseverance rover, it was designed to run for a few hours at a time. Over its operational life, it conducted 16 experimental runs, producing a total of over 130 grams of oxygen—enough for a human to breathe for about 4 hours.

The genius of MOXIE was its focus on proving the core technology in the actual Martian environment. It dealt with real dust, real temperature swings, and the real composition of the atmosphere. The data it sent back answered critical questions: How does the electrolysis cell degrade over time with Martian dust? How efficient is the compressor in the thin air? The MOXIE team didn’t just build a prototype; they built a knowledge prototype. This data is now feeding directly into the design of a scaled-up system 200 times larger, which could support a human mission. It’s a perfect example of the “test early, test often” philosophy that de-riskes grand ambitions.

Real-Life Examples

- The Lunar Polar Outpost (Hypothetical 2030s):

- Before Sunrise: Autonomous rovers guided by AI maps have pre-positioned thermal mining rigs in a shadowed crater.

- Daytime Operation: Solar arrays power the miners, sublimating ice. The vapor is piped to a central processing plant where it’s condensed, purified, and split via electrolysis.

- Output: Liquid oxygen and hydrogen are stored in cryogenic tanks. Some water is sent to the greenhouse. The oxygen is used to refill habitat tanks and, crucially, to fuel the Ascent Vehicle that will take astronauts back to lunar orbit.

- The Mars Fuel Depot (Hypothetical 2040s):

- An unmanned ISRU plant lands two years before the crew.

- It uses large solar fields to power a MOXIE-like system for oxygen and a Sabatier reactor (using hydrogen brought from Earth or derived from small amounts of water ice).

- By the time the crew arrives, tanks are filled with liquid methane and liquid oxygen—the exact propellant mix for their SpaceX Starship or equivalent vehicle to launch back to Earth. The crew’s survival depends on a machine that worked autonomously for years before they ever left home.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

In-Situ Resource Utilization is the quiet revolution at the heart of the new space age. It transforms space exploration from an extractive, expeditionary model—where we visit, take samples, and leave—into a generative, infrastructural model—where we arrive, build, and stay.

The path forward is a spiral of increasing capability: robotic prospectors map resources, pilot plants demonstrate extraction, scaled-up systems support crews, and finally, industrial-scale operations enable commerce. Each step relies on advancing autonomy, robotics, and AI to operate in environments where human oversight is delayed by minutes or months.

The ultimate promise of ISRU is not just survival, but thrival. It’s the key to unlocking a future where humanity is a multi-planet species, not because we can afford to ship everything, but because we learned to make what we need from the cosmos itself.

Key Takeaways Box:

- ISRU Solves the Rocket Equation: It breaks the tyranny of launch mass by making the heaviest supplies (fuel, water, air) at the destination.

- It’s a System, Not a Single Tool: Success requires a integrated chain of prospecting, mining, processing, and manufacturing technologies.

- Autonomy is Non-Negotiable: AI and robotics must run these systems due to communication delays and the need to pre-deploy infrastructure.

- The First “Cash Crop” is Water: Volatiles for life support and propellant are the immediate, high-value targets, not precious metals.

- We Are Already Doing It: MOXIE on Mars proved the core concept. The next decade will see these technologies move from experiments to essential mission infrastructure.

For more deep dives into the technologies shaping our future, explore our curated selection of articles in The Daily Explainer’s blog.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What’s the most valuable resource on the Moon?

Water ice. It provides drinking water, breathable oxygen (via splitting), and rocket fuel (hydrogen and oxygen). Its presence in permanently shadowed craters is the primary reason the Artemis program is targeting the lunar south pole.

2. How do you power an ISRU plant on the Moon or Mars?

Primarily with solar panels. Nuclear power (small fission reactors like NASA’s Kilopower project) is a crucial complementary technology for nights on the Moon (14 Earth-days long) and dust storms on Mars, providing reliable base-load power when sunlight is unavailable.

3. Can we use ISRU to build a space station?

Potentially, yes. For stations in lunar orbit or at Lagrange points, raw materials could be mined from the Moon (which has a much weaker gravity well than Earth) and launched to the construction site using a mass driver (electromagnetic railgun). This would be far cheaper than launching all materials from Earth.

4. What’s the biggest technical challenge for ISRU?

Reliability in an extreme environment. The equipment must operate for years with minimal maintenance in vacuum, abrasive dust, extreme temperature cycles (-170°C to +120°C on the Moon), and reduced gravity. It must be largely self-cleaning and self-repairing.

5. Is asteroid mining part of ISRU?

Yes. Asteroids, particularly carbonaceous chondrites, are rich in water-bearing minerals and metals. They represent a longer-term ISRU target. The technological and economic challenges of rendezvousing with, mining, and returning material from asteroids are significant, but the potential payoff is vast.

6. How does low gravity affect processing?

It changes everything. Dust doesn’t settle, it floats. Liquids don’t flow predictably. In molten regolith electrolysis, bubbles of oxygen don’t rise quickly out of the melt. Engineers use centrifugal forces, vibrations, and clever chamber designs to simulate gravity’s useful effects.

7. Who owns the resources extracted in space?

This is a major legal and political question. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty forbids national appropriation of celestial bodies but is vague on resources. The U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 and similar laws in Luxembourg and the UAE assert that companies own what they extract. An international framework is still evolving, a topic often covered in breaking news on space policy.

8. How close are we to having a functional ISRU system?

We have validated key components (MOXIE for Mars O₂, regolith processing in labs). The next 5-10 years will see the first integrated pilot systems on the Moon (e.g., a small water extraction and electrolysis unit). A full system supporting a human mission is likely a 2030s development.

9. Could ISRU be used to terraform Mars?

In the very, very long term, yes. ISRU technologies that release oxygen and other greenhouse gases (like perfluorocarbons) could, over millennia, be used to thicken Mars’s atmosphere and warm the planet. However, this is a planetary-scale engineering project far beyond our current or near-future capabilities and raises serious ethical questions.

10. What role do startups play in ISRU?

A massive role. Companies like Lunar Resources, ICON, Redwire, Masten (now part of Astrobotic), and ispace are driving innovation with private capital, developing specific technologies faster and often at lower cost than traditional government programs. They are the engine of commercial ISRU.

11. How much water is actually on the Moon?

Estimates vary, but data suggests the permanently shadowed regions at the poles could contain hundreds of millions to billions of metric tons of water ice, mixed with regolith. That’s enough to support a sizable lunar base for centuries.

12. Can you grow plants in lunar or Martian soil?

Raw regolith is terrible for plants—it’s fine, sharp, lacks organic matter, and may contain perchlorates (toxic salts). However, it can be processed (washed, mixed with compost from human waste, and aerated) to create productive soil. Experiments on the International Space Station are already testing this.

13. What is “spiritual ISRU”?

A term sometimes used to describe technologies that aren’t about extracting bulk resources but about using local materials for science and exploration. For example, using regolith to shield a habitat from radiation or to create a makeshift repair patch.

14. How does AI specifically help ISRU?

- Autonomous Navigation: Rovers finding their way to mining sites.

- Computer Vision: Sorting valuable ore rocks from worthless ones.

- Predictive Maintenance: Analyzing sensor data to foresee equipment failures.

- Process Optimization: Adjusting temperatures, pressures, and flow rates in a chemical plant in real-time for maximum yield.

- Swarm Coordination: Directing dozens of mining robots to work together efficiently.

15. What happens if an ISRU plant breaks down on Mars before the crew arrives?

This is a critical mission risk. Mitigation strategies include: sending redundant units, designing for extreme reliability (“fault-tolerant systems”), and ensuring the plant can be repaired by the crew with tools and spares they bring. The crew would also bring a limited emergency supply of fuel/oxygen, making the mission a “hybrid” rather than fully dependent on ISRU from day one.

16. Are there any ISRU experiments on the International Space Station (ISS)?

Yes, the ISS serves as a microgravity testbed. Experiments have included testing 3D printers that work in vacuum, studying how regolith simulant behaves in microgravity, and growing plants in simulated regolith. The ISS is a vital proving ground before lunar or Martian deployment.

17. How does the psychology of relying on ISRU affect crew morale?

Knowing your survival depends on machines you can’t immediately fix if they break is a psychological stressor. Training will involve deep understanding of the systems, simulators for troubleshooting, and designing interfaces that give crews clear visibility and a sense of control over their life support “factory.” This human factor is as crucial as the engineering.

18. Could we use ISRU on Earth?

The principles are already used in terrestrial analog environments like Antarctica and in closed-loop life support research. The extreme engineering for space often leads to spin-offs in efficient resource use, recycling, and remote operations technology on Earth.

19. What’s the environmental impact of lunar mining?

On the airless, sterile Moon, “environmental impact” means disturbing the pristine regolith record, which holds a billion-year history of the solar system. The scientific community advocates for careful zoning—industrial areas versus preserved scientific parks. It’s about stewardship, not conservation in the Earthly sense.

20. Where can I learn more about specific ISRU technologies?

NASA’s ISRU Technical Advisory Group publications, the Lunar and Planetary Institute resources, and the websites of companies mentioned (Lunar Resources, ICON) are great starts. For understanding the entrepreneurial drive behind such innovation, resources on starting an online business share a similar spirit of building new ventures in uncharted territory.

21. How does the mental model for ISRU compare to starting a business in a new market?

The parallels are strong. Both involve: Prospecting (market research), Proving the Core Concept (MVP like MOXIE), Securing Funding (NASA contracts/private investment), Scaling Up (pilots to full production), and Creating an Ecosystem (fuel depots, supply chains). It’s frontier entrepreneurship on a cosmic scale, requiring the kind of strategic thinking outlined in partnership guides like Sherakat Network’s blog.

22. Will ISRU make space travel cheap for everyday people?

Not directly in the short term. Initially, ISRU will reduce costs for government and commercial entities running sustained operations. Over decades, as infrastructure matures and the cost of producing propellant in space drops, it could lower the cost of moving around the solar system, eventually benefiting all space activity.

23. What’s the most surprising potential resource in space?

Helium-3 on the Moon. While not useful for ISRU life support, this isotope is rare on Earth and could be a potent fuel for future fusion reactors. While fusion is not yet a proven power source, the presence of He-3 adds a long-term economic incentive for lunar development.

About the Author

Sana Ullah Kakar is an aerospace technologist and science communicator who has worked on the periphery of space resource planning for over a decade. Their career began in planetary science, analyzing data from orbiters, which gave them a deep appreciation for the environments we seek to utilize. They have since worked with engineers and entrepreneurs translating those scientific insights into practical systems. At The Daily Explainer, they are driven by a simple belief: the grandest futures are built by understanding the granular details today. They see ISRU not as a futuristic fantasy, but as the next logical—and utterly necessary—chapter in human ingenuity. When not writing, they can be found with amateur astronomy groups or volunteering with STEM outreach programs, trying to pass on the spark of exploration. You can reach out with questions or comments via our contact page.

Free Resources

- NASA ISRU Project Website: The hub for NASA’s latest research, publications, and mission updates on resource utilization.

- The Moon as a Resource (Lunar and Planetary Institute): A fantastic, accessible primer on lunar geology and resource potential.

- MOXIE Mission Page (NASA JPL): Detailed information on the experiment that proved oxygen production on Mars.

- Space Resources Professional Society (SRPS): An organization connecting professionals in the field, with public webinars and reports.

- Related Reading on Innovation Ecosystems: Explore how other fields build sustainable systems in our partner site’s section on our focus.

- For the Entrepreneurially Minded: See how principles of bootstrapping and resourcefulness apply on Earth in guides from the Sherakat Network resources.

Discussion

Do you think the focus should be on lunar ISRU first, or should we aim directly for Mars? What ethical considerations most concern you about extracting resources from other worlds? If you could design one ISRU machine, what would it produce and why? Share your thoughts and questions in the comments below.